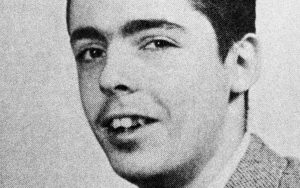

Ocean Vuong’s writing is heavily influenced by his own experiences. The protagonist of his first coming-of-age novel, On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous, is a carbon-copy of the author. Vuong was born in Vietnam in 1988.

While serving with the US Navy, his American grandfather fell in love with “an illiterate girl from the rice paddies” who gave him three children. When one of them, Vuong’s mother, was identified as mixed-race by a policeman, the family was displaced to a refugee camp in the Philippines and finally made it to Hartford, Connecticut, where Vuong was raised by his mother, aunt and grandmother. His family story merits a book of its own.

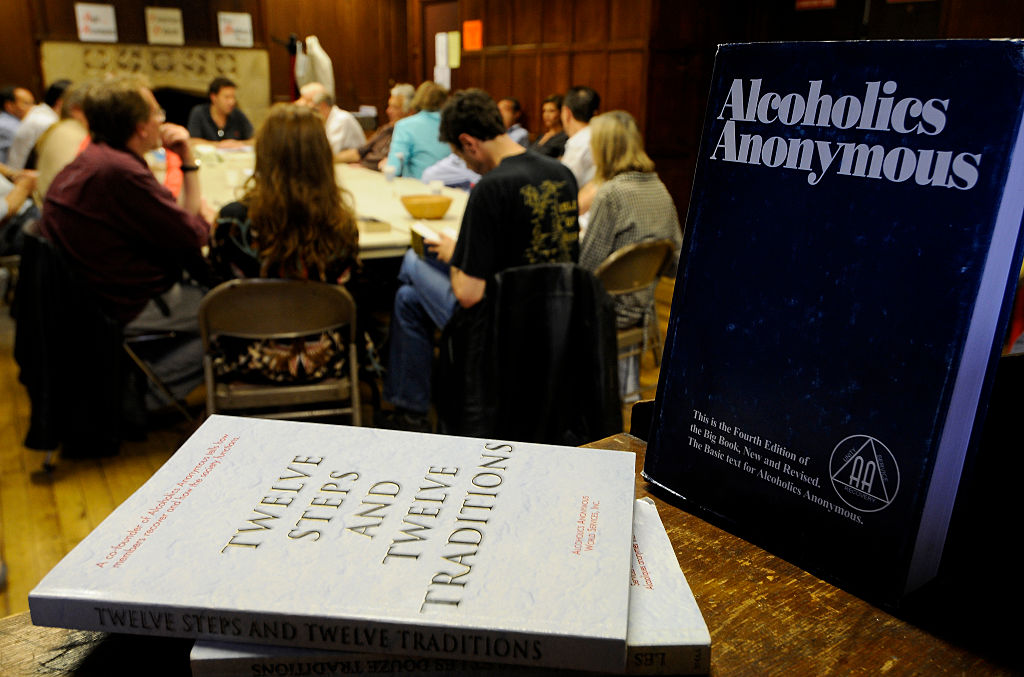

Vuong’s new novel The Emperor of Gladness similarly highlights the author’s past, but expands its focus to a cast of characters who emerge from beyond his shadow. They become so familiar that leaving them at the end of the book feels like a wrench. The story is set in East Gladness, Connecticut, a post-industrial town of veterans and recovering addicts – “if you aim for Gladness and miss, you’ll find us” – where time off is spent blasting Mary J. Blige in empty parking lots.

Winter lasts seven months and the river is a metam-sodium-ridden biohazard. It is into this river that Hai is about to throw himself when the novel begins. His saving grace, in name as in practice, is Grazina: a Lithuanian octogenarian who lives across the bridge and shouts to him just as he is about to jump. An unlikely cohabitation begins.

The junkie, the streetwalker, the idler, the old-timer… they all take their turn in the limelight

As Grazina’s dementia increasingly imprisons her in the frightening years of her youth in Soviet-controlled Lithuania, Hai learns to manage her crises with the help of an imagined American soldier, Sergeant Pepper. These moments, in which Hai subsumes his own pain to take care of Grazina, offer him a way to cope with his misery. The moments that depict the painful process of wrenching Grazina back to the present constitute the novel’s most affecting drama. Yet Vuong chooses to underplay them, which means the reader never fully attains the catharsis that they crave.

Vuong is on surer ground when he describes Hai’s days spent working at HomeMarket, the franchise he joins to fund Grazina’s persistent cravings for frozen Salisbury steak. Here, Vuong has accomplished something noteworthy: he has written the first literary novel featuring the unsung heroes of American fast-food chains, and the result warms the reader with its tenderness. HomeMarket – where it’s Thanksgiving all year round – houses the most compelling ensemble in recent fiction.

We are introduced to BJ, the store’s lesbian manager with WWE aspirations, who takes enormous pride in HomeMarket’s role as “America’s fuel.” There’s Wayne, a specialist in chicken-carving, who alternates banter with regular sips from his pistol-shaped flask. We also meet Maureen, the blonde Midwestern cashier with arthritis and the “foulest mouth you’ve ever heard”; Russia, the Tajikistani boy working to fund his sister’s rehab; and Sony, Hai’s autistic cousin who is obsessed with the Civil War.

These misfits all have their struggles, but Vuong never reduces their difficulties to trauma porn. Many of them are substance abusers, but Vuong’s embrace is capacious – the bigger the character’s vice, the more sensitive their portrayal. In The Emperor of Gladness the junkie, the streetwalker, the idler, the old-timer – those, in other words, who never leave their shitty towns behind – all take their turn in the limelight, unlike their usual fringe existence in the chiefly middle-class domain of the novel.

Vuong hasn’t completely renounced his tendency to interrupt the narrative with the philosophizing tidbits of would-be lyrical flavor which afflicted On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous to an alienating extent. Sometimes the reader is taken aback by lines such as “He was 19, in the midnight of his childhood and a lifetime from first light. He had not been forgiven and neither are you.” These lines feel much like the intrusion of faux-profound poetry in the midst of a serious novel, and can be defined as pretty generalizations packed with a final punch.

Preoccupied as he is with saying something powerfully (whatever that means), the false poet usually ends up saying nothing at all. Vuong’s real strength instead lies in his literary precision. Take this description of the day spent by HomeMarket employees helping Wayne slaughter hogs in view of the Christmas rush: “By the fifth or sixth pig, Hai learned to look not at their eyes, opened too wide, stunned at this terrible gun-wielding god suddenly before them, but at the ears, which, examined closely, resembled a piece of fabric flickering in the breeze. That’s it, that’s what he told himself while pulling the trigger: that he was stapling fabric.” If Vuong may not yet have a distinct literary voice, his powers of observation have improved significantly from his debut.

For all its flaws, The Emperor of Gladness is ultimately a worthwhile novel with a big heart. Its central message is expressed with an allusion to The Brothers Karamazov, when Hai’s mother suggests that hope must persist as long as people are doing “good things for each other.” No matter how great one’s suffering, wherever there is love to give, life is worth living. Vuong brings this humane point home with affecting force.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s June 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply