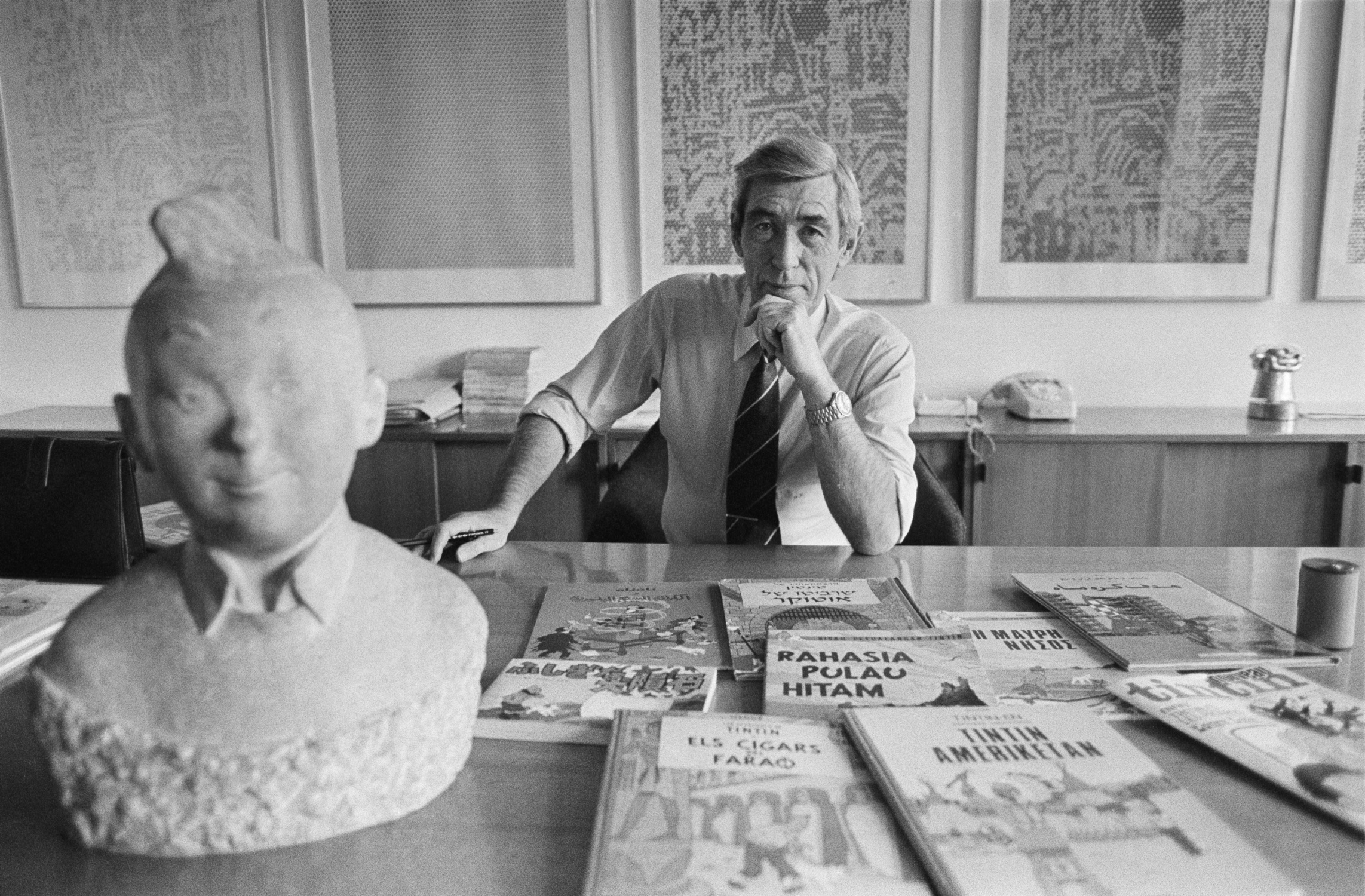

Georges Remi, better known as Hergé, the creator of Tintin, was a failed journalist. His first job after leaving school was on a Brussels newspaper, Le Vingtième Siècle, but boringly in the subscriptions department. His mind was set on becoming a top foreign correspondent like some of the leading names of the 1920s.

Having failed to join the ranks of renowned reporters, Hergé had created one in Tintin

He really had started on the bottom rung, for subscriptions were located in the basement of the newspaper building. At every opportunity he would migrate upstairs, to the busy newsroom and especially to the cuttings library, where he discovered the world at his fingertips. There he found and could browse through the international press, otherwise not so readily available in Brussels. He was able to develop a lifelong passion for current affairs.

There was a bonus too. On the back page of American newspapers, he discovered strip cartoons, then almost unknown in Europe. These gave him ideas of his own which he could soon develop.

Back in the basement, going through the subscriptions, he would pass the time doodling and drawing, and this was noticed by the editor’s secretary when she came down to check an address. She was impressed and mentioned the young man’s evident ability to the editor. At a time when newspapers only used photography sparingly, illustrations could be a useful substitute and Hergé was elevated from the basement and given a brief to provide illustrations for various parts of the paper: the literary and arts pages, fashion and even sport.

