Crossing streets with lattes in hand, camera lights flashing, perfectly curated outfits meant to be noticed, and a crisp chill in the air means one thing: New York Fashion Week has arrived.

The September Fashion Week has long stood as the pinnacle of American fashion prestige. As the leaves turn red and brown, style photographers capture eclectic ensembles in motion, A-listers march through the streets and assistants carefully place nameplates on front-row seats beside pristine runways. But this year the week’s shimmer feels noticeably dimmed.

The big names still show up – Michael Kors, Calvin Klein, Tory Burch. But in recent years they’ve been eclipsed by smaller, edgier and distinctly New York-based designers. You may not have heard of KidSuper, Private Policy or Elena Velez, or ever worn their clothes, but they run the show now. Luxury and haute-couture designers are just not interested in New York.

Why? Because New York Fashion Week has evolved into a content-driven machine – designed less for insiders and more for the camera and the internet. Outside every venue, photographers offer built-in photo ops. Inside, every runway look is instantly broadcast across social media. And the after-parties? They’re engineered for virality, not intimacy, with every detail curated to be posted.

Take the party hosted by Valentino Beauty, for example, promoting its new Rendez-Vous Ivory fragrance. Styled as a revival of Studio 54 – the legendary nightclub and theater that launched the disco craze – the event featured multiple branded locations where guests could pose with products. The whole thing felt less like a nostalgic homage or reinvention and more like a giant, immersive ad campaign. Cher made an appearance, but the night was no tribute to old New York. It was a made-for-Instagram marketing opportunity.

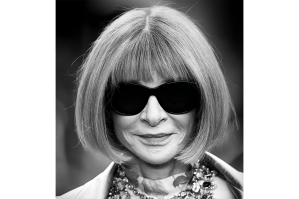

On the runways themselves, the front-row seats once reserved for the fashion industry’s power-players are now set aside for online influencers and content creators. A-list celebrities and arbiters of style such as Anna Wintour used to consistently own these seats. Today, they’re more populated by influencers such as Paige Lorenze, Brigette and Danielle Pheloung, and Ken Eurich. Never heard of ’em? Don’t worry – all you need to know is that their combined Instagram followings total around 2.8 million. All this is meant to make NYFW seem more accessible. As the stylist Sophia Isabella told me: “The reason brands invite influencers to their shows is to have this pseudo-concept of accessibility while also maintaining the old habits and rituals of exclusivity in fashion.”

This points to a new, unstable tension. Social media has made it incredibly easy to compare our daily lives with those of influencers and public figures – people who feel relatable, except for one key difference: disposable income. This ease of comparison has fueled a culture of unsatisfiable trend-chasing and consumerism, as audiences try to emulate the lifestyles they see online. But aspiration and exclusivity have always been the core drivers of the high-fashion industry – even for those who believe they’ve gained access to it. No amount of pseudo-accessibility can change that, at least not without stripping high fashion of what makes it high.

Many brands have begun to recognize this – too much accessibility has done them no good. In response, many luxury labels are starting to pull back and become even more exclusive. They’re going “offline” and departing from old staples, such as NYFW. Rather than letting any influencer with a few hundred thousand followers into their events, they’re curating their shows even more carefully and exclusively than they did before.

Many are decamping to Paris, where influencers and social media are given less power. These Parisian events resist the hyper-glossy, social-media-ready structure of New York Fashion Week. This resistance pushes back against the homogenizing force of the internet and social media, which flattens everything it touches in its mission to make everything relatable and accessible. As the rest of the world becomes more connected and leveled, the savviest high-fashion houses are retreating further into intentional inaccessibility – that’s why they’re avoiding the limelight in New York.

These elite houses – chief among them the Row, Proenza Schouler and Willy Chavarria – are bringing elitism, allure and mystery back into fashion. And they’re perhaps restoring high fashion to what it was always meant to be: an aspirational art, one that compels its aspirants to earn a place in elite society.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s October 13, 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply