At the conclusion of Hal Ashby’s remarkable Being There, which celebrates its forty-fifth anniversary this month, comes a scene that has only acquired greater resonance and relevance since it first appeared. At the funeral of the plutocrat Ben Rand (Melvyn Douglas), the US president (Jack Warden) is delivering a heartfelt but somehow trite eulogy. As the pallbearers march away with Rand’s casket, which will be buried in the family mausoleum, talk turns to who should replace the president; the film has already suggested that he is suffering from erectile dysfunction and, wickedly, equates this with his falling popularity ratings.

The figure these influential men light upon is none other than Peter Sellers’s Chauncey Gardiner, an enigmatic figure who has achieved national popularity through his status as Rand’s apparent consigliere and advisor. He has appeared on television to make gnomic remarks about seasons and change that the public seizes upon as examples of great wisdom: “As long as the roots are not severed, all is well. And all will be well in the garden.” The joke is that “Chauncey Gardiner” — a good WASP-y name — is, in fact, literally Chance the gardener, speaking not in political metaphors but botanically. Chance has emerged in public with no knowledge of anything apart from gardening and television, taken up by Rand and his wife Eve (a seldom-better Shirley MacLaine) as a savant; they are convinced that he is a remarkable man.

At the conclusion of the film, Gardiner, unaware of the weight of responsibility that will soon be placed upon him — he seems to be a genuine innocent of sorts, not a grifter — wanders away from the funeral, and in one of the most talked-about endings of any American picture of the Seventies, appears to quite literally walk on water: a moment that Ashby transforms from the allegorical to the literal. As he walks, Gardiner temporarily submerges his umbrella in the lake, suggesting that he does, after all, possess some kind of supernatural ability. Thanks to what may well be Sellers’s greatest ever performance, Being There lives on as a satirical masterpiece that says as much about America in 2024, and beyond, as ever.

Ashby has been unjustly overlooked as a director, with Being There representing the end of a remarkable run that included the Seventies films The Last Detail, Coming Home and Shampoo. Yet it is the novelist and screenwriter Jerzy Kosinski whose imagination inspired the film, and whose life and career have strange and possibly uncomfortable parallels with the enigmatic figure at the heart of his best-known work. He grew up in grim and difficult circumstances, rose to near-unimaginable fame and fortune as a literary lion in New York, and died by his own hand in 1991, discredited and disgraced. Who was the “real” Kosinski, and why did his life come to resemble a fairground rollercoaster?

He was born Józef Lewinkopf in Poland in 1933, to Jewish parents, and the family spent the years of World War Two living as Catholics, thanks to forged documents provided by sympathetic villagers and clergy. The experience was formative for the young Kosinski, who was aware from this early age of the benefits of dissimulation and creating his own myth. When communism took over from fascism after the war, Kosinski, who was not prepared to be a yes-man under any regime, decided to emigrate to America at the age of twenty-four and pursue a literary career.

Here, as with so many other things in Kosinski’s life, fact and fiction appear to blur. He later admitted to faking correspondence from a self-created foundation that would “sponsor” his time in the United States, and then spent a strange and rackety few years that included everything from truck driving to taking a literature degree from Columbia. Before he was thirty, he had published two books under the pseudonym “Joseph Novak,” and had met his first wife Mary Hayward Weir, a millionaire socialite and steel heiress eighteen years his senior.

Just like Chauncey, Kosinski had emerged from nowhere, and yet became the most sought-after figure in Manhattan when the first book to be published under his real — if adopted — name, The Painted Bird, was released in 1965. A largely autobiographical account of the experiences of a naive boy in Eastern Europe during the war, it was promptly banned in Poland, drumming up useful amounts of publicity for the book. It was acclaimed as a masterpiece in the United States; Jonathan Yardley wrote in the Miami Herald that “Of all the remarkable fiction that emerged from World War Two, nothing stands higher than Jerzy Kosinski’s The Painted Bird. A magnificent work of art, and a celebration of the individual will. No one who reads it will forget it; no one who reads it will be unmoved by it.”

A stellar career was now assured, in addition to literary renown. Weir’s death in 1968 — they had divorced in 1966, after four years of marriage, and he was cut out of her will — he published the award-winning Steps the same year. Being There came out in 1971. Sellers read the book and became so obsessed by playing the central role that he begged Kosinski for much of the next decade to be allowed to buy the rights. He was eventually granted his wish, and amply justified Kosinski’s faith in him, winning several major awards that should have included an Oscar for Best Actor. Sellers believed, with some justification, that Ashby’s decision to include comic outtakes over the end credits dispelled much of the enigmatic power of the final scene and made it seem less significant in the eyes of Academy voters.

When the film was released, Kosinski was credited as sole screenwriter, despite having co-written the picture with Ashby’s regular collaborator Robert C. Jones: the latter described his failure to be credited as “a dark day in his life.” Jones had a significant impact on the film, changing the focus from a detached character study into something broader and more haunting. (It helped that Sellers, a man who once quipped “there used to be a real me, but I had it surgically removed,” believed that he was Chauncey Gardiner to a large extent, a savant who remained a blank slate on which a director — or an audience — could project whatever they wished.)

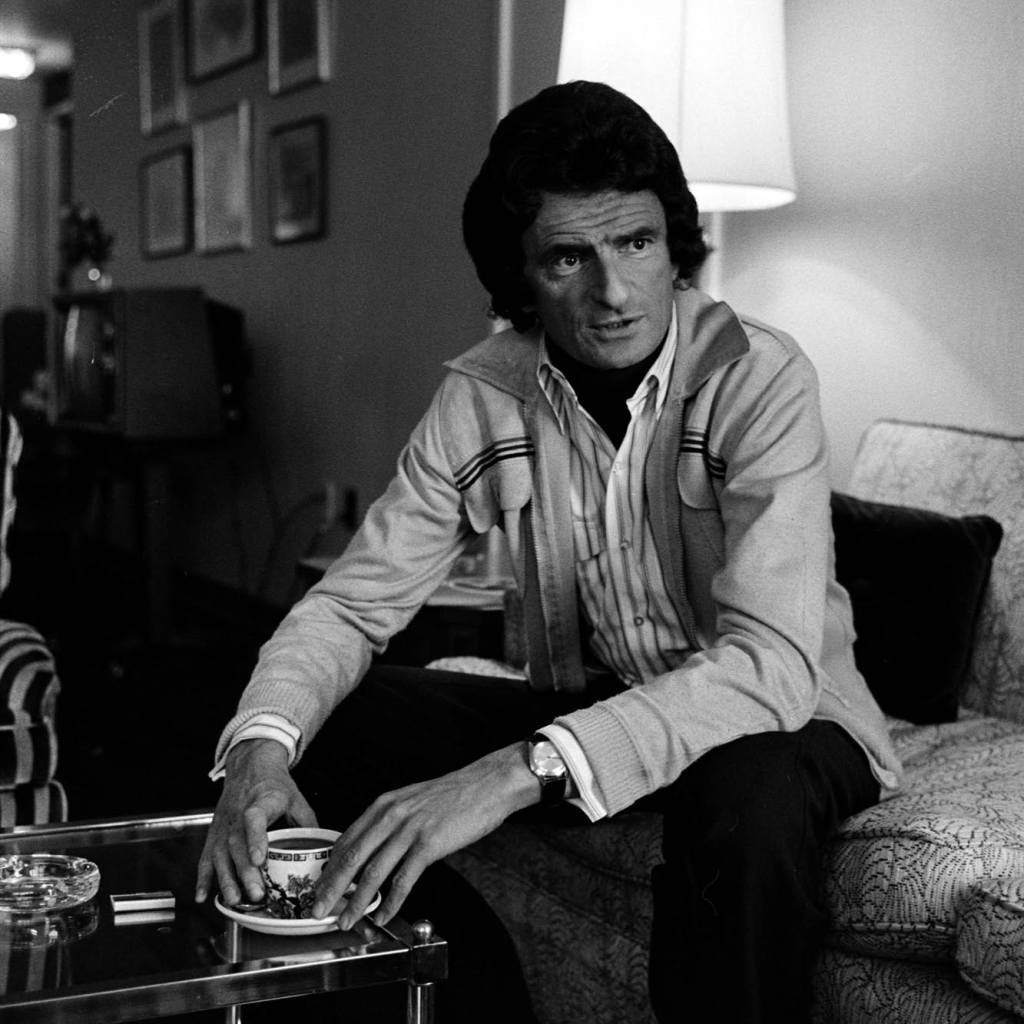

Kosinski won awards including a BAFTA and a Writers Guild of America accolade for “his” screenplay, and this, along with an acting appearance in his friend Warren Beatty’s Reds in 1981, seemed to cement his standing as a public figure in the United States. He dated multiple women, was a regular on Johnny Carson’s chat show and was photographed by Annie Leibovitz. Jerzy Kosinski was a celebrity.

He was also a fraud. A Village Voice investigation in 1982 suggested that The Painted Bird had been written in Polish by a committee of writers and editors and that Kosinski had taken the credit for it when it was translated into English at his behest. Further controversy arose when it was alleged that Being There was an Anglicized version of the 1932 Polish bestseller The Career of Nicodemus Dyzma by Tadeusz Dołęga-Mostowicz, which Kosinski would certainly have been aware of, but which had not received the same kind of attention in the United States. Kosinski denied the allegations — and was sufficiently well-regarded in the literary firmament for his friends and publishers to defend him publicly, but rumors of his grim personal behavior were eroding such ties.

He confessed in an interview that “I have always been fascinated by sexual experiences. I stop women on the street, introduce myself and say, ‘I like you. I want to photograph you.’” This may have been charming at first, but as his last novels were considerably more sexually explicit — some would say pornographic — it became clear that Kosinski had used his fame and reputation to act in a predatory way. Yet it did not bring him any kind of happiness. In a 1979 interview to support the release of Being There he said, “I’m not a suicide freak, but I want to be free. If I ever have an accident or a terminal disease that would affect my mind or my body, I will end it.”

Beset by depression over the plagiarism allegations and increasing physical frailty, on May 3, 1991, he consumed a large quantity of alcohol and drugs, got into a bathtub and placed a plastic bag around his head. The suicide note that he left said simply “I am going to put myself to sleep now for a bit longer than usual. Call it Eternity.” He was widely acclaimed as one of the great transplanted American writers of his generation on his death, but now he is an all but forgotten figure, more famous for his involvement in Being There than for his once modish and now unread novels. Still, as long as the masterpiece based on his — and Dołęga-Mostowicz’s — work is watched and enjoyed by audiences, some part of this strange, enigmatic man will always remain alive.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s December 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply