When Dexys Midnight Runners reached Number 1 in the British singles charts in spring 1980 with the song ‘Geno’, the band had to travel to London for their coronation appearance on the weekly Top of the Pops television show. For the first time they could afford the train fare. But Kevin Rowland — their singer, leader, creative director, boss, whatever you want to call him — insisted they continue to jump the barriers at Birmingham New Street station.

‘I said, “Come on lads, we’re still going to bunk the trains.” And they went, “What?” “Come on, the inspector’s coming. We’ve got to get in the toilets.” And the drummer said, “Kev. We’re Number 1 in the charts and we’re bunking the trains…” “GET IN!” I don’t know why. It was probably a control thing. I was insecure then. It made me more insecure, the success, in a funny way. I only enjoyed being a pop star for a few weeks.’

And at the heart of that story are two things that define Kevin Rowland. The first is the commitment to an idea of what a band should be — or, perhaps, the overcommitment to an idea. For example, they might go out running each morning on tour, then appear on stage dressed in boxing boots and athletic wear (‘It wasn’t me dictating that we go training. But we nearly all started doing it. And it became a Dexys thing, so we decided to let people know about it’).

There would be different images for each phase of the group — the bedraggled gypsy look that accompanied ‘Come On Eileen’ is perhaps most famous, though the idea started with the beanies and leather jackets of their first incarnation (‘We tried to create an image of being tough, but we weren’t that bloody tough. Tough guys don’t join bands, not really’). And in front of them was always Rowland, a man whose voice — sometimes incomprehensible, certainly no one’s idea of perfect and full of yelps and howls and wordless tics — communicated a passion that could not be dimmed. When I introduce the idea that Rowland is one of Britain’s greatest soul singers (despite the critic Robert Christgau asserting that he ‘can’t carry a tune to the next note’), his unfussed reaction suggests he’s been told that before.

The second thing is the insecurity which haunted Rowland for decades and eventually led to My Beauty, his 1999 solo album, the reissue of which we are ostensibly discussing. He became a singer, he says, ‘to prove that I was not a piece of shit. That was it. I remember thinking around 1977, ’78, “If I get on Top of the Pops, I’ll have something that nobody I know has got. I’ll have done something that nobody I know has done. If I do well, nobody will be able to put me down.” That’s how I thought. It’s not true of course. Doesn’t work.’

After knocking Dexys on the head in the mid-1980s, following three albums (Searching For the Young Soul Rebels, Too-Rye-Ay and Don’t Stand Me Down, all classics), he sought to address his insecurities, but he did it the wrong way. He took so much cocaine he became an addict for several years. ‘I found it very seductive,’ he says. ‘All I know is it really appealed. It made me feel confident. Like I had something to say, and it gave me something, to begin with.’

Unfortunately, the debts Rowland had run up trying to achieve exactly what he wanted with the ever-changing and mob-handed lineups of Dexys were catching up with him, too. He was bankrupt between 1991 and 1994, and there was an 11-year gap between his first solo album, The Wanderer, and My Beauty. What was he doing in the intervening time? ‘Well, cocaine addiction is quite time-consuming. That was a good five, six, seven, eight years.’

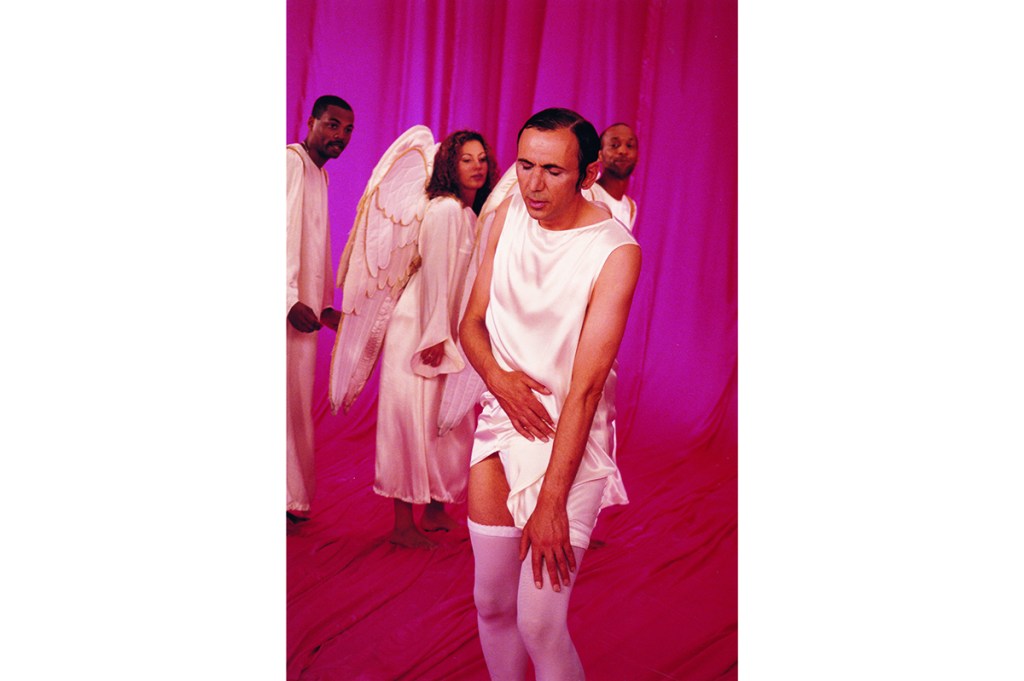

My Beauty came after he’d cleaned up, and after his finances were put back on track. Unfortunately, the world interpreted it differently. First, the cover featured Rowland in a midnight-blue dress, pulled off the shoulder at the top, and pulled up at the bottom to reveal panties and suspenders. He followed it with a badly received appearance at the Reading Festival, this time wearing a white dress. The record itself baffled many reviewers — it opened with a cover of ‘Greatest Love of All’, a song most closely associated with Whitney Houston. The response was immediate and pretty much unanimous: ‘Watch out! Rowland’s cracking up!’

He’s happy, now that it is being reissued, to be able to make the point that it was not his breakdown album but his recovery album. ‘The narrative at the time was just too strong. There are so many myths around My Beauty — that we got bottled off at Reading [music festival]. Bullshit. They were just selling myths that I was cracking up. And some of that came from people at the label. People were saying I was rescued from the scrapheap. That’s rubbish. I had a bank account, I had put down a deposit on a flat in Brighton. I was coming out of it.’

To be fair, though, he’d been out of the public eye for 11 years and returned in a dress. People were always going to be taken aback. ‘I can understand that, given the images of previous Dexys. Which is why I wished I hadn’t had a past at that point. I wished that I was a new artist. I wished this was a first album. There was nothing wrong with what I was doing — let me make that 100 percent clear. I’m proud of the look, I’m proud of the music. I was surprised they could be so narrow-minded. People who were supposedly on the left, or would consider themselves liberal-minded, it must have brought something up in them that was difficult for them to process.’

Nowadays, aged 66, Rowland is in London (he couldn’t get anything done in Brighton, he says. He had to move back). We meet in his apartment — a tidy little new-build in east London, overlooking one of the waterways. He had COVID-19 a while back, and says he tires easily and that it’s definitely affected his memory. But he still looks great: he’s much more dressed up than I am, and he considers all questions intensely, trying to hammer them down to specifics. The insecurities are still there, he says, but he can recognize them now. Still, though, ‘I spend far too much of my time thinking about myself and being conscious of myself. Far too much time,’ he says.

But through it all, there’s still a singularity of vision and purpose. If he wanted to, Rowland could put together a Dexys lineup from the 1980s (there have been two more in the past decade). He’d be rich if he did that — and it’s not from lack of demand from promoters. ‘But I wouldn’t do that,’ he says. ‘We only do what we think is right. No offense to the old fans, but we’re not in the business of reliving memories.’

If for one moment he could forget himself, swallow his qualms and take the cash, he could have a bigger apartment, overlooking a more picturesque waterway. He could afford to go to the studio and do what he wanted. But then he wouldn’t be Kevin Rowland any longer, and what would be the point of that?

My Beauty will be re-released on Cherry Red on September 25. This article is in The Spectator’s October 2020 US edition.