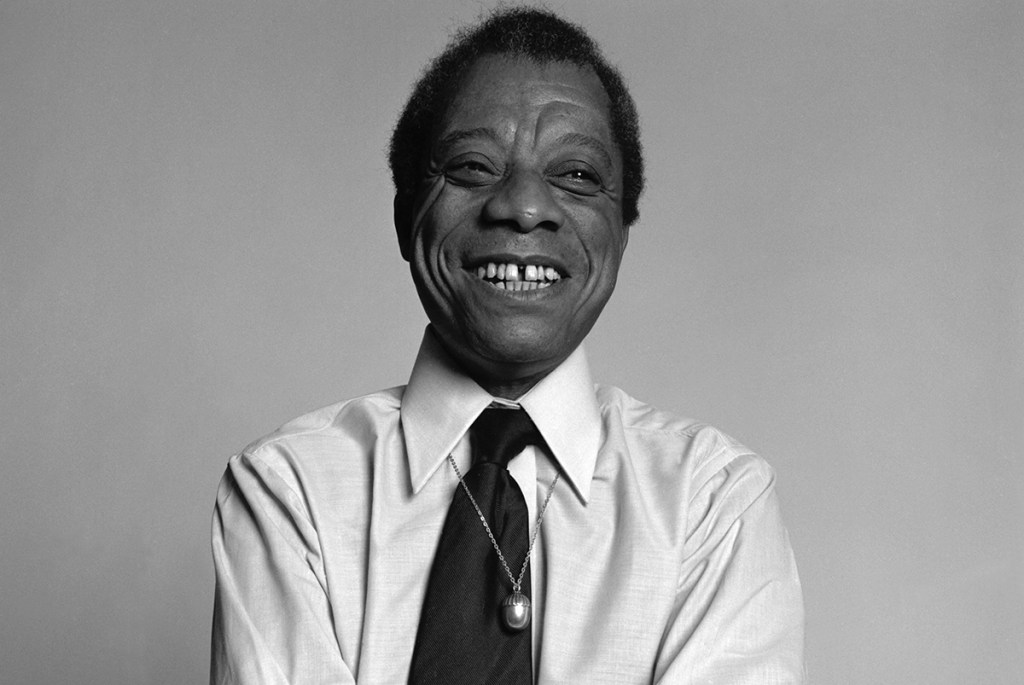

James Baldwin never wanted to be a symbol, but became one anyway: a stand-in for defiance, for beauty, for pain wrapped in elegance and for the entire weight of a country’s unresolved sin. Baldwin didn’t just write about America – he exposed it: the good, the bad and the ugly. He told the truth, even when it hurt. He didn’t soften the edges.

What he never quite got, in his lifetime, was intimacy on the page about his own life. Biography existed around him, but he was rarely at the center of it. If we see him now, we see a man who smoked too much, drank too much and who sometimes ran from both his lovers and himself – rather than what he was: an intangible literary icon. Nicholas Boggs tries, in Baldwin: A Love Story, to give us a more rounded picture of the author. It’s first major biography of Baldwin in more than 30 years.

Baldwin didn’t believe in fixed categories because he understood that labels are traps

The book’s most effective thread is Baldwin’s lifelong tension with America. He loved his country but also felt disgust with it. He wished to rescue it from itself. That’s where Boggs shines. He doesn’t sanitize Baldwin’s rage, but he also doesn’t ignore his inherent contradictions. Baldwin could write blistering critiques of white America, then turn around and say, “I never really managed to hate white people – though, God knows, I have often wished to murder more than one or two.” That line wasn’t rhetorical. It was born of experience, which encompassed both years of brutal racism, but also encounters like the one with Orilla Miller, a white teacher who recognized his brilliance when others saw a black boy to be condemned and contained. “Bill,” as he called her, gave him books. Through them, she granted him entry to a world where no one else thought he belonged. And she gave him just enough faith in humanity to keep writing to it, instead of turning his back on it entirely.

Baldwin could hold fire, fury and forgiveness in the same breath, and Boggs captures that brilliance when he lets Baldwin speak for himself. But then comes the problem – and it’s a big one. If there’s a fatal flaw in his approach, it’s his unnecessary embrace of contemporary identity politics. It is a depressing urge to drag a complex, incandescent figure through the narrow corridors of 21st-century categorization, and to retrofit modern terminology onto a man who spent his entire life rejecting exactly that kind of reductive thinking. It’s not just misguided – it’s selfish. And it does Baldwin a profound disservice.

This isn’t some minor literary quibble. It’s a fundamental betrayal of Baldwin’s core philosophy. The man who wrote “Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced” understood that true change requires honest confrontation with complexity, not the comfort of simplified categories.

Though he is often described as a gay man, Baldwin never referred to himself that way. He didn’t like the word, just as he despised labels of any kind. He was a man who loved other men – openly, hungrily – but also had serious relationships with women. He rejected the notion that sexuality had to be pinned down, catalogued or explained to satisfy other people’s often prurient need for neatness. Near the end of his life, in essays such as “Here Be Dragons” and “To Crush the Serpent,” he made his position explicit: love isn’t about sex or gender. It’s about the person. He didn’t believe in fixed categories because he understood that labels are traps – limiting, reductive and antithetical to the full complexity of human experience.

