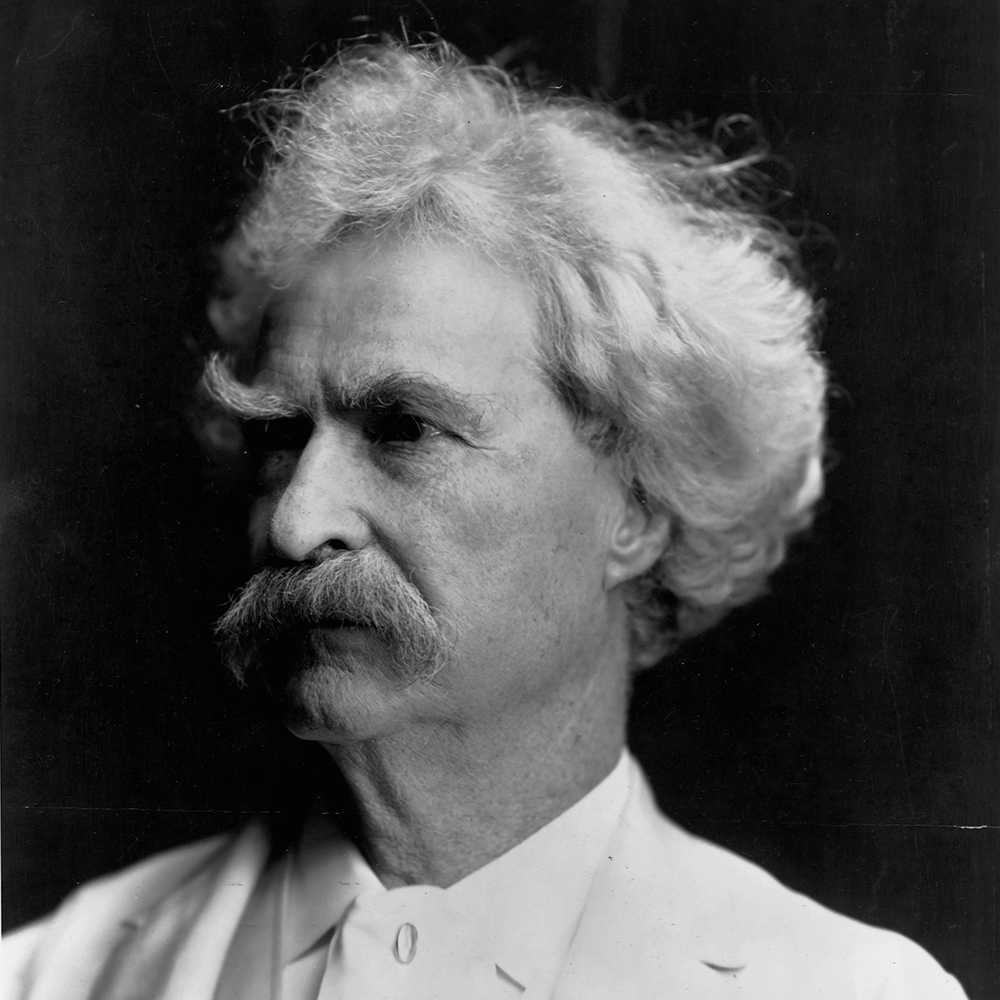

To speak of Mark Twain is to speak of the American psyche laid bare: forever restless, with an insatiable appetite for reinvention and biting commentary. Twain was not just a novelist or humorist: he was, in many respects, the nation’s most accurate mirror. He wrote the truth and then laughed at it. He carved his stories out of riverbanks and war zones, courtrooms and campfires. In his storytelling, Twain blurred the lines between truth and falsehoods, rage and laughter, freedom and fate. He gave us some of the greatest figures in American fiction. But Twain (1835-1910) was a creation more vivid, more volatile and more enduring than any character he put on the page.

The “father of American literature,” as William Faulkner called him, didn’t hide behind his fiction. Instead, he bled into it. The man born Samuel Langhorne Clemens made himself the raw material. “The periodical and sudden changes of mood in me, from deep melancholy to half-insane tempests and cyclones of humor, are among the curiosities of my life,” Twain once wrote.

To attempt a definitive biography of such a man is an audacious act. To succeed at it is something closer to a literary creation in its own right. Ron Chernow’s Mark Twain, a work of overwhelming ambition and painstaking control, is precisely that. Not only is it the most exhaustive portrait of Twain ever written, it is perhaps the most psychologically intimate.

Twain was not just a novelist or humorist: he was the nation’s most accurate mirror

Chernow does not merely track Twain’s movements, he examines his moods, compulsions, long silences and sudden eruptions. He maps the fault lines between performance and despair, charting how Twain’s public genius was often built atop private fractures. Over more than a thousand pages, Chernow identifies the emotional root system that fed Twain’s art and haunted his life. Crucially, the biographer of Washington, Hamilton, Grant and John D. Rockefeller brings to Twain the same blend of forensic precision and narrative elegance that defines his other work.

He started to use the name Mark Twain in 1863. As Twain, he might be a printer, pilot, gold-seeker, lecturer, humorist, publisher, investor, failure and international celebrity. His genius defied containment. He wrote The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, a novel Chernow says is “perhaps the greatest antislavery novel in the English language.” He was also shaped by a town where black servitude and white sentimentality uncomfortably coexisted. Twain looked back on that world, and on the people who molded him, with both honesty and sorrow. He wrote of his mother that, “kind-hearted and compassionate as she was, I think she was not conscious that slavery was a bald, grotesque and unwarranted usurpation. As far as her experience went, the wise, the good and the holy were unanimous in the belief that slavery was right.”

These contradictions were inherited and deeply internalized. Twain sought to escape them, yet also, artistically speaking, to drag them forward. As Chernow writes, “From unpromising beginnings, Twain’s striking evolution in matters of racial tolerance will be traced throughout this book.” So they are.

From this seedbed of cognitive dissonance grew a writer who would go on to finance the education of a black law student, denounce Belgian King Leopold’s reign of terror in the Congo and produce some of the most sympathetic portrayals of the black community in American fiction. The novelist William Dean Howells called him “the most de-southernized Southerner I ever met.”

This biography traces, step by step, the intellectual and moral journey that earned that praise. But Chernow shows us the battle for Twain’s progressive credentials, too. His empathy didn’t stem from theory, but memory. The voices of enslaved people from his childhood – their stories, their songs – remained in his mind long after he left Missouri. Yet Twain never quite became the radical he might have been. His notorious unpublished essay, The United States of Lyncherdom, which Chernow discusses with great delicacy, opens with Twain in the odd position of defending Missouri’s character before turning on the sordid spectacle of Southern lynchings.

The piece, brimming with bitterness and sardonic fury, was too dangerous to publish in his lifetime. Afraid of alienating Southern readers and friends, Twain suppressed it. As Chernow notes, he was a man who essentially had two sets of opinions. (The remnants, perhaps, of the Clemens-Twain duality.) As Twain noted: “I suppose that in more cases than we should like to admit, we have two sets of opinions: one private, the other public; one secret and sincere, the other corn-pone and more or less tainted.” It’s a pattern Chernow documents repeatedly: Twain would draft ferocious essays – on slavery, on religion, on the corruption of democracy – only to shelve them.

Sometimes publishers recoiled. But more often than not, Twain censored himself. He craved truth, but he also desired adoration and applause. He railed against the herd, yet dreaded being ostracized. Chernow doesn’t regard this as cowardice, but the cost of playing both jester and prophet in the public square. To speak too plainly risked ridicule, while to entertain too easily dulled his edge. Twain occupied a unique and often lonely place between those two extremes. The author knew what should be said. He just wasn’t always willing to say it aloud.

The same friction coursed through Twain’s personal life. His fierce love for his wife Livy stands in contrast to his fixation on teenage girls after her death. These “angelfish,” as Twain called them, were never touched inappropriately, but the emotional and erotic charge he projected onto them is difficult to ignore. Although his longing was wrapped in paternalism