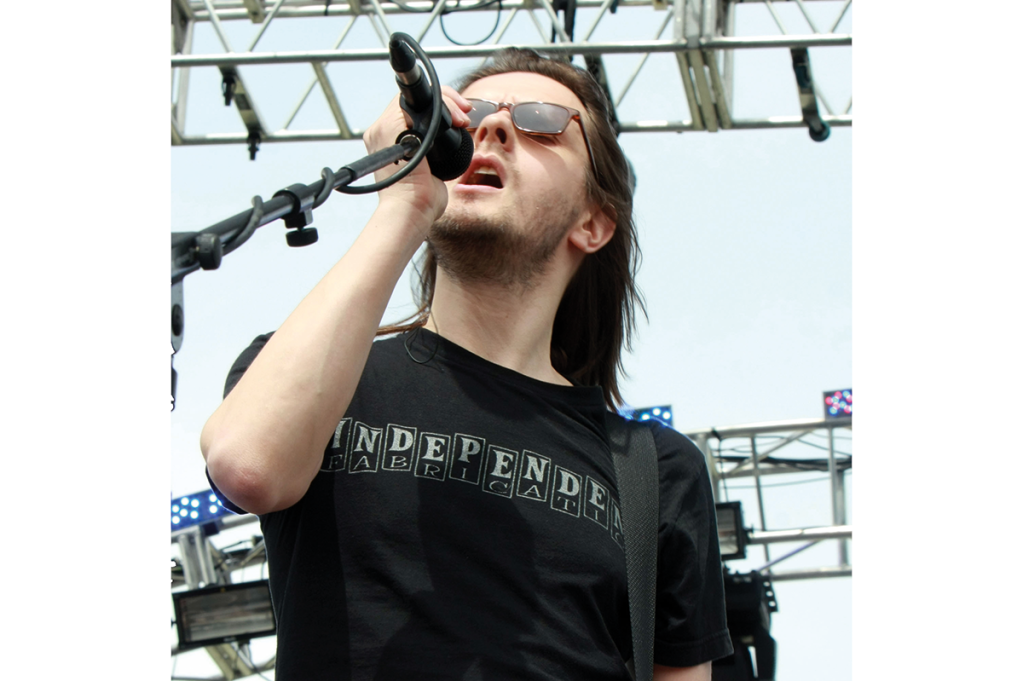

Steven Wilson is going about becoming a pop musician entirely the wrong way. For one thing, he’s into his fifties, not typically the point in life at which budding chart-botherers launch their assault on hearts and minds. For another, in an age in which pop stardom and identity politics have become entwined — in cultural discourse, at least, even if not necessarily in your teenager’s listening habits — he has everything going against him. ‘I come from a very well-adjusted family. I’m heterosexual. I’m white.’

Of course, Wilson doesn’t really expect to be competing against Stormzy and Dua Lipa and Cardi B. His new album, The Future Bites, is a markedly grown-up record, concerned with how algorithms are controlling the world, nodding to his own age (‘Now I just sit in the corner complaining/ Making out things were best in the 80s,’ he sings on the gorgeous ‘12 Things I Forgot’, a lambent, swelling song not a million miles from Pink Floyd at their most concise), and varying in style from the pulsing electronica of ‘Personal Shopper’ to the jagged funk of ‘Eminent Sleaze’. It’s terrific, from front to back.

Nor would he be able to compete with those artists. As he notes, the streaming services that have supplanted radio as the main disseminator of new music don’t have a lot of time for people like him. ‘Spotify has a kind of unwritten bias towards urban music and electronic music, which is fine. But it makes someone like myself, who is perceived to come from the tradition of rock music, persona non grata essentially. Part of the issue for me has always been that people don’t listen. They’ve already made up their mind.’

If that makes it sound as though Wilson is embarking on some late-life vanity project, he’s not. He’s a hugely successful musician; he just happens to have pursued the vast majority of his career in the shadows of genre. Specifically, in the shadows of a genre that no one, bar its adherents, pays any attention to: prog rock. As the leader of Porcupine Tree, Wilson made 10 albums, as that group became the standard-bearers of modern prog. The Future Bites is his sixth solo record and there are dozens more, over an array of other projects — No-Man, Bass Communion, Incredible Expanding Mindfuck, Storm Corrosion, Blackfield, Continuum).

The transition to pop began on his 2017 album To the Bone, which reached number 3 on the UK album charts and caused a great deal of consternation among the prog legions for betraying his past.

‘I don’t feel like I’m doing the right thing unless people are upset,’ Wilson says. ‘I always talk about people like Bowie and Zappa and Neil Young and Kate Bush as being role models, in the sense of how they conducted their careers — that constant sense of reinvention and confronting audience expectations. But at the same time, I’m also conscious that it was easier for them, because I live in the age of social media. The problem with social media is that you get a response within five minutes of doing anything. You release a new song into the world, which might be different to anything you’ve done before, and literally within minutes you have an incredible wave of feedback, much of which will be negative. And I’ve come to like that. Maybe I’m a masochist. I prefer that to the indifference that most bands who just recycle everything over and over again get. Like the fans will go, “We love this. More of the same.” I feel that’s too easy and too lazy.’

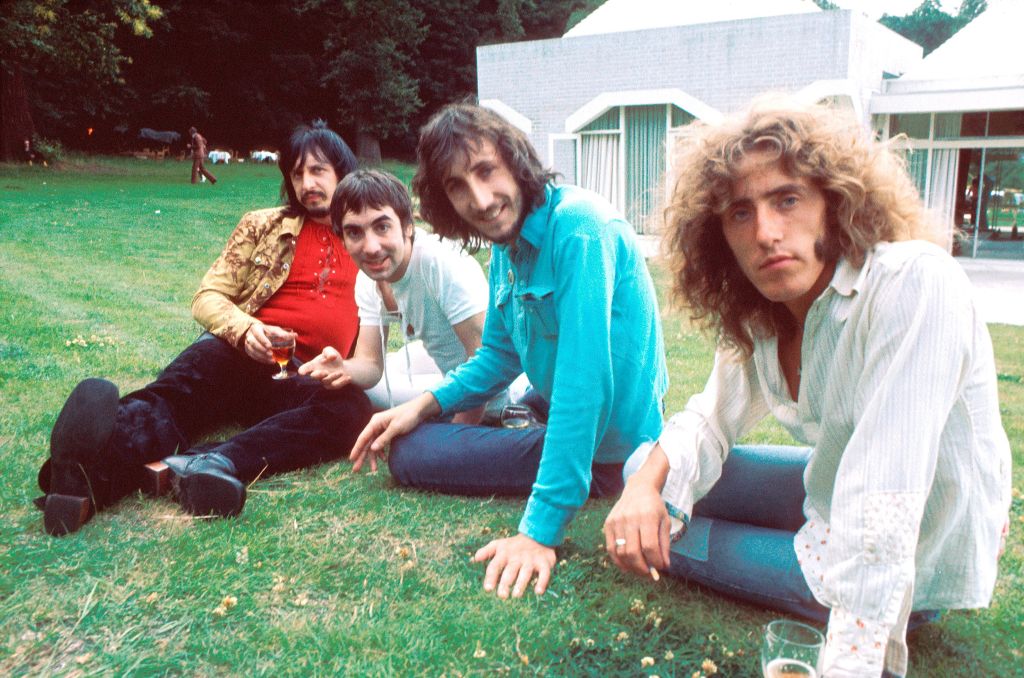

The movement from prog to pop has not always been a fertile one. In the 1980s, people whose careers had been based on getting far out at great length tried to shave 17 minutes off the length of their songs and write choruses. But for every ‘Owner of a Lonely Heart’ by Yes — a genuinely brilliant record that owed everything to the production genius of Trevor Horn — there was a Wildest Dreams by Asia, possibly the worst record ever made.

‘The 1980s are littered with terrible attempts by prog rock musicians to transition into the world of pop music. And I think you have to blame Trevor Horn for that,’ Wilson says. ‘A lot of people looked at it and thought, “We’ll have a piece of that.” And so you had a series of terrible, terrible compromise records, which failed to bring the old fans over or win any new fans.’ So what’s different about Wilson’s move to pop? Well, he says, for a start he’s always loved pop; he grew up on the clever pop of the 1980s — Talk Talk and Kate Bush and the Smiths and the Cure. And his first serious group, No-Man, played synth-pop. ‘I thought that was the one that would bring me success, but Porcupine Tree was the one that took off. I’m making the point that there’s always been more than one strand to who I was as a musician, and I don’t think that was true of Keith Emerson. So to anyone who’s followed my career in detail, The Future Bites isn’t as much of a surprise as it might have been. And it’s come from a place of deep love for electronic and pop music. It’s genuine, not something driven by the needs of the changing marketplace.’

Prog fans may well revere the technical prowess of the players who can solo from here to the end of next week — pausing only for some impenetrable lyrics about goodness knows what — but, Wilson says, it’s far harder to write pop songs. ‘I love the idea of the album as a continuum… I love the idea of the album as analogous to a movie or a piece of literature. I love the idea that people will sit down and listen to the album. But there is a difference between an album that has nine concise, relatively self-contained nuggets of melodic, experimental pop music, and an album that has three or four extended conceptual suites that go off into widdly-woo. I think it’s easier to create a backdrop where the same chord sequence goes round for three minutes, and someone just basically solos over the top of it. It’s much harder to create 40 minutes of relatively concise, tightly arranged music that’s going to keep the attention of people who are not interested in the excess of musos.’ Take that, noodlers!

If you look at prog rock groups on Facebook, you’ll see what many of the fans make of all this. Some think he’s living up to the progressive part of prog rock and refusing to stand still. A great many others express their disgust (it’s hard not to see his recent cover of Taylor Swift’s ‘The Last Great American Dynasty’ — a great song, but very much not prog — as an epic and successful act of trolling). Wilson knows there are people who will hate his new record but will buy it anyway. ‘In a way I wish they wouldn’t. If you don’t like this, please don’t listen and please don’t feel like you have to buy it. But then they do, and they complain about it.’

For the rest of us, though, there’s nothing to complain about. Welcome, Steven Wilson, to the world of people who don’t need you to turn in ever-decreasing circles.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s May 2021 World edition.