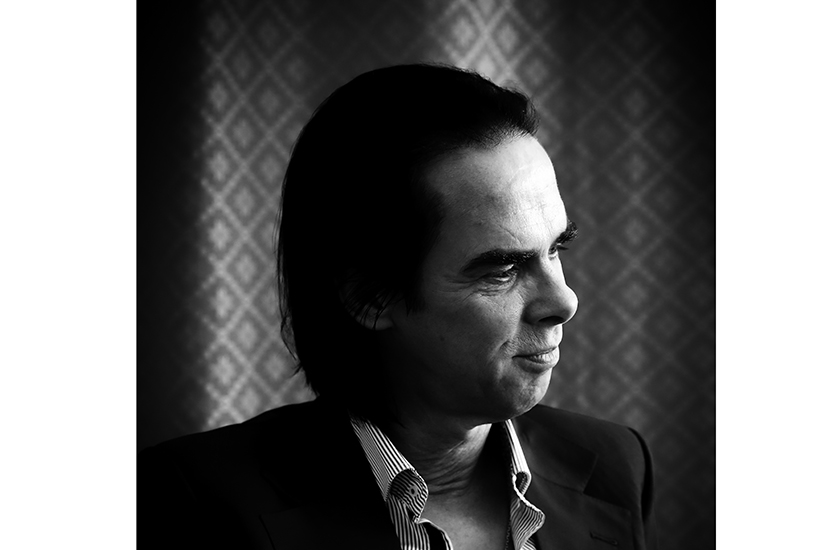

Two years ago the songwriter Nick Cave told his fans that they could ask him any question they liked, and that he’d reply. ‘No moderator’, he wrote. ‘This will be between you and me.’ We’re used to seeing people at their hateful worst online. The Red Hand Files shows them at their best. Cave’s answers deserve an even wider audience, so here below is a selection, chosen by Nick Cave for The Spectator. Considering human imagination the last piece of wilderness, do you think AI will ever be able to write a good song?

Peter, Ljubljana, Slovenia

Dear Peter, In Yuval Noah Harari’s brilliant book 21 Lessons for the 21st Century, he writes that artificial intelligence, with its limitless potential and connectedness, will ultimately render many humans redundant in the work place. This sounds entirely feasible. However, he goes on to say that AI will be able to write better songs than humans can. He says, and excuse my simplistic summation, that we listen to songs to make us feel certain things and that in the future AI will simply be able to map the individual mind and create songs tailored exclusively to our own particular mental algorithms that can make us feel, with far more intensity and precision, whatever it is we want to feel. If we are feeling sad and want to feel happy we simply listen to our bespoke AI happy song and the job will be done. But I am not sure that this is all songs do. Of course, we go to songs to make us feel something — happy, sad, sexy, homesick, excited or whatever — but this is not all a song does. What a great song makes us feel is a sense of awe. There is a reason for this. A sense of awe is almost exclusively predicated on our limitations as human beings. It is entirely to do with our audacity as humans to reach beyond our potential. It is perfectly conceivable that AI could produce a song as good as Nirvana’s ‘Smells Like Teen Spirit’, for example, and that it ticked all the boxes required to make us feel what a song like that should make us feel — in this case, excited and rebellious, let’s say. It is also feasible that AI could produce a song that makes us feel these same feelings, but more intensely than any human songwriter could do. But, I don’t feel that when we listen to ‘Smells Like Teen Spirit’ it is only the song that we are listening to. It feels to me that what we are actually listening to is a withdrawn and alienated young man’s journey out of the small American town of Aberdeen (a young man who by any measure was a walking bundle of dysfunction and human limitation), a young man who had the temerity to howl his particular pain into a microphone and in doing so, by way of the heavens, reach into the hearts of a generation. We are also listening to Iggy Pop walk across his audience’s hands and smear himself in peanut butter while singing ‘1970’. We are listening to Beethoven compose the Ninth Symphony while almost totally deaf. We are listening to Prince, that tiny cluster of purple atoms, singing in the pouring rain at the Super Bowl and blowing everyone’s minds. We are listening to Nina Simone stuff all her rage and disappointment into the most tender of love songs. We are listening to Paganini continue to play his Stradivarius as the strings snapped. We are listening to Jimi Hendrix kneel and set fire to his own instrument. What we are actually listening to is human limitation and the audacity to transcend it. Artificial intelligence, for all its unlimitedpotential, simply doesn’t have this capacity. How could it? And this is the essence of transcendence. If we have limitless potential then what is there to transcend? And therefore what is the purpose of the imagination at all? Music has the ability to touch the celestial sphere with the tips of its fingers and the awe and wonder we feel is in the desperate temerity of the reach, not just the outcome. Where is the transcendent splendor in unlimited potential? So to answer your question, Peter, AI would have the capacity to write a good song, but not a great one. It lacks the nerve.

Love, Nick

***

What do you think of cancel culture?

Frances, Los Angeles, USA

Dear Frances, Mercy is a value that should be at the heart of any functioning and tolerant society. Mercy ultimately acknowledges that we are all imperfect and in doing so allows us the oxygen to breathe — to feel protected within a society, through our mutual fallibility. Without mercy, a society loses its soul and devours itself. Mercy allows us the ability to engage openly in free-ranging conversation — an expansion of collective discovery toward a common good. If mercy is our guide we have a safety net of mutual consideration, and we can, to quote Oscar Wilde, ‘play gracefully with ideas’. Yet mercy is not a given. It is a value we must nurture and aspire to. Tolerance allows the spirit of enquiry the confidence to roam freely, to make mistakes, to self-correct, to be bold, to dare to doubt and in the process to chance upon new and more advanced ideas. Without mercy society grows inflexible, fearful, vindictive and humorless. Frances, you’ve asked about cancel culture. As far as I can see, cancel culture is mercy’s antithesis. Political correctness has grown to become the unhappiest religion in the world. Its once honorable attempt to reimagine our society in a more equitable way now embodies all the worst aspects that religion has to offer (and none of the beauty) — moral certainty and self-righteousness shorn even of the capacity for redemption. It has become quite literally, bad religion run amok. Cancel culture’s refusal to engage with uncomfortable ideas has an asphyxiating effect on the creative soul of a society. Compassion is the primary experience — the heart event — out of which emerges the genius and generosity of the imagination. Creativity is an act of love that can knock up against our most foundational beliefs, and in doing so brings forth fresh ways of seeing the world. This is both the function and glory of art and ideas. A force that finds its meaning in the cancellation of these difficult ideas hampers the creative spirit of a society and strikes at the complex and diverse nature of its culture. But this is where we are. We are a culture in transition, and it may be that we are heading toward a more equal society — I don’t know — but what essential values will we forfeit in the process? Love, Nick

***

Do you enjoy magic? Card tricks, stage illusions, that kind of thing.

Richard, London, UK

Dear Richard, Yes, I do have an interest in magic, or at least I used to. My boy Arthur became obsessed with it when he was about 13 and for a year, maybe more, all he did was magic. Every day he sat around shuffling cards and flipping coins, and watching endless online magic tutorials and DVDs by his favorite magicians. He joined The Young Magicians Club at The Magic Circle and I would drive him around to magic shows and magicians’ conventions and trade shows and magic shops. He practiced and practiced and became really good at it. In the summer of 2014, in Los Angeles, we spent much of our time down on Hollywood

Boulevard watching the street magicians, and Arthur would show them his magic tricks and they would show him theirs. We hung out at the Magic Castle every Saturday that summer, and entered this strange community of magicians, who taught Arthur the Classic Pass and the Double Turnover and the various coin tricks, and Arthur got so good at sleight of hand it seemed that there was nothing he couldn’t make disappear.

Our dear friend Larry ‘Ratso’ Sloman, who wrote the definitive book on Harry Houdini, introduced us to the great David Blaine — we went to his house and Arthur showed him a couple of his tricks and David called Arthur ‘a good magician’, then took out a deck of cards and completely blew our minds. Later on he gave Arthur the novel Siddhartha by Hermann Hesse, which Arthur never read, but kept next to his bed.

Then one day, back in Brighton, Arthur just stopped doing magic completely. I asked him why and he just shrugged and said, ‘I don’t want to do it any more, Dad’, and that was the end of that — and, I suppose, the end of my active interest in magic, too.

Richard, I hope I’ve answered your question. I am sorry that maybe in the end these words are not addressed to you. Maybe these words are projected beyond this world, as a wish, as a prayer, as a sleight of hand, hoping they may draw the attention of the spirits themselves. Our boy, our magician, our vanisher — we miss you.

Love, Nick

[special_offer]

What is your view on the BBC decision on censorship of certain words in ‘Fairytale of New York’ last Christmas?

Joseph, The Hague, Holland

Dear Joseph, Truly great songs that are as emotionally powerful as ‘Fairytale of New York’ are very rare indeed. ‘Fairytale’ is a lyrical high-wire act of dizzying scope and potency, and it rightly takes its place as the greatest Christmas song ever written. It stands shoulder to shoulder with any great song, from any time, not just for its sheer audacity, or its deep empathy, but for its astonishing technical brilliance. One of the many reasons this song is so loved is that, beyond almost any other song I can think of, it speaks with such profound compassion to the marginalized and the dispossessed. With one of the greatest opening lines ever written, the lyrics and the vocal performance emanate from deep inside the lived experience itself, existing within the very bones of the song. It never looks down on its protagonists. It does not patronize, but speaks its truth, clear and unadorned. It is a magnificent gift to the outcast, the unlucky and the brokenhearted. We empathize with the plight of the two fractious characters, who live their lonely, desperate lives against all that Christmas promises — home and hearth, cheer, bounty and goodwill. It is as real a piece of lyric writing as I have ever heard, and I have always felt it a great privilege to be close friends with its creator, Shane MacGowan. Now, once again, ‘Fairytale’ is under attack. The idea that a word, or a line, in a song can simply be changed for another and not do it significant damage is a notion that can only be upheld by those that know nothing about the fragile nature of songwriting. The changing of the word ‘faggot’ for the nonsense word ‘haggard’ destroys the song by deflating it right at its essential and most reckless moment, stripping it of its value. It becomes a song that has been tampered with, compromised, tamed and neutered and can no longer be called a great song. It is a song that has lost its truth, its honor and integrity — a song that has knelt down and allowed the BBC to do its grim and sticky business. I am in no position to comment on how offensive the word ‘faggot’ is to some people, particularly to the young — it may be deeply offensive, I don’t know, in which case Radio 1 should have made the decision to simply ban the song, and allow it to retain its outlaw spirit and its dignity. In the end, I feel sorry for ‘Fairytale’, a song so gloriously problematic, as great works of art so often are, performed by one of the most scurrilous and seditious bands of our time, whose best shows were so completely and triumphantly out of order, they had to be seen to believed. Yet time and time again the integrity of this magnificent song is tested. The BBC, that gatekeeper of our brittle sensibilities, forever acting in our best interests, continues to mutilate an artifact of immense cultural value and in doing so takes something from us this Christmas, impossible to measure or replace. On and on it goes, and we are all the less for it. Love, Nick For more of Nick Cave’s answers, see www.redhandfiles.com. This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the US edition here.