When Brian Robbins, CEO of Paramount Studios, addressed the company in a town hall meeting on Tuesday, he was not in celebratory mood. Amid the grim and downbeat words he had to utter — “We know what a difficult and disruptive period it has been. And while we cannot say that the noise will disappear, we are here today to lay out a go-forward plan that can set us up for success no matter what path the company chooses to go down” — the news that the studio’s profits have declined by 61 precent over the past five years was described by Showtime CEO Chris McCarthy as “simply unacceptable.” Paramount is in big trouble. The only questions now are why, and what can be done to ameliorate the situation?

Last year, Paramount’s films underperformed consistently, a state of affairs maintained this year by the disappointment of John Krasinski’s expensive family picture IF. Such apparently cast-iron projects as Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny and Mission: Impossible — Dead Reckoning lost a lot of money at the box office, and while the Indiana Jones film was very bad and the Mission: Impossible picture very good, it didn’t matter to an audience who only wanted to go and see Barbenheimer, which made its respective studios, Warner and Universal, an almost indecent amount of money.

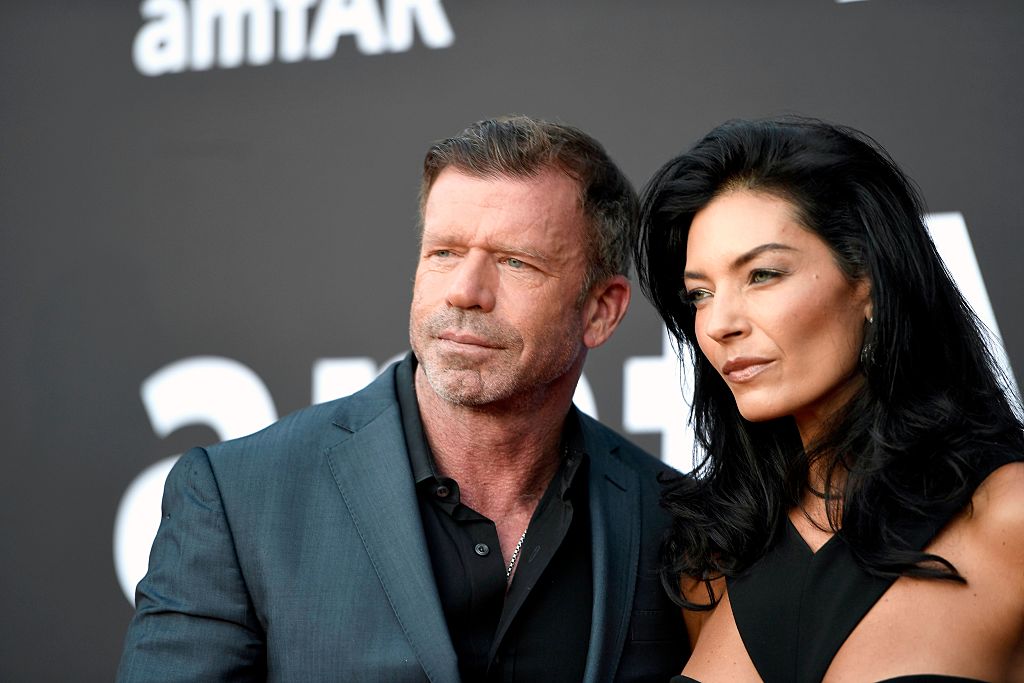

It says a great deal for the chaos at the heart of Paramount’s strategy that they had a chance to land Christopher Nolan and Oppenheimer — having previously collaborated with him on Interstellar — and muffed the opportunity, with Robbins’s focus on streaming-first meaning that they passed on the chance to bring Nolan into their stable, which in turn meant that Donna Langley at Universal was able to take on a project that made the best part of a billion dollars at the box office. By any stretch of the imagination, this was both an artistic and commercial oversight, just as Paramount’s fortunes on its streaming service Paramount + have been decidedly mixed. Their biggest crossover hit, Yellowstone, has lost its star Kevin Costner, amid reports of wrangling and disagreements between the actor and the showrunner Taylor Sheridan, and the next season will somehow have to write him out.

If this was an individual issue, then Robbins and his cohorts would simply shrug and move on; however, this is an ineffable sense that the studio simply isn’t pulling its weight in comparison to its competitors. This weekend’s Quiet Place prequel will no doubt be a modest box office hit, but it’s hardly screaming “unmissable appointment viewing,” and of the other movies coming this year, only the much-anticipated Gladiator sequel has the potential to be a huge crossover hit. There is more Transformers, more Sonic the Hedgehog, more Smurfs, for our sins. Next year, we will see if Liam Neeson can “do funny” in a Naked Gun reboot. But what there isn’t is any excitement or any innovation. Paramount is, famously, the studio that brought the world The Godfather. Now, if it rebooted or remade the picture, it would probably hire Michael Bay to direct, cast Ryan Reynolds as Michael Corleone, and hope for the best.

Can anything be done? Well the fact that Robbins realizes that there is a problem is a step in the right direction, although corporate-speak about “streamlining assets” and the like is an act of panic, rather than strategy. A better and more lucrative idea would be to recognize that making endless derivative sequels and low-grade TV shows is not the way forward (why oh why did anyone think a Sexy Beast prequel was a good idea?) and to nurture talent (yes, including Costner) at the highest levels. Tom Cruise will not go on forever, ageless though he appears. If proper action is taken, then the situation is redeemable. If not, then there will be many more grim faces at town hall meetings, and one day Paramount will join the ranks of so many other former studios, gone but not forgotten. Which would be an existential shame for the beleaguered entertainment industry.

Leave a Reply