The editor’s next bright idea was to launch a children’s supplement, Le Petit Vingtième, on Thursdays (a half-day in Belgian schools) and appoint Hergé — then only twenty-one-years-old — as its first editor. It was a bit thin at first as Hergé tried to draw together material from a variety of contributors, so he decided to bolster it with a regular contribution of his own, a strip cartoon featuring the adventures of a young reporter called Tintin. And so, on January 10, 1929, Tintin was first seen, boarding a train at Brussels’s Gare du Nord station bound for Moscow, via Berlin. The rest is history in every sense, the Tintin adventures mirroring the twentieth century and the youthful reporter achieving instant and lasting fame.

Having failed to join the ranks of renowned reporters and foreign correspondents himself, Hergé had created one in Tintin, who would prove to be much more durable and have wider international appeal. Tintin was in effect his alter ego, reflecting his intense interest in news and contemporary affairs and longing to travel to far-flung destinations and discover the world.

It is sometimes observed, as a criticism, that Tintin throughout his fifty-year career is only seen writing a dispatch on one occasion, in the first adventure Tintin in the Land of the Soviets. There he compiles an overlong dispatch, spilling from desk to floor, which no editor would welcome. But he is seen notebook in hand dashing to the Museum of Ethnography after the theft of the fetish in The Broken Ear or interviewing the managing director of the oil company in Land of Black Gold. At other times he is as much a detective as investigative reporter. At all times, however, Hergé is a master of his well-researched facts for which he built up a formidable cuttings library, or archive, of his own on the widest range of subjects for possible future use. This explains why so many of the Tintin adventures are so forward-looking, even sometimes prescient.

Already in that first Soviet adventure, we have the Bolsheviks seizing the grain of the peasant farmers for their own stockpiles, leading to famine and starvation. Hergé had read up on the Soviet grain procurement crisis of the previous year (1928) and in his narrative anticipates the alienation of grain and property from the kulaks, the land-owning peasantry, that came in 1930-31 after the book’s publication. The Great Famine of 1932-33 that killed millions of Ukrainians and others followed as a consequence of Stalin’s policies, exposed by Tintin and condemned by Hergé.

Politics was never far from Hergé’s agenda. National Guardsmen drive Native Americans off the reservation at bayonet point after oil has been struck on their land in Tintin in America (1932). But the next deep political involvement came with The Blue Lotus in 1934. Here, against the trend of western sentiment, Hergé sided with the Chinese against Japanese agitation and aggression in Manchuria. He depicts the staged Mukden incident when in September 1931 Japanese saboteurs blew up the South Manchuria Railway tracks.

The Japanese military deceitfully blamed the Chinese and had their excuse for occupation. Censured for their action in a report fifteen months later, they walked out of the League of Nations in February. In a stunning page, Hergé depicts the sequence of events, including the military build-up with battleships at sea, squadrons of aircraft flying in formation and armored trains rumbling to strategic points. It is a chilling overture to and anticipation of the attack on Pearl Harbor which followed a decade on.

It was a bold and unpopular step by Hergé, for Japan had long been admired in the West for its culture and art, and its alliance with France and Britain in World War One. The Chinese, by comparison, were considered primitive and remembered for the cruelties of the Boxer Rebellion. Retired colonels wrote letters of complaint to Hergé’s newspaper, while Japanese diplomats lodged a protest with the foreign ministry.

But there was gratitude from an increasingly oppressed China. Hergé received an invitation to visit from the Nationalist government which he took up nearly forty years later when he visited Taiwan.

Politics was also at the core of King Ottokar’s Scepter (1938) inspired by Nazi Germany’s Anschluss, or absorption of neighboring Austria, in March of that year and anticipating its takeover of the Sudetenland and the threat posed to some of the vulnerable kingdoms of central Europe. Tintin thwarts the plot hatched by the unsubtly named fascist Müsstler — an amalgamation of Mussolini and Hitler — allowing the king to retain his throne and his kingdom, the fictional Balkan nation of Syldavia, to remain intact.

World war was on the brink of breaking out and soon Brussels, for the second time in a generation, was under German occupation. As a Catholic newspaper, Le Vingtième Sièclewas immediately shut down by the Nazis, leaving Hergé and Tintin unemployed. But they did not have to wait long before the editor of Belgium’s leading daily, Le Soir, invited them to join and set up a supplement for children, Le Soir Jeunesse.

Tintin could continue to cheer up Belgians, but Hergé had to be careful about politics, for within weeks the Nazis took control of the newspaper. His answer was to embark on escapism and the adventures of the wartime years safely concerned drugs trafficking, tracking a fallen meteorite, a treasure hunt and resolving a kidnap. Despite appearing in what had become a tainted newspaper, Tintin was a tremendous morale booster to oppressed Belgians in those difficult war years, according to the many I have spoken to, including Résistants.

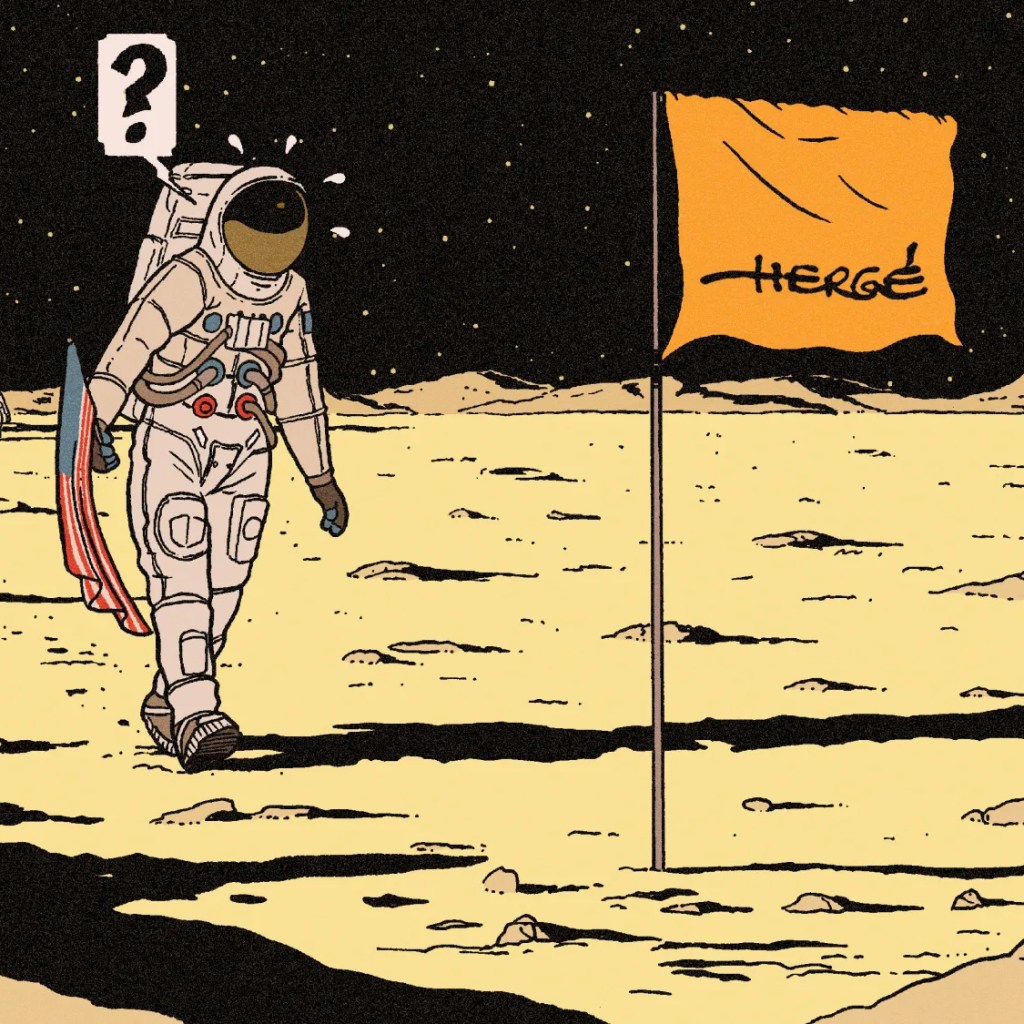

After the war, Tintin was again free to look for inspiration to current affairs and beyond. Hergé’s interest in contemporary developments extended beyond politics to science, and his most remarkable achievement was to send Tintin and his associates to the Moon and back in conditions of extraordinary accuracy, sixteen years before Neil Armstrong and the Apollo 11 mission. Hergé had begun to form an interest in the possibility of space travel already in the late 1940s and took out subscriptions to various scientific journals, and most importantly Collier’s magazine, where he could read articles by, among others, Wernher von Braun, who had led the Nazi rocket program and been poached by the Americans for their development of the Saturn rocket. He was, more-over, in contact with experts in Europe such as Professor Alexandre Ananoff in Paris and Dr. Bernard Heuvelmans in Brussels. He had enough material to begin the two-book adventure in Tintin magazine in March 1950 and to complete it with the reporter’s return to terra firma in December 1953.

There are, hardly surprisingly, a few inaccuracies, such as the use of nuclear fuel which was at first thought necessary before it became possible to refine extremely high-grade aviation spirit, but for the most part the picture is amazingly prophetic. Tintin finds an ice cave on the moon: this was dismissed by scientists at the time but has since been found to be quite feasible.

There are other instances of Hergé’s prescience. He had built up a bulging file on sightings of UFOs and decided to put this to use in Flight 714 to Sydney, where one such object appears towards the end. We are still waiting for any proof, and Hergé once admitted to me over lunch that “perhaps I went too far.” In the book that became his personal favorite, Tintin in Tibet, he introduces the Yeti, the so-called Abominable Snowman, frightening but hugely sympathetic. Again, we are still waiting but, in this case, if and when he is found, I am quite sure he will be just as Hergé portrayed him.

Michael Farr joined The Edition podcast’s Christmas special to discuss his article, alongside the author Anthony Horowitz: