When I was a teenager whiling away the endless hours with VHS video rentals, Vietnam movies were pretty much the only game in town. I must have watched The Deerhunter a dozen times, and the scene in the rat-infested river cage well over a hundred times. Even now, I can’t watch it without being surprised at how De Niro manages to pull off that extraordinary escape stunt. My, how I covet those tiger-stripe Special Forces camouflage fatigues.

The problem is, The Deerhunter has loads of boring non-war stuff either side of the good bits. That’s why I much prefer Platoon — controversial choice, Oliver Stone being a pinko — all of which takes place in-country. And of course the Mother of all Nam movies, Apocalypse Now, whose air cavalry assault on the village not only has the best soundtrack (‘Ride of the Valkyries’) and the best one liners (‘Napalm in the morning’; ‘Charlie don’t surf’), but also the most satisfying pyrotechnic smörgåsbord: rockets from the choppers, spraying with the .50-cal door guns; that napalm strike on the tree line; and that evil VC woman who runs to the chopper holding what you think is a baby only it’s —no! you should have shot her as she approached! — a bomb.

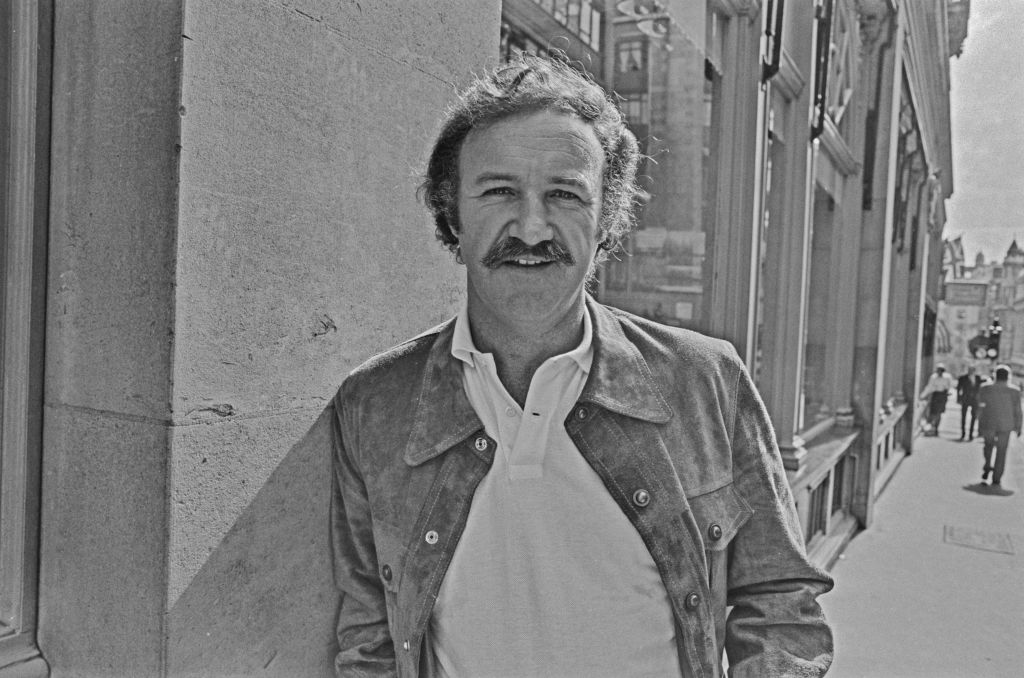

Real Nam movie connoisseurs recognize that the obscure ones are often the best: Go Tell the Spartans with Burt Lancaster, whose most horrifying scene is when they go to the perimeter to check on mosquito density, because I fear and loathe mosquitos even more than I do Charlie; and The Odd Angry Shot, especially the scene where the boys, barely suppressing their smirks, hand the padre a shoebox with a hole in one end and a crank on the side which rotates some feathers inside. ‘Boys,’ he says, gratefully. ‘That’s the best wanking machine I’ve ever seen.’

So imagine my excitement when, trawling Netflix for something new to watch, I alighted on a recent Nam movie called Danger Close. Like The Odd Angry Shot, it covers a little known aspect of the war: Australians and New Zealanders fought there alongside Americans. Danger Close concerns the Battle of the Long Tan in 1966, when one Aussie company of 108 men fought off a whole NVA division of perhaps 2,000 men.

I enjoyed it very much. Thanks to Saving Private Ryan, the bar for combat special effects is now so high that watching war on film is now almost as exciting, exhausting and overwhelming as I imagine it is for real. The whizzing of the rounds makes you want to duck; the dull thwack as one hits bone or flesh makes you want to heave. And because it’s a true story, the filmmakers have respectfully kept it all as grimy and echt as possible. There are no starry actors giving standout performances. As in war, it’s completely random who lives or dies, so don’t get too attached to any of the characters who you think have far too much personality to end up on the KIA list.

It’s also the best demonstration of the importance of artillery I’ve ever seen on film. When you’re a child fantasizing about war, it’s the bullets you worry about. But far more combatants die from shellfire and shrapnel. This is fortunately the case here, because if those bugle-blowing NVA hordes hadn’t been obliterated by the Royal Regiment of New Zealand Artillery, the Aussies would have been wiped out. ‘Danger close’ is the order for calling in artillery so close that it’s as likely to hit you as the enemy.

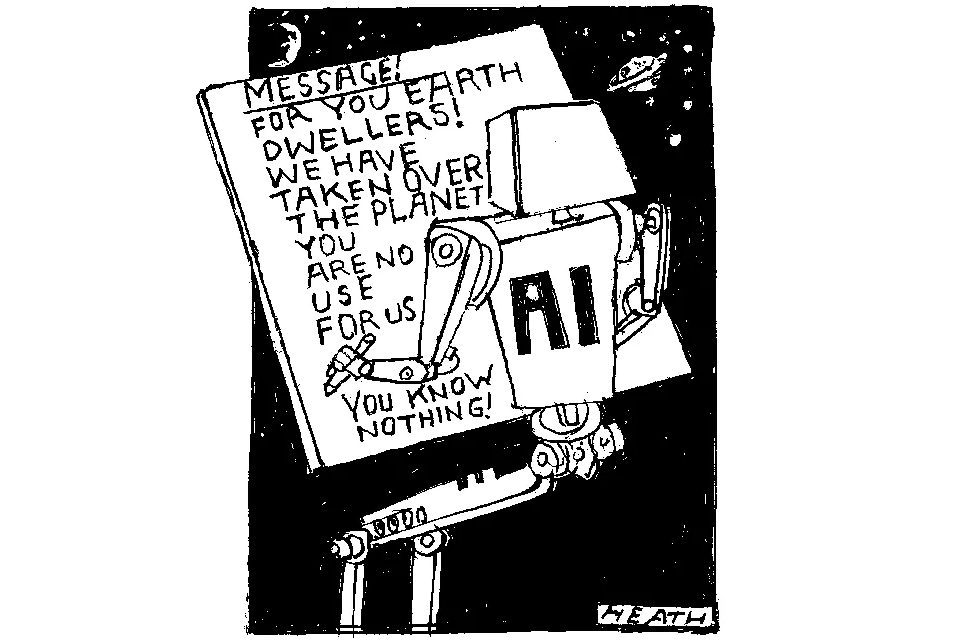

The most remarkable thing about Danger Close is that it was made at all. You only have to look at its fairly muted critical reception to see why. The basic problem is this: most reviewers are so insufferably woke these days, they won’t enthuse about movies that glorify combat or show western nations in an heroic light.

If a director from Hanoi made an epic entirely from the Vietnamese perspective about how his guys overwhelmed the French at Dien Bien Phu, I’d be more than happy to go see it. I really don’t expect — nor should any reasonable, hinged person with an IQ higher than an amoeba — my war movies to empathize with both sides. From at least the Iliad onwards, our civilization has cherished and celebrated and gloried in the heroism of our warriors, to remind us of the kind of behavior that is expected of us when our nations are under threat. It’s more than just entertainment; it’s ultimately about survival. Unfortunately, the leftists who infest Hollywood and most of the rest of the movie and TV industry don’t understand this. We’re probably doomed, but let’s hold out for reinforcements, just in case.

This article is in The Spectator’s October 2020 US edition.