Baldwin wasn’t trying to hide who he was. He just refused to be defined using someone else’s terms. And yet here comes Boggs, decades later, determined to do exactly that. The author can’t resist the anachronistic lure of categorization. He writes about Baldwin as if he were some kind of proto-nonbinary figure, a forerunner to today’s alphabet soup of identity markers. There’s a desperate quality to it, as if Boggs is trying to make Baldwin more palatable to a generation that can’t understand a person without first slapping a label on them. It’s the height of intellectual arrogance. Baldwin spent his life fighting against this very impulse; now Boggs wants to conscript him into today’s identity wars. It’s absurd.

This generational selfishness runs deeper than mere historical revisionism. Today’s activists and academics seem incapable of allowing historical figures to exist on their own terms. Everything must be filtered through the lens of contemporary grievance and struggle. Baldwin becomes not a singular voice who carved out his own path through impossible circumstances, but a blank check for whatever movement wants to cash in on borrowed gravitas. It’s cultural grave-robbing dressed up as scholarship.

Consider what Baldwin actually said about identity: “I am not your negro.” Not “I am not a negro,” but “I am not your negro.” The distinction matters. He wasn’t rejecting his blackness or his sexuality; he was rejecting other people’s right to define what those things meant for him. He understood that every label comes with a set of expectations, a script to follow, a role to play. And he refused to perform for anyone’s comfort.

The transgender movement’s bewildering attempt to claim Baldwin as an early pioneer is particularly galling because it represents exactly the kind of thinking he spent his life opposing. When he wrote about love transcending gender, he wasn’t making a political statement about pronouns or bathroom rights; he was pointing out the inadequacy of language to contain the full spectrum of human experience.

Baldwin understood that once you let people define you, you lose control of your own narrative. He knew that labels become prisons. The lifestyle choices he embraced were dangerous. He wasn’t celebrated for them, but exiled, as well as being dismissed, threatened and attacked. When Giovanni’s Room was ready for print in the mid-1950s, his publisher begged him to reconsider. A black author writing a novel about white men conducting a gay love affair was commercial suicide. Baldwin published it anyway, because he believed in the power of storytelling. This was a story that needed to be told, even if it destroyed his career.

In trying to rescue Baldwin from historical erasure, the author ends up erasing him all over again

Baldwin lived through an era when being different could get you killed. There were no pride parades, no corporate sponsorships, no academic departments dedicated to his “experience.” Baldwin wasn’t fighting for representation; he was fighting for the right to be left alone to do his work. He didn’t want to be a symbol for gay rights or black liberation or any other cause. He wanted to be a writer, period. The fact that his existence challenged social norms was incidental to his larger purpose.

The deeper irony is impossible to ignore: in trying to rescue Baldwin from historical erasure, Boggs ends up erasing him all over again. It’s exactly the kind of thinking Baldwin warned us about – the reduction of human complexity to political utility.

This is what happens when biography becomes advocacy. Instead of letting Baldwin speak for himself – which he did, extensively and brilliantly – Boggs feels compelled to translate his words into contemporary terminology, as if the man who wrote Notes of a Native Son somehow needs a 21st-century interpreter to make him relevant. The hubris is breathtaking.

What’s particularly frustrating is that Baldwin’s actual words on identity and categorization are readily available and unambiguous. He didn’t speak in code or hide his feelings behind euphemism. When he rejected labels, he did so explicitly and repeatedly. In interviews, essays and novels, he made clear that he saw fixed categories as fundamentally dishonest – a way of avoiding the hard work of actually seeing and understanding individual human beings.

On the whole, Baldwin: A Love Story is a frustrating mixed bag. It could have been exceptional and important, but it isn’t. At his best, Boggs reminds us that Baldwin’s voice still matters and his insights still cut deep. When the book slows down, when it stops genuflecting to contemporary sensibilities and lets Baldwin speak, it succeeds. The tenderness is real, and occasionally moving. These moments reveal what the book might have been: a portrait of Baldwin as a man wrestling with his demons, his contradictions, his impossible love for an impossible country. But the political preening guts it all, leaving us with a book that drifts between personal confession and ideological diary, revealing more about the author’s sympathies than about the real Baldwin.

There are better biographies. David Leeming’s 1994 James Baldwin: A Biography remains essential and far more honest, treating Baldwin as a complete human being rather than a collection of modish talking points. But Boggs offers something others haven’t: an intimacy that feels sincere, even when it’s misguided.

This isn’t the definitive Baldwin biography. It’s the one written not from distance, but from love. The problem is that love, when filtered through ideology, can become just another form of distortion. When you love someone so much that you can’t bear to let them be themselves, you end up changing them into what you need them to be. That’s what Boggs has done here – and the results are a heartfelt disappointment.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s September 15, 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply