I don’t think anyone has ever come up with a word to describe an authorized author. It’s not quite a tautology. The writer, who has been invited to write a novel continuing the body of work of another, might, possibly, be an example of literary parthenogenesis. Or, more pejoratively, karaoke.

Who knows? But either way, it’s a growth industry. You will have seen the new authorized James Bond novels, the recently crafted Miss Marple and George Smiley outings that have appeared on the bookstore shelves over the past few years to some fanfare – despite the fact that those characters’ creators are very much pushing up the daisies. No, the mortality status of said celebrated novelists is no barrier – perhaps it’s even an incentive – to fans of the series rushing out and handing over their cash for the work featuring their favorite sleuth or spy.

In those cases, the literary estate of Ian Fleming, for instance, will have authorized the new book in return for a cut of the proceeds. But sometimes – perhaps more strangely – the originators are alive and kicking but don’t fancy another ten months in front of their laptop, and so they subcontract the work. Hence, Lee Child can still introduce his latest smash-hit Jack Reacher thriller to a hungry readership, without hiding the fact that the actual words were written by his brother Andrew. Either way, the arrangement leaves everyone content and fulfilled.

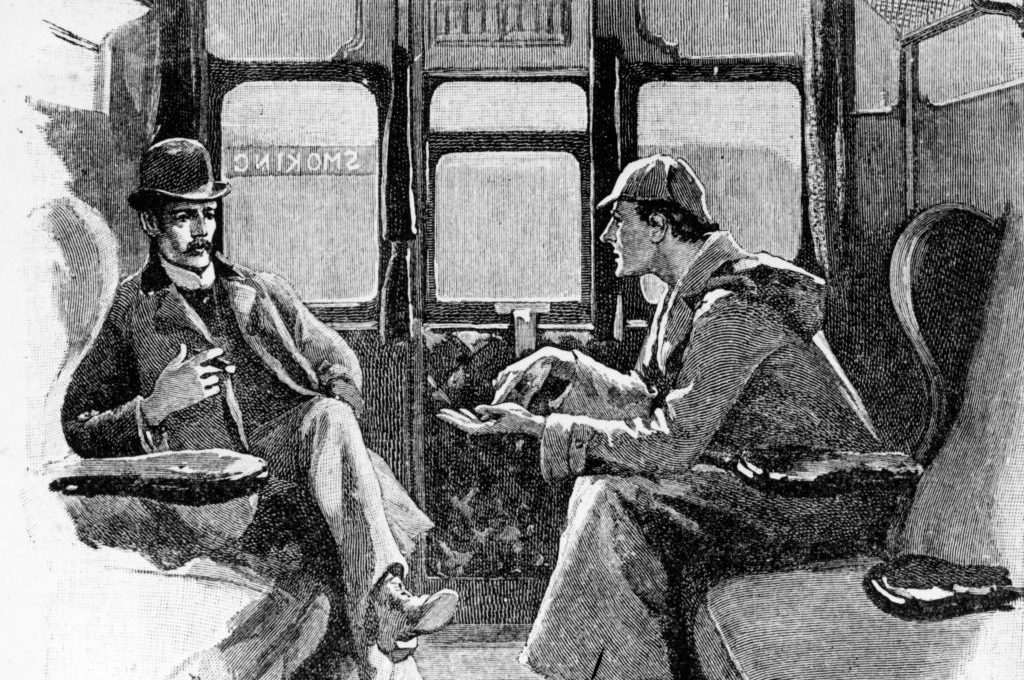

I know whereof I speak. When it was announced that the Conan Doyle literary estate had authorized me to write a new Sherlock Holmes novel, the first question I was publicly asked was whether I thought I was up to the job. After all, Holmes is a uniquely popular character, listed in the Guinness World Records as the most-portrayed human literary creation, with hundreds of films and television shows about him. But I do, as it happens, think I’m up to it. I wouldn’t have written it otherwise, would I?

Holmes and Moriarty was published in the US this past May, with near-simultaneous publication in a wide range of European countries. My literary agent, Jon, came up with the idea. He had previously published the last two authorized Holmes novels, written by Anthony Horowitz, and was therefore in touch with the Conan Doyle estate, made up of Sir Arthur’s descendants. They were interested in finding a new author to continue their ancestor’s legacy, and my previous Gothic-tinged Victorian-set mystery, The Turnglass, had been a Sunday Times bestseller, so they wanted to know what I would do with Holmes.

My answer was to open up his world a little more. The longest Conan Doyle novel about Holmes, The Hound of the Baskervilles, is a touch under 60,000 words. Today, the standard intelligent thriller is 100,000. That disparity is a blessing and a curse. The blessing is that it gives you a lot of room for expansion – Holmes is a gripping character, but there’s little depth to him in each individual story. That can be augmented. And so can his world, so that the new book can be more of a narrative story, less of a puzzle with a bit of action thrown in. It can change, twist and turn, develop.

The curse is that it has to be these things. If I write 100,000 words in which there is no light and shade to Holmes, nothing new about Watson and the puzzle that exercises our hero’s brain is the beginning and end of the world that he inhabits, it will become tedious somewhere around the 30,000-word mark. The reader will either slog on with increasing impatience and decreasing enjoyment or throw the book over his shoulder and move on to the new Robert Harris novel.

But most of all, if you are a “continuation author” you need a hook, a unique selling point for the fans that can be expressed in the single clause of a single sentence. Here we go: “Holmes and Moriarty are forced to work together on a case.” Eleven words. Excellent. And then, while it sinks in, give it a little color. “An astonishing and deadly menace threatens to destroy both these colossuses of crime and all they hold dear, leaving them with no choice but to collaborate. But can they navigate the tensions and suspicions that follow or descend into mutual treachery?”

Enough punch? Let’s hope so, because then you can get into the nitty-gritty of why you write this book: the surprising fact that Moriarty only appears in person in a single Holmes story (“The Final Problem”) and so we desperately want to see more of him, to explore his dark mind and motivations.

Then there’s the writing itself. I don’t write precisely like Conan Doyle. My sentence structures, my imagery, characterizations, plot preferences and experiences of London life all differ from his, not least because I’m writing a century after he died. Any attempt to copy his writing as closely as humanly possible results in that dreadful word, “pastiche,” rather than expansion. It’s also got a few touches of comedy, not least my enlargement of the character of Colonel Sebastian Moran. In the Conan Doyle canon, Moriarty’s arch henchman speaks little and shoots often. I interpret him as a swaggering bullyboy with a chip on his shoulder about working for the unimposing professor: such touches are fun to play with.

“But isn’t it contrary to the canon to have some gags?” demand the nitpickers. Nope. Conan Doyle – and Holmes himself – liked the odd jape. Holmes thoroughly enjoyed spooking Watson by appearing before his chum in disguise or ribbing him about his reputation as a ladies’ man. And the author wrote the odd bit of roister-doister comedy, not least in the one or two very short Holmes stories that he wrote almost as parodies of own tales, “How Watson Learned The Trick” and “The Field Bazaar.”

How far can you, the continuation author, go in putting your own stamp on things? Well, there are limits – guardrails, as we have to call them in today’s parlance. You don’t want the character’s fanbase to dislike it, because you need them for the all-important word-of-mouth recommendation. Nor do you want the horrified literary estate to take one look at your first draft and cancel the whole deal. The likelihood, though, is that you’re also a fan, though, so you have little desire to write something utterly outside the canonical style. In other words, I could have written a Holmes and Moriarty rom-com – with Watson as Cupid – or a post-Baskervilles slasher horror where detective turns into werewolf, but I didn’t want to, and the estate wouldn’t have allowed it to be published. And if it had, no one would have bought it.

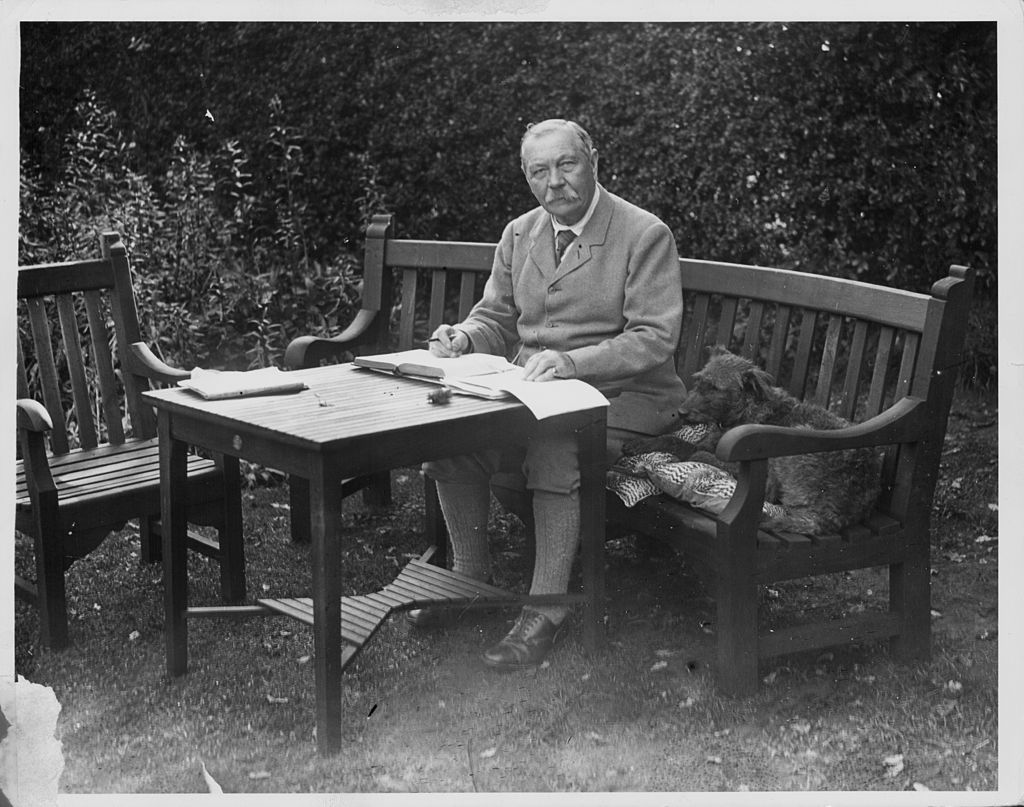

When it comes to changing social mores, meanwhile, there are some attitudes and remarks by Holmes and other characters that seem fairly old-hat now, but we don’t need to impose any positive discrimination to make up for it. Least said, soonest mended, as the detective’s Victorian brethren believed. And yet, a worry niggles. In writing a continuation novel in the style of Arthur Conan Doyle, am I anything more than an analogue version of ChatGPT? Can I do anything that the artificial intelligence can’t – or, at least, won’t be able to do in five years’ time?

Tricky one, isn’t it?

Wrestling with the question, out of curiosity, I asked the program to write a short Holmes tale about my dog. Admittedly, the story didn’t include the most astounding mystery, but it was quite readable, and in plausible Conan Doyle style. “What one man can invent, another can discover,” Holmes states in “The Adventure of the Dancing Men.” Well, quite. So what can I add? What is the point of an author when AI programs can scan and ingest every word ever written?

The answer is that, while their voracious appetite for data appears unlimited, this is an illusion. They can swallow every recorded word, from English to Sanskrit to Celtic runes, but they can never gather the data of organic experience, which is, unlike everything that has been written, non-sequitous and unpredictable. As such, there is never the essential spark of creativity that comes from lived and indefinite experience; it can only ever be feigned.

What’s the value of genuine creativity over pretended creativity? It is the same value as reading fiction itself: it’s a part of humanity that we enjoy and prize despite it having little superficial utilitarian value. It represents a certain defiant flourishing of the human spirit. Conan Doyle loved the mysteries of the universe. His much-discussed spiritualism was, I think, not at odds with the thought process of his scientific materialist detective, but complementary to it. Both knew that there was something more out there, that the superficial and predictable was to be discarded.

There is now another human, Gareth Rubin, at work adding to Conan Doyle’s work. The final product will be the imperfect, unpredictable, rough-around-the-edges novel that you get when organic experiences froth up with a century-venerable canon. A twist, you say. I hope, should this inside-baseball account not put you off entirely, that you’ll enjoy reading it as much as I relished creating another adventure for Holmes, Watson and the others.

Leave a Reply