The resignation of Jim Ryan as president of the University of Virginia in June marks the growing momentum of the Trump administration’s efforts to dismantle diversity, equity and inclusion initiatives within US universities. The Department of Justice deemed Ryan’s resignation a step toward resolving its inquiry into UVA’s compliance with the administration’s new policies. Conservatives may be encouraged by news of major institutions like UVA and Harvard rolling back heavy-handed DEI programming. But pure reactionary animus to the excesses of progressive ideology has often gotten conservatives into trouble – not just in education, but in the arts. We need only look to 2023, when a teacher at a classical school in Florida was fired after parents complained he was exposing their children to “pornography” – photos of Michelangelo’s “David”.

Yes, DEI has led to hideously ideological exhibitions in museums that aim to indoctrinate viewers with empty identity politics, usually under the guise of “amplifying the voices of minorities.” Museums that kowtow to the progressive ideology du jour diminish their own credibility as institutions charged with preserving artistic patrimony. But challenging DEI’s hegemonic grasp is not simply an opportunity to revel in a blind reactionary spirit. Rather, it is an opportunity to forge an alternative approach to platforming a wide array of works of art – one which doesn’t aim to threaten traditional values, but serves to bolster them.

Museums that kowtow to the progressive ideology du jour diminish their own credibility

A recent exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art comes to mind. The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism set out to explore “the comprehensive and far-reaching ways in which black artists portrayed everyday modern life” during the Harlem Renaissance. The exhibition featured painting, sculpture, photography, film and ephemera that shed light on Harlem’s vibrant black enclaves between the 1920s and 1940s. It included pieces that captured the period’s intercultural exchanges, such as Palmer Hayden’s French-style floral still-life that featured a bouquet of lilies alongside an African tribal mask.

Also included were portraits of “African diasporan subjects” by Europeans such as Matisse, Munch and Picasso. The exhibition closed with a final wall-length panoramic collage of the various happenings on a Harlem block, including a creative Afrocentric rendering of the Annunciation to the Virgin Mary as it occurs inside an apartment building bedroom.

“Blackness,” for the exhibit’s curators, seemed less an “identity category” than a cultural legacy – one with deep roots and sense of tradition passed down from generation to generation by particular communities. The museum’s platform, used to promote diversity in this case, avoided the cloying tropes that demonize white people and even gave space to the role that religion, family and self-reliance played in building up Harlem’s black enclaves.

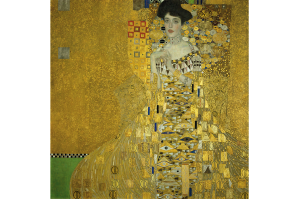

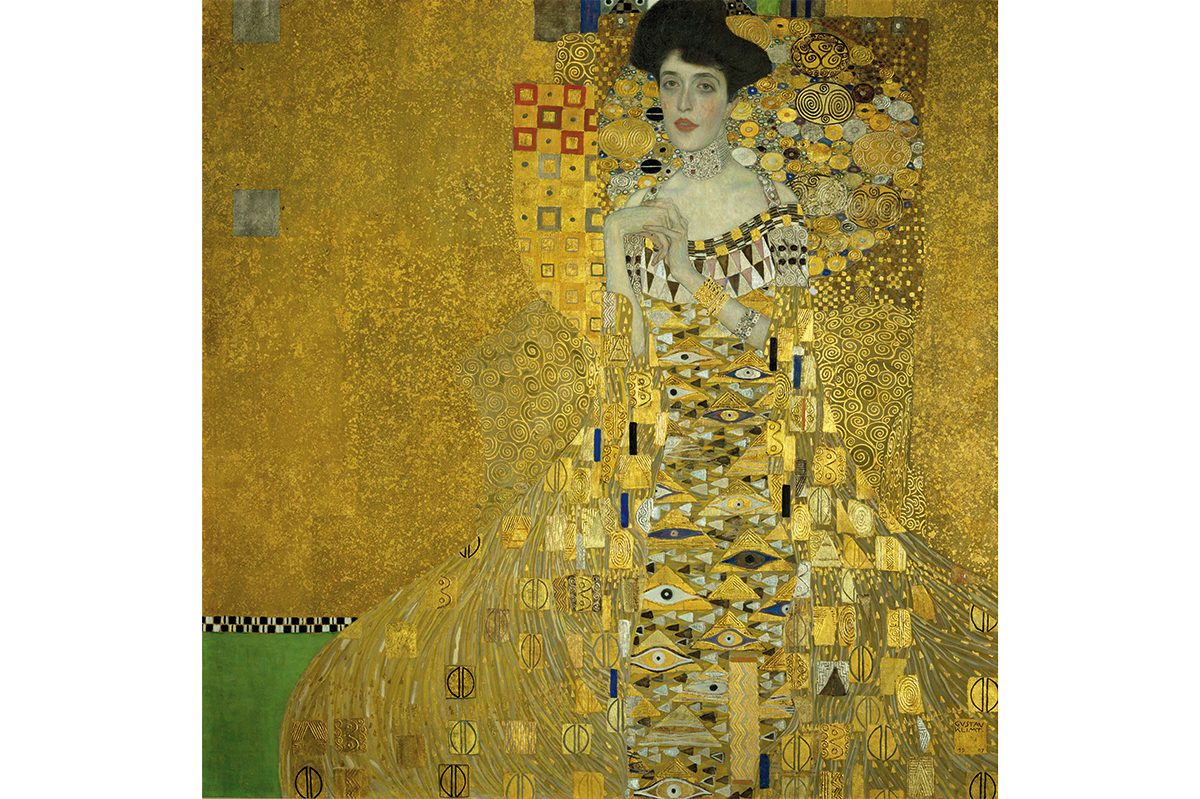

Most importantly, the pieces of art on display were inherently beautiful in themselves, like Aaron Douglas’s impressionistic paintings inspired by Old Testament stories and Winold Reiss’s emotive depictions of black fathers with their children enshrouded by gold leaf. This is one of many examples where exhibitions have centered the art of minority groups with the purpose of exploration rather than preaching, including the Met’s past exhibitions on Arturo Alfonso Schomburg and Juan de Pareja and on Byzantine iconography found in Africa; the Smithsonian American Art Museum’s Pictures of Belonging: Miki Hayakawa, Hisako Hibi and Miné Okubo; and the short film May the Lord Watch, which is being screened at Museum of Fine Arts Boston.

These experiences for the viewer are a far cry from what so many other museums do these days: treat diversity as an ideological identity category to be checked off.

Take the notorious Brooklyn Museum, known for its discombobulated curation, which tends to place more emphasis on the caption accompanying each piece than the art itself. The curation at recent exhibitions like Toward Joy: New Frameworks for American Art is over-reliant on academic jargon that comes off as preaching, without attempting to feign objectivity. This approach to diversity uses art as a tool to indoctrinate viewers with progressive ideology.

It is also patronizing to the minority communities whose cause they claim to champion. Self-righteous posturing distracts from the artistic contributions of the communities they are featuring. The exhibition is largely an opportunity for the institution’s stewards to pat themselves on the back.

While visiting a collection of pre-Columbian indigenous artifacts in a museum in Chile, author Patrick Deneen remarked that he couldn’t help but wonder about “the causes of the extinction of these once-vibrant and self-perpetuating cultures.” Surely colonialism and natural disasters played their part, but he also pointed out how the push for “diversity and inclusion,” rather than affording more agency to cultures around the globe, has propagated a globalizing monoculture that neutralizes “actual diversity – biodiversity, financial diversity (i.e., local markets) and educational diversity in the name of local, regional, religious and pedagogical traditions.”

Contrary to the insistence of identitarian ideologues, diversity is not a good in itself. Nor does it have to be a threat to traditional values. Conservatives in the art world should look to the example of those attempting to forge a space for greater diversity within classical education, such as Angel Adams Parham, Anika T. Prather and proponents of ethnopolitics like Daniel Patrick Moynihan, Geno Baroni, Camille Paglia, and Michael Novak who understood how to promote diversity within the context of traditional values.

In an age when culture is being overtaken not just by unimaginative ideologies, but by screens and the onslaught of AI, we need art that keeps our collective imagination and sense of tradition alive. This must not exclude minority voices: rather, it should create a renewed sense of diversity that preserves the ideals inherited from the past and adapts them to ensure a sustainable future.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s August 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply