This article is in The Spectator’s March 2020 US edition. Subscribe here.

Velázquez prized his work, but El Greco’s reputation fell quickly after his death in 1614. Another Spanish painter, Antonio Palomino (1655-1726), called The Greek ‘contemptible and ridiculous, as much for the disjointed drawing as for the insipid colors’. In the 1800s, ‘The Burial of the Count of Orgaz’, now regarded as one of his masterpieces, lay rolled up in the basement of a Toledo church. Yet these days, El Greco, born Doménikos Theotokópoulos in Crete in 1541, is considered one of the great masters of western art — so great that, fewer than 20 years after a major retrospective at the Met and six years after another at the Prado, another large show has traveled from the Louvre to the Art Institute of Chicago. What happened?

El Greco’s rehabilitation began in the 19th century when nine of his canvases went on display at the Spanish galleries at the Louvre, allowing Cézanne to crib from him the deliberate extension of line beyond its expected endpoint. In 1920, the Bloomsbury painter, curator and critic Roger Fry supplied the now-standard view that El Greco was a modern before the art world knew what moderns were. Fry even claimed that El Greco was ‘an old master who is not merely modern, but actually appears a good many steps ahead of us, turning back to show us the way’. This, more or less, was the view of the Met’s retrospective in 2003. Its catalogue included El Greco endorsements from Van Gogh, Matisse, Picasso and Pollock, who was apt to fill his sketchbooks with copies of El Greco compositions; a pity he didn’t carry more of that over into his paintings. Flattered by apparent similarities between El Greco’s fractured art and our own, we moderns have prized him accordingly.

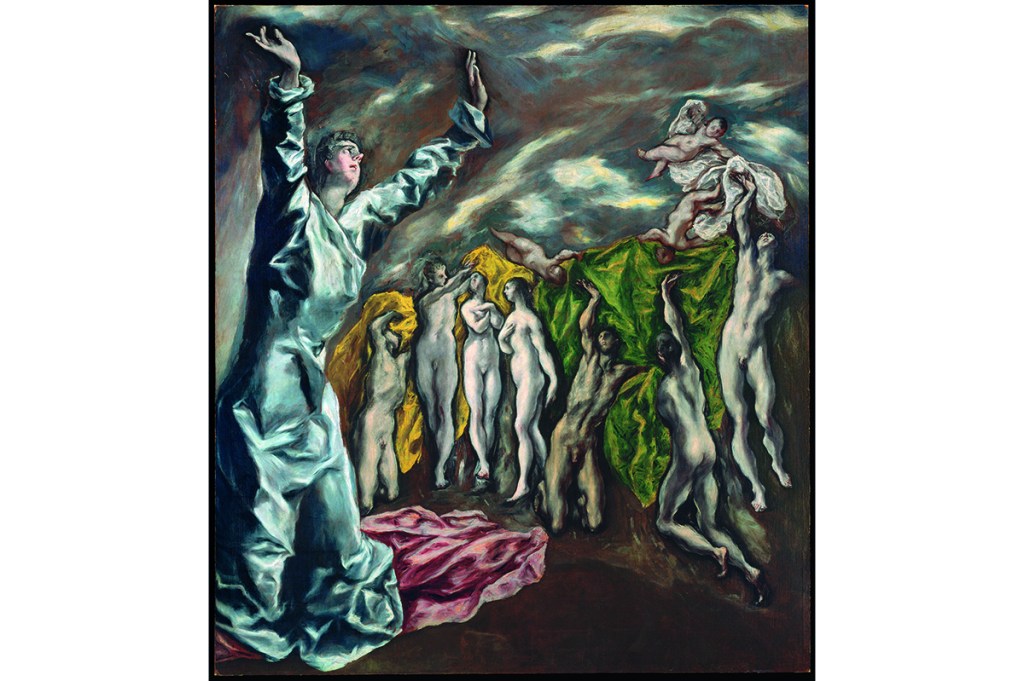

Looking at paintings such as the Met’s ‘Vision of Saint John’, also known as the ‘Opening of the Fifth Seal’ (c.1608-14), it’s easy to see El Greco as a proto-modern. Picasso knew this work well, having studied it in Paris while it was owned by his friend Ignacio Zuloaga, a painter and collector. Its elongated figures and cavorting nudes surely were sources for Picasso’s experiments in distortion in ‘Demoiselles d’Avignon’ (1907). Picasso’s biographer John Richardson, with characteristic flamboyance, went further, suggesting that Picasso ‘steals the thunder of El Greco’s altarpiece, harnesses its magic to his own demonic ends’. Perhaps.

Further evidence of El Greco’s precocious ‘modernism’ is supplied by his ‘View of Toledo’ (c.1598-99), which also comes to Chicago from the Met. Its abstraction of landscape and arguably deliberate misuse of perspective has something of the dark rural surrealism of Paul Nash (1889-1946). Robert Byron, writing in the Burlington Magazine in 1929 (before he took the road to Oxiana and reinvented travel writing), judged ‘View of Toledo’, with its ‘astonishing resemblance and affinity with the landscapes of Cézanne’, as the painting ‘in which more nearly than anything else, [El Greco] approaches the impressionist founders of modern art’.

But Byron’s association of El Greco and Cézanne is merely a small concession to the Roger Fry doctrine. Byron’s point was to suggest that El Greco’s work originated in the recent Byzantine tradition into which he was born: ‘it is plain that all El Greco’s most individual characteristics, which have so puzzled and dismayed his critics, derive directly from the art of his ancestors.’

So, not a time-traveling visionary after all? In Byron’s view it was a happy accident that the art of the 20th century should have so much to do with a painter from the 16th. El Greco’s art ‘simply exhibits the superlative of all the principles, which comprise the one principle of representational art, which the Byzantines discovered, and which have survived the vagaries of classical and rational taste for a further efflorescence in the twentieth century’. Against the jagged modernist mash-up of fashions and styles, El Greco was a repository of eternal traditions.

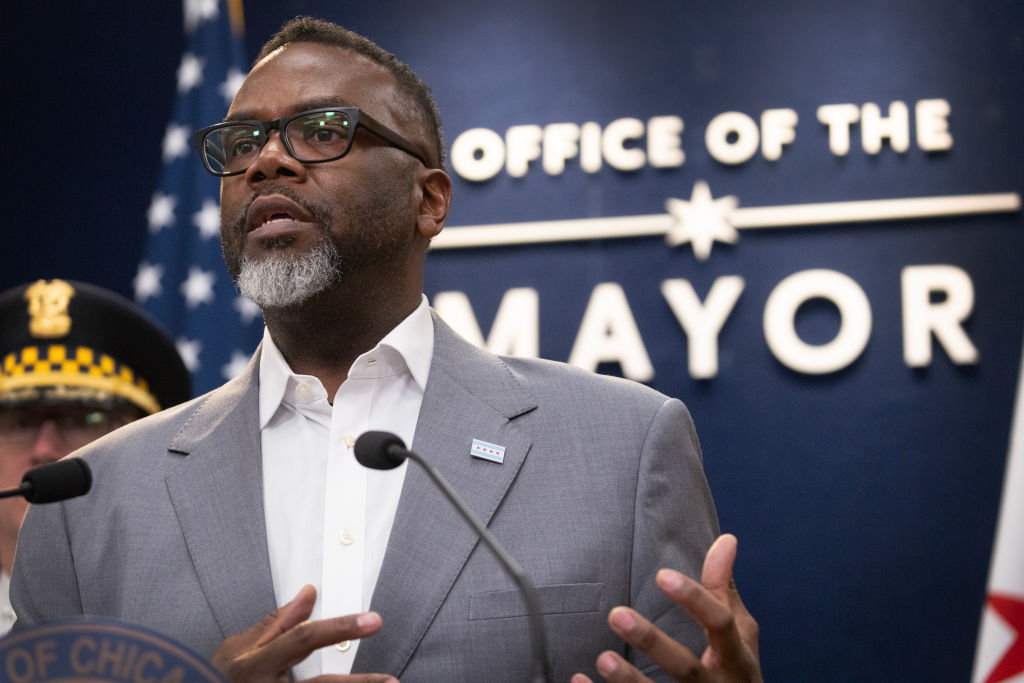

Rebecca J. Long, the curator of El Greco: Ambition and Defiance in Chicago, suggests a different way back to El Greco, one less interested in his 20th-century reputation and much more concerned with the mystery of the man — closer to Byron’s approach, if not his conclusions. Long asserts that while El Greco has ‘traditionally been considered through the lens of religious art’, we find a clearer view of him through ‘the lens of patronage’. He was ‘a striver’. If so, a particularly untactful one.

Things started well enough for the merchant’s son from Heraklion, where the locals still claim he learned anatomy from working in a butcher’s shop. He began by painting icons on Venetian-ruled Crete before traveling to Venice in 1567 to study under the master colorists Titian, Tintoretto and Veronese (the closeness of his association with all three is still not settled). The trouble started in Rome in 1570, where an auspicious introduction to Cardinal Alessandro Farnese, a major collector of antique sculpture and contemporary painting, resulted in El Greco taking rooms at the Palazzo Farnese. Such good fortune was allegedly repaid with insolence, a pattern to be repeated throughout El Greco’s life. When talk spread of revising Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel ‘Last Judgment’ to fit CounterReformation ideas of decency, El Greco put his oar in. A note in the Vatican Library records that he ‘declared that if the whole work were destroyed he could paint it again chastely and decently and just as well as the original as regards good pictorial execution’. According to the same source, ‘Such was the indignation of all the painters and lovers of art that [El Greco] found it expedient to remove to Spain.’ Arrivederci, Roma.

A practiced striver might have learned his lesson, but El Greco seems to have been unwilling to make nice, no matter the patron. His more than three decades in Toledo were artistically fruitful, resulting in hundreds of commissions, but with El Greco often taking his patrons to court over their unwillingness to foot his high fees. Some of the cases weren’t resolved until after his death; his son Jorge haggled on behalf of his estate.

No wonder Philip II was wary. In the late 1570s, the king commissioned the complicated painting now known as ‘The Adoration of the Name of Jesus’, which comes to Chicago from London. After that, however, El Greco received only one further royal commission, for ‘The Martyrdom of St Maurice’ (1580- 82). Philip II assented to El Greco’s complaints of insufficient paints and funds, but that was the end of the artist’s royal career.

Despite this disappointment, El Greco still found plenty of work from religious organizations and private patrons, who prized his three-quarter-length portraits, a characteristic selection of which is on show in Chicago. Particularly beguiling is ‘Fray Hortensio Félix Paravicino’ (1609), on loan from the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, which bought it on John Singer Sargent’s advice. Alternating blocks of black and white fabric frame the friar’s wary head, while delicate hands slither out of his sleeves.

El Greco’s patrons tolerated his petulance because of his singular ability. With the charged colors of Veronese and a way of treating the human form all his own, an El Greco couldn’t be confused with a work by anybody else. Alternative explanations for his singularity and appeal have been attempted, some more plausible than others. Somerset Maugham attributed his ‘tortured fantasy and sinister strangeness’ to latent homosexuality — a theory both deterred and bolstered by El Greco having had a common-law wife and a son. Then there was Dr Arturo Perera, who wrote in the 1950s in a scholarly journal of Spanish art that El Greco’s style was down to the use of hashish.

More commonly, El Greco has been assumed to have had some vision problem, either astigmatism (blurred vision) or strabismus (crossed eyes). Robert Byron dismissed the ocular theories as ‘complacent’. Aldous Huxley, who experienced sight problems of his own, wrote that though it was ‘likely enough that El Greco had something wrong with his eyes’, it was ‘absurd’ to equate his art with defective eyesight: ‘he was a man who used a defective eyesight.’ Huxley offered a further theory, half in jest — in El Greco’s paintings, all the characters, so physiologically affected by the visceral world around them, are ‘situated in the belly of a whale’.

Visitors to Chicago will delight in the more than 50 works on show regardless of which theory they like best. And while Huxley, attendant at the Bloomsbury-sponsored El Greco revival, is no longer remembered as an art critic, El Greco himself has survived his 20th-century resurrection and remains visually timeless — iconic, even — in our brave new 21st-century world.

This article is in The Spectator’s March 2020 US edition. Subscribe here.