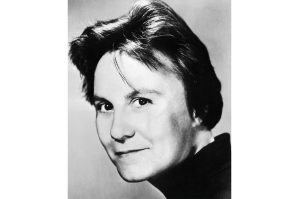

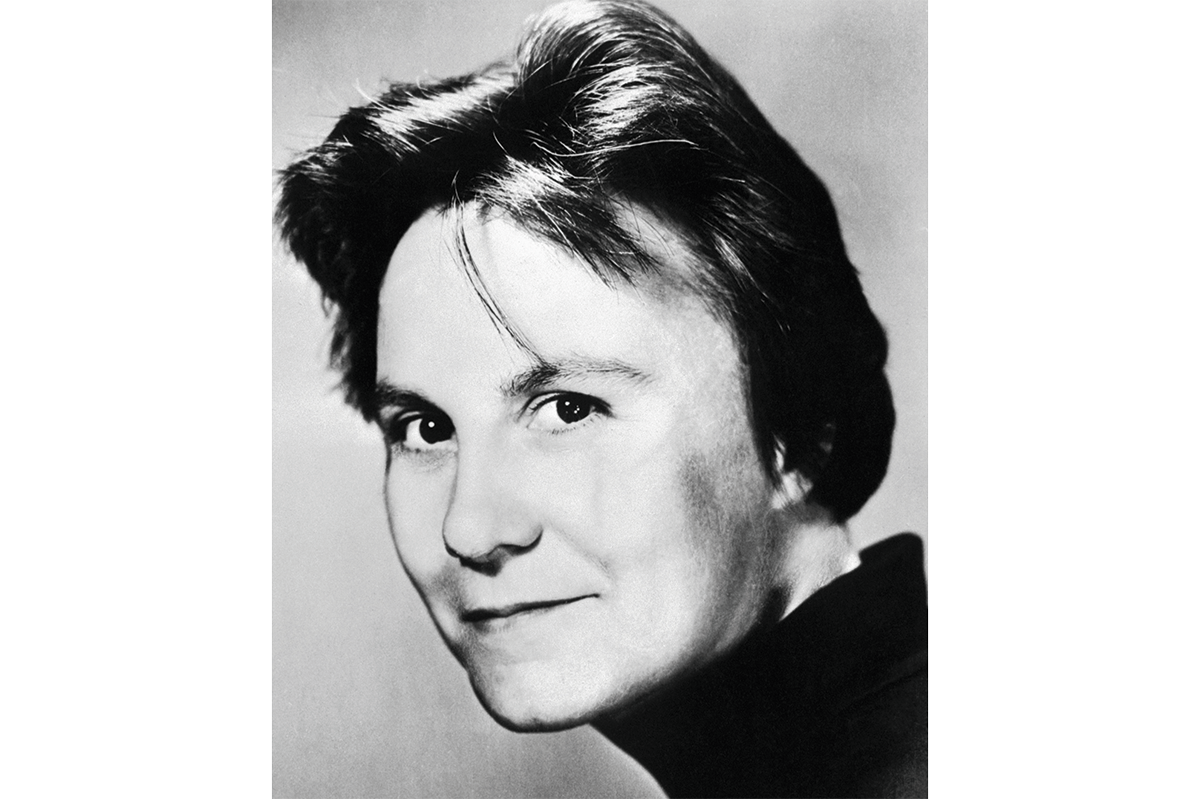

In his adopted city of San Francisco, the poet, publisher and painter Lawrence Ferlinghetti is venerated to levels nearing those of patron sainthood. In 1954, he co-founded the bookshop-cum-press City Lights on Columbus Avenue, which cleaves North Beach from Chinatown on the top right tip of the San Franciscan peninsula.

Lauded by the Los Angeles Times as the man ‘without whom the Beat generation might not have found its voice’, Ferlinghetti is perhaps best known for having published Allen Ginsberg’s generation-defining Howl (and subsequently being arrested for, then cleared of, obscenity charges). But he also published others, such as Gregory Corso and Jack Kerouac. His bookshop became a focal point for that rag-tag bunch which came to be known as the Beats, those black-clad bad boys of bepop and mezcal, a club with ‘no begetting of children’ and no small sampling of the death wish.

Little Boy (the release of which has been timed to coincide with Ferlinghetti’s 100th birthday on March 24 — at time of writing he is still alive), is an experimental novel ‘with no plot’ and memoir of a life ‘whose plot is only discovered after it is lived’. Not a promising start. If it weren’t quite so un-hip, one might call it auto-fiction. The intention appears to be a whistle-stop tour of the century he’s lived, ending in our current age of ‘steel and smog and plastic’. No news there, except historical backdrop is largely absent, and the narration flips between the first and third pronoun — he is Little Boy, Little Boy is ‘me me me’. A few pages in, full stops are completely renounced, which made reading it a rather breathless experience, but also deeply boring.

There are puns well into the realm of dad jokes (‘let us prey’; ‘amen and awomen’; ‘Mao Tse-Tung or mouse say-tongue and the Chinese revolution Mao say tongue-in-cheek’). There are the predictable preoccupations with Hamlet and a dated reliance on Freud. Buddhist terminology is sprinkled gratuitously; there’s a repetitive eulogizing of Jack Kerouac (and the ‘American innocence’ for which he apparently stood) which feels more like name-dropping, and lots of talk about his penis. If it feels out of fashion, it’s because Ferlinghetti is.

‘So I’m a broken record or a human tape loop,’ Little Boy tells us flippantly, preempting my complaints, ‘And this ain’t no novel.’ No, it isn’t. These pages are the junk notes of someone who sat in a café people-watching and never actually started writing. It’s a missive from a living fossil: he can remember the Depression; he is of the generation whose ‘birthing day’ was December 7 1941; a generation who toured European universities on the G.I. Bill and had minds blown by this new-fangled thing called existentialism. He is at best a mediocre poet, famous for his aiding and abetting of greater ones; a midwife to the finest minds of his generation; and a historical mooring. He is not one of the giants on whose shoulders we stand, but he did give some people a leg up.

This article was originally published in The Spectator magazine.