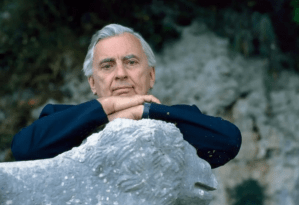

Back in the winter of 1980, a young Martin Amis found himself on the London set of Miloš Forman’s movie Ragtime. The plan was to inspect what Norman Mailer, whom Amis was profiling for the Observer newspaper, was doing with the part of Stanford White, the real-life architect murdered by the deranged husband of New York chorus girl Evelyn Nesbit.

Impressed by the lavish million-dollar backdrop, Amis looked on as the nattily dressed and neatly bewigged author of The Executioner’s Song, accompanied by his sixth wife, Norris, made his way into a reconstruction of Madison Square Garden.

There is, of course, something deeply symbolic about this juxtaposition: an aspiring great British novelist – Amis’s Money was still four years off – runs the rule over a great, if somewhat battered, American novelist, who is himself appearing in the movie of someone else’s (allegedly) great American novel. A modern version of that day on set is simply unimaginable. There may be one or two great American novelists still hunkered down in their book-filled studies in Poughkeepsie or at the Iowa Writers’ School, but their transatlantic equivalent has long since disappeared. Where is the contemporary work capable of attracting this kind of all-round media excitement?

Ragtime offers a panorama whose economic and moral implications are compromised by sheer excitement

The exacting British critic F.R. Leavis once proposed that the Sitwell siblings – Edith, Osbert and Sacheverell – belonged not to the history of poetry, but to the history of publicity. The same, once you substitute “fiction” for “poetry,” has several times been said of E.L. Doctorow’s Ragtime, which this summer celebrates a half-century on the bookshelves. Almost from the moment that the original manuscript slid across a publisher’s desk at Random House, the book was hyped with fervor. “It will be the most accoladed novel of this year,” the New Republic predicted; Newsweek reckoned it was “as exhilarating as a deep breath of pure oxygen.” The broadsheet reviewers followed their lead. In book-trade history, industry veterans say Ragtime received the wildest reception of any American novel since The Naked and the Dead – there’s that Mailer comparison again – back in 1948. A quarter of a million hardback copies were snapped up in under a year. The paperback rights went for $1.85 million.

Dino de Laurentiis, barreling in for the film deal, was thought to have cost his backers at Paramount a further million. And all this is to ignore the summer’s publicity cavalcade, which at one point saw a White Sox vs. Yankees game at Chicago’s Comiskey Park turn into a “Ragtime Night” featuring ushers wearing skimmers and gartered shirts, bands playing turn-of-the-century tunes and an antique car rally. Doctorow, whose three previous novels had sunk without trace, had suddenly become a public figure.

As nearly always happens in the aftermath of a publicity tornado, backlash quickly set in. When published in the UK the following spring, the novel was glacially disparaged: it read as if it had been written by a computer, sniffed the Listener’s reviewer Emma Tennant. Meanwhile, American critics, who had since divined something of the novel’s political underpinning, were hastening to take a second look. None was quite so acid as Commentary’s Hilton Kramer, who declared that “our culture is now so completely permeated with the myth of American malevolence that an ambitious political romance like Ragtime which distorts the actual materials of history with a fierce ideological arrogance is no longer in any danger of being recognized as having a blunt political point.”

Kramer goes on to condemn both reviewers and readers, who together comprise “an educated class that has grown morally obtuse about the world in which it lives and prospers.” Kramer recognizes the novel’s ambition, but links it to a morale-sapping national myth. He accuses it of distorting history and displaying political arrogance. Then there is his diagnosis of the put-up job of its reception. There is a strong hint of decadence – America, on the cusp of its centenary, delighting in believing itself founded on guilt, misrepresentation and a straightforward (or perhaps not so straightforward) lack of moral delicacy.

Steering a path between the towering heaps of garlands and brickbats that attended Ragtime’s 50-year-old debut is not always easy. Doctorow’s assault on the north face of the great American novel is made all the more conspicuous by its echoes of other great American novels, including those by the likes of Theodore Dreiser and Upton Sinclair. “Coincidentally,” Doctorow tells us, early on in the narrative, “this was the time in our history when the morose novelist Theodore Dreiser was suffering terribly from the bad reviews and negligible sales of his first book, Sister Carrie.”

There follows a queer little vignette of the out-of-work novelist holed up in his Brooklyn bedsit, spending long, neurotic hours seeking the “proper alignment” of his chair.

Ragtime is full of neurosis, of characters desperately trying to resolve the question of their own alignment to the world and the acute dissatisfaction they feel when nervous within it. To its terrific sense of potential – that characteristic early 20th-century American vista of big cities, fast cars and new horizons – can be added the dead weight of the robber-baron capitalism anatomized in Jack London’s pre-Orwellian dystopia The Iron Heel (1907).

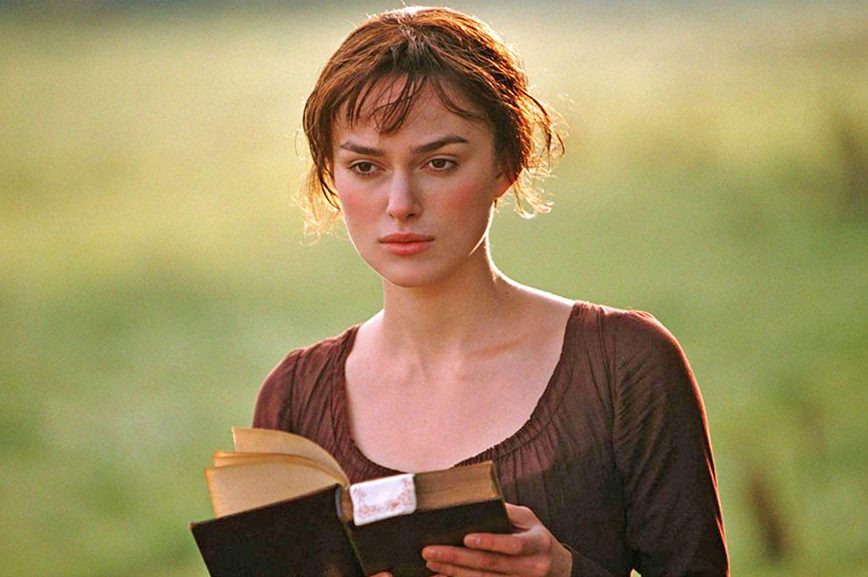

This contrast is marked by Doctorow’s habit of bringing in real people. Harry Houdini, Nesbit and her imprisoned husband Harry K. Thaw, J.P. Morgan. Henry Ford, anarchist Emma Goldman and black American leader Booker T. Washington all play key roles in coaxing the action forward and impinging on the lives of the more workaday characters who make up the rest of Doctorow’s teeming cast.

An odd kind of anonymity prevails. The family whose peaceful domicile in suburban New York and adventures within and beyond it the novel so remorselessly chronicles, go unnamed. “Father” manufactures fireworks. “Mother” has taken in a distressed black woman named Sarah and her baby. The erratic behavior of “Mother’s Younger Brother,” who stalks and at one point contrives a brief affair with Nesbit, gives cause for concern.

All this is observed by a small boy, who is well placed to observe the visits of the baby’s father, a black musician named Coalhouse Walker Jr. The desecration of his high-end car by a racist fire chief will lead to Sarah’s death, followed by insurrection, hostage-taking and a notably tense stand-off at the Morgan Library that will end with Walker’s slaughter in a hail of bullets.

Ragtime’s best quality lies in the terseness that enables many of its political points to be made by stealth

Like many a contender for the crown of the great American novel, Ragtime offers a panorama whose economic and moral implications are sometimes compromised by sheer excitement. When Tateh the street artist, who will later reinvent himself as a movie producer and marry the widowed “Mother,” sells his first flip-book of drawings to a novelty book company, Doctorow notes that “thus did the artist point his life along the lines of flow of American energy.” Workers may strike and die “but in the streets of cities an entrepreneur could cook sweet potatoes and sell them for a penny or two” and Frank the Cash Boy keeps his eye open for a runaway horse carrying the daughter of a Wall Street broker. Every town has its ice-cream soda fountain of Belgian marble and in Highland Park, Michigan, the first Model Ts are lurching down the ramp.

If there is a ruefulness to these accounts of the American capitalist machine creaking into gear, it is because you suspect that, deep down, Doctorow knows that his burning sense of injustice will never win enough votes. The seductions of the machine age, with its lovingly described trains (“five varnished dark green cars pulled by a Baldwin 4-4-0 with spoked engine truck wheels”) and its exotic paraphernalia are quite incontestable. Any American politician who urged a return to the Whitmanesque ideal of the country cottage surrounded by its picket fence and “freedom” would be written off as a half-wit.

The sting comes in his regular reminder that this is not an environment conducive to personal happiness. The small boy, watching his parents go about their daily lives, soon divines that “the world composed and recomposed itself constantly in an endless process of dissatisfaction.”

Doctorow died in 2015, acclaimed by Barack Obama, then president, as “one of America’s greatest novelists.” Ragtime’s best quality, it might be argued, lies in the economy of its style, the terseness that enables many of its political points to be made by stealth. Fatalism lurks on every corner, and the slow decline of the small boy’s grandfather, so enraptured by the thought of spring that he dances a jig, falls over and cracks his pelvis, will surprise no one who has paid close attention to the previous 160 pages.

But this, perhaps, is the lesson of great American novels: what begins as an exercise in morale-raising should end up as a series of dreadful warnings from the charnel house of a world gone horribly wrong.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s May 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply