‘This seems to be in your rough area. I mean, it contains wooden legs and everything…’ my commissioning editor at The Spectator emailed. He was requesting a review of Sonia Purnell’s excellent A Woman of No Importance, a biography of the remarkable Virginia Hall, the only World War Two agent to serve not only with Britain’s Special Operations Executive (SOE) and its later American counterpart, the OSS, but eventually also with the CIA.

It is perhaps unsurprising that war histories contain a high number of people with missing or prosthetic limbs. Many of those who served parted with their extremities during action, such as the would-be Hitler-assassin Claus von Stauffenberg (who lost one arm, one eye and many fingers), and the extraordinary Sir Adrian Canton de Wiart (who lost one leg, one eye, and tore off two of his own fingers when the surgeon wouldn’t amputate). Others, such as the Anglo-Polish special agent Andrew Kowerski-Kennedy and the American-born Hall, lost their limbs (a leg each) before the war, but never considered letting that impede them.

Hall shot a round into her foot from a 12-gauge shotgun at point-blank range in 1933. Snipe-shooting with friends in the marshes of what was then Smyrna in Turkey (she had already disappointed her mother by choosing a diplomatic career, that enabled her to travel, over ‘domestic bliss’ at home), she caught the barrel of her gun in her coat as she climbed a fence, only to discover she had not applied the safety catch. Later, Hall would develop ambivalent feelings towards her wooden and aluminum prosthetic, ‘held in place by leather straps and corsetry round her waist’. Instead of letting it define her, she externalized it to the point of naming it Cuthbert. Others found it harder to distinguish the woman from her disability. She was repeatedly denied jobs and promotion, and became known to the Nazis as ‘the limping lady’.

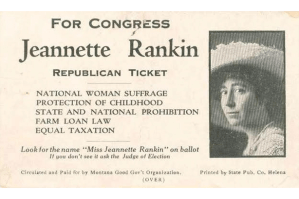

Ambitious and talented, Hall had learnt to defy prejudice long before her accident. Afterwards, she never asked for special dispensation, and many people never knew the extent of her injuries. The onset of war brought new opportunities. At a time when many men struggled to imagine that women could be involved in subversion, but able-bodied men moving around occupied territory automatically attracted attention, Hall had an advantage. SOE sent her to France to provide intelligence on troop movements, the location of ammunition and fuel dumps, and the development of war industries.

Soon Hall had also recruited women from convents and brothels, hair salons and hospitals to provide safe houses and help run escape lines. In one gripping 12-day operation, she coordinated the escape of a dozen male agents from incarceration. By September 1942, she was being hunted as one of the Allies’ ‘most dangerous’ agents. From fear of being deserted, she undertook a grueling hike to safety over the Pyrenees without letting her guide know about her prosthetic leg. One evening, having tended to her bloodied stump, she finally mentioned her discomfort to London by wireless. ‘If Cuthbert is tiresome,’ the uncomprehending reply came back, ‘have him eliminated.’

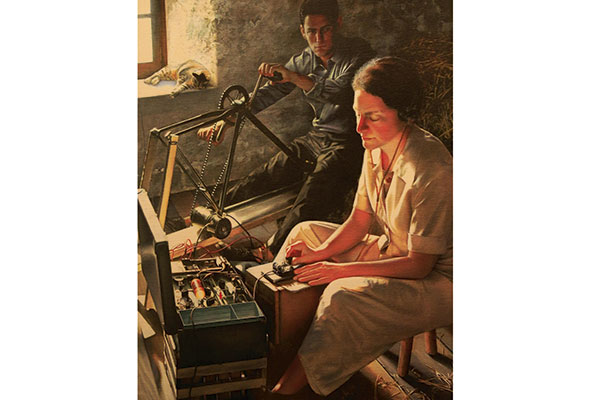

Hall returned to France in 1944, this time with the American OSS. Although it was inconceivable that she should officially be put in charge of operations, she was soon commanding 400 resistance fighters, making coordinated attacks on roads, railways, bridges and telephone lines in the run up to D-Day. ‘You have every reason to be proud of her,’ officials informed her mother. ‘Virginia is doing a spectacular man-sized job.’

Purnell’s meticulous research into Hall’s life and work has taken her not only through British SOE papers and resistance files in France, but also through nine levels of security at the CIA in Langley. The facts are right, so it is a pity to find a few sweeping statements, such as that Hall ‘alone… changed opinions about women in warfare’, when she was in fact one of several extremely effective female special agents. At the time, as the ironic title of this biography suggests, women were effective partly because they were so often considered to be ‘of no importance’. All too often since, such women are still celebrated for their courage and beauty rather than for their achievements. The great strength of this book is that Purnell has far too much respect for her subject to fall into that trap.

After D-Day, SOE commended Hall’s ‘truly amazing performance’. Back in the USA in 1945, she became the only civilian woman in the conflict to be awarded the Distinguished Service Cross. Yet CIA files from her postwar career refer to her as ‘he’ throughout, seemingly unable to countenance the fact of her gender. Whether Hall faced more prejudice because she lacked a leg or a penis is debatable. What this book makes evident is that sustained results in the field were down to the skill, character and to some extent the luck of each individual sent to serve, whether male or female, able-bodied or otherwise.

This article was originally published in The Spectator magazine.