It was too dark to see, and the painting was upside down.

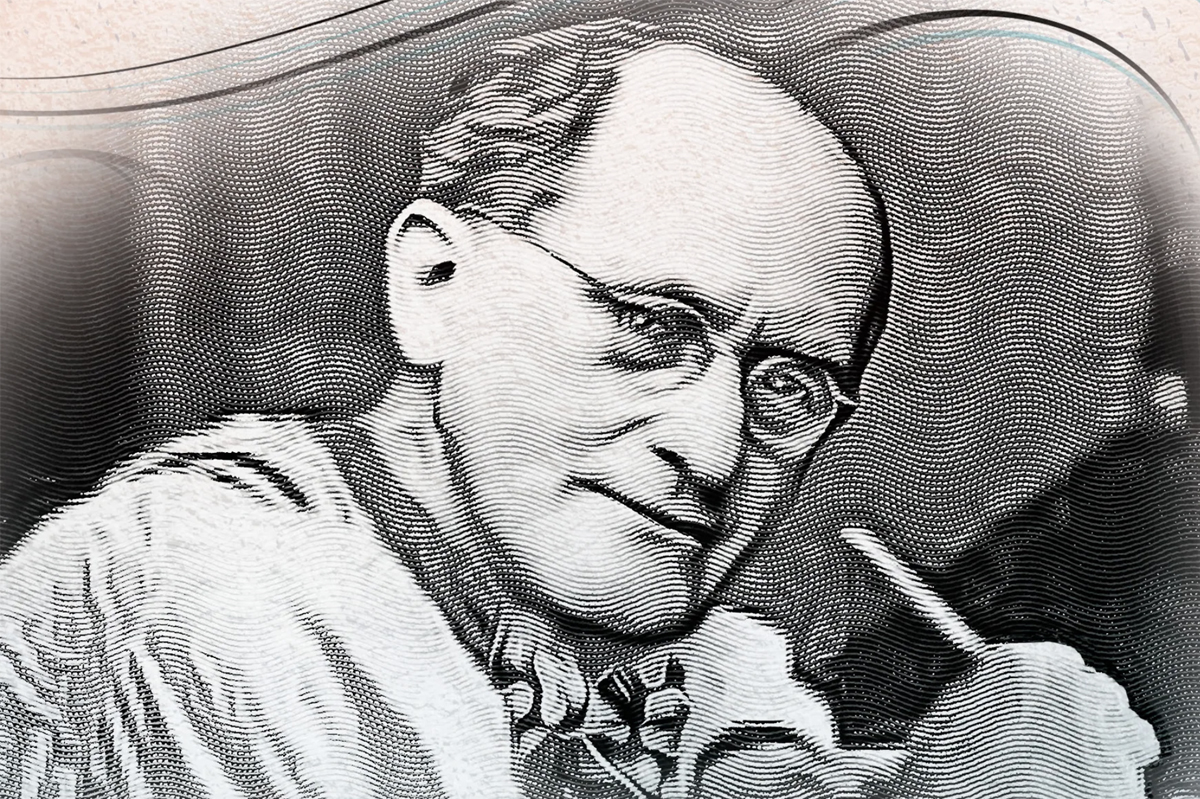

In 1877 John Ruskin, the leading art critic of Victorian England, attended an exhibition that included paintings by the American-born artist James Abbott McNeill Whistler. He hated them — and said so. In print. “I have seen, and heard, much of Cockney impudence before now; but never expected to hear a coxcomb ask two hundred guineas for flinging a pot of paint in the public’s face.” Whistler sued. The following year the argument came to court, on a dark day in a gloomy and gaslit courtroom. The canvases that Ruskin had so disliked were propped up against a wall and barely visible; one was the wrong way up, and another was dropped unceremoniously onto an elderly gentleman’s balding head. Eventually the all-male jury trooped over the road to see the pictures in better light, and so decide whether these were fraudulent daubs or visionary genius.

Ruskin refused to appear. Whistler gave a witty display when cross-examined, claiming he had been libeled, his career and earnings irreparably damaged. The jury found in Whistler’s favor but, contemptuous of the spat, it awarded him a single farthing, which from then on he displayed in determined triumph on a watch chain. Beyond the farce of the courtroom and the gossip of the newspapers, this infamous trial, as Paul Thomas Murphy shows in his terrific book, raised important questions about the role of criticism in art, the boundary between free critical opinion and ad hominem libel and the troublesome early stirrings of “modernism.”

Ruskin had been most incensed by Whistler’s “Nocturne in Black and Gold — The Falling Rocket.” He had made his name defending the luminous experiments of Turner from uncomprehending criticism, but he was outraged by this dark depiction of a fireworks display in a foggy sky. Edging toward abstraction, and influenced by Japanese printmaking, the painting had all the hallmarks of Whistler’s thrilling maturity: an attempt to capture not light but twilight, via a restricted color palette and the use of paint heavily thinned with turpentine (Whistler called it “sauce”). Curls and wisps and speckles of gold are redolent of sparks and smoke, and translucent dabs become figures, barely visible through the mist. Whistler, says Murphy, “surrendered to the darkness… darkness, he discovered, forced abstraction… Other painters of the night clung to the light; Whistler let go.”

He delighted not only in darkness but in paint, simply for being paint, and in the joy of its application, whether in spatters or brushstrokes or washes. This, as the French slogan went, was l’art pour l’art, art for art’s sake, independent of social or even moral function, and in polar opposition to Ruskin’s argument in his seminal Modern Painters: that art should devote itself not to mere aesthetic or sensual pleasure but to the accurate documentation of nature and the imaginative expression of truth. For Ruskin, whose religious doubts never dented his fundamental belief in the divine, this meant God’s truth. As Murphy has it: “Art for God’s sake, or for the soul’s.” The trial at this book’s center stands for something larger than a critic’s dislike of a painting: it is an exploration of opposing ways of seeing, even when it is nearly too dark to see.

Murphy has fun conjuring Whistler, who combined genius with stubborn eccentricity as he struggled for recognition and money (the court case essentially bankrupted him). His life was a tumult of mistresses, illegitimate children and loss of temper. On page twenty-two alone, he manages to insult an editor in print, have a punch-up with a friend and push his brother-in-law through a plate-glass window. I loved the account of guests waiting for him to emerge as he finished one of his “noisy” baths (the mind boggles) or of dinner parties at which he served green-tinted mashed potato (the better to match the china) and chicken that had been puréed and then dyed a vivid magenta. Accepting a commission to decorate a sunny dining room and already in trouble for overspending, he got carried away, painting the room a dark blue before lavishly muraling the walls with gold peacocks.

It is a mark of Murphy’s sympathy for Ruskin that Whistler doesn’t steal the show. But Ruskin had a little touch of Whistler in him: when his mother died, he had her coffin painted sky-blue. Lost in the violent and lunatic ravings of a breakdown, he believed the devil had appeared to him in the form of a peacock. And through it all he wrote and wrote, publishing in total more than nine million words with an ease foreign to Whistler (who was forever scraping his canvases clean and beginning again).

Murphy rightly foregrounds (some of) these words’ significance and influence. Modern Painters was followed by his encomium to the individualism of Gothic, The Stones of Venice, and by the subscription newsletter to the workmen of England, Fors Clavigera, in which appeared the fatal line about the “pot of paint.” Ruskin’s conviction that the political and social health of a culture is in direct relation to its artistic output — that a corrupt culture produces bad art — seems as relevant today as his environmentalism.

In an ideal world this book would have better-quality paper, more illustrations and fewer misprints (“mist” really can’t become “must” in a book about Ruskin and Whistler). There’s a tad too much special pleading: Murphy makes free with “likely,” “surely,” “must have” and, over twenty times, “almost certainly.” An introduction, too, would have helpfully set out in advance the book’s structure and parameters. It takes a while to work out that as many as a hundred pages will be spent narrating the lives of the two men prior to Ruskin’s attack on Falling Rocket: a chapter on one, a chapter on the other. The effect, both before and after the trial, is of flicking between two separate books, a problem compounded for Murphy by the fact that, like Elizabeth I and Mary Queen of Scots, his warring subjects never met. His account of Ruskin begins with boyhood, but for some reason Whistler arrives full-grown and is less knowable in consequence, his childhood in America, and adolescence in Russia, all but omitted.

But there is so much to admire here. That this story is “untold” (as the dust jacket suggests) is a claim to be taken well-salted, but Murphy makes rich use of a recently digitized trove of Whistler’s correspondence, and his piecing-together of the trial itself, from dozens of contemporary newspaper reports, is a tour de force. He has an enviable ability to distill Ruskin’s complex works into a few elegant and lucid paragraphs and has managed to fashion something beautiful and gripping out of the usually dogged process of artistic creation. He trusts in his material, never resorting to the desperate quasi-novelistic biographical style that no good novelist ever dreams of using. (“John Ruskin, his blue eyes staring out above his aquiline nose, his leonine mane swept back from his large forehead, shivers in disbelief as he stares at Whistler’s tenebrous tints…”) And Murphy has humor, never losing sight of how silly great men can be. I laughed, more than once.

“Who won Whistler v. Ruskin?” he asks, concluding “Neither did. Or rather, both did.” Yes. Whistler unleashed a radiantly muted beauty that resonated down the ages. The painting of his mother, properly titled “Arrangement in Grey and Black No. 1,” is in the world’s consciousness. He thinned not only his paint but the border between the figurative and the abstract, sending up a rocket whose sparks landed in Monet’s late water lily murals; in the canvases of Kandinsky and Mondrian and the Abstract Expressionists. Not for nothing did Howard Hodgkin — who claimed never to have painted an abstract in his life — title one of his blazing pictures (icy stripes of foaming blue above a horizon of burning ochre) “After Whistler.” After Whistler, it was different.

But where is Ruskin, now? This book conveys what Murphy calls his “seraphic” prose, and the radical nature of his conservatism, which formed a socialist vision for the future by looking back at a rose-tinted past. He saw the clouds above him darkened and rended by the belchings of “two hundred furnace chimneys in a square of two miles on every side of me.” But what he called the “plague cloud,” with its early intimation of a climate in crisis, was a psychological condition too, a twilight that stained the mind as well as the heavens and caused periods of breakdown and madness. Even when stable he found the murk of the winters at his Lake District retreat all but intolerable. Seasonal Affective Disorder, yes, but also (his term) a pathetic fallacy: a projection of human emotion onto the natural world, a metaphor for his dark and even hallucinatory obsession with Rose La Touche, a cherished pupil whom he had idolized and loved since she was nine, and who died before she was thirty, in a Dublin nursing home.

Even in a diatribe, Ruskin is visionary, as insightful as vicious. Insightful, perhaps, because of the viciousness, in which he took wicked delight: “I’m nearly done toasting my bishop,” he writes of a hapless cleric whose views he had taken against. “He just wants a turn or two, and then a little butter.” The hot buttered toast of his disparagement was more than thoughtless dismissal (“my three-year-old could have done that”). Condemning Whistler for “flinging a pot of paint in the public’s face,” he foresaw what was to come, not least Jackson Pollock’s “drip” paintings of the late 1940s, and the “black pourings” that followed. Disdaining Whistler’s musical titles — “nocturne,” “symphony,” “harmony” — Ruskin wrote: “The public would at once recognize the coxcombry of a composer… who offers them a symphony in green and yellow.” Just two decades after Ruskin’s death, Arthur Bliss would compose A Colour Symphony, its four movements titled “purple,” “red,” “blue” – and “green.”

Given his defense of Turner’s experiments with light, with near-abstraction and ostensibly unfinished canvases, Ruskin’s inordinate dislike of Whistler can be hard to explain or justify. But it seems to me to stem from the fact that Whistler, through his attempt to paint no light, but rather darkness visible, was confronting Ruskin with the plague cloud that so intensely frightened him. This book shows one man embracing fog, and another fleeing it. In Ruskin’s diary, Murphy says, “the same refrain appears, day after day: ‘Black Fog.’” It was the Times of London critic who, attempting witticism and accidentally hitting on truth, described Whistler’s portraits as “materialized spirits and figures in a London fog.” Ruskin saw that the world was a darkling plain, that London was smoky with a new mist, man-made. Murphy: “The world, he realized, was growing darker — but there was a moral component of that physical darkness, as there was, for Ruskin, in all physical things.”

Ruskin v. Whistler; representation v. abstraction… Time often reveals a versus to be an ampersand. Now the smoke of the fireworks has cleared, it is not too dark to see that, from opposed standpoints, Ruskin and Whistler converge in their foggy vision, and their vision of fog. Here is Ruskin: “The sky is covered with grey cloud; — not raincloud, but a dry black veil which no ray of sunshine can pierce; partly diffused in mist, feeble mist, enough to make distant objects unintelligible…” And here Whistler, lecturing in London: “And when the evening mist clothes the riverside with poetry, as with a veil… and the poor buildings lose themselves in the dim sky…”

At the end of his autobiography, Praeterita, Ruskin recounts a trip to Siena and a memorable cloudy twilight.

…the fireflies among the scented thickets shone fitfully in the still undarkened air. How they shone! moving like fine-broken starlight through the purple leaves. How they shone! through the sunset that faded into thunderous night as I entered Siena three days before… the openly golden sky calm behind the Gate of Siena’s heart… and the fireflies everywhere in sky and cloud rising and falling, mixed with the lightning, and more intense than the stars.

“Still undarkened air” — so different from “sky that was still light.” Defending Whistler at the trial, the artist Albert Moore claimed that Whistler’s great and extraordinary achievement was “that he has painted the air.” Ruskin had painted fireflies, Whistler fireworks, each rendering the darkening air in a nocturne of black and gold.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s February 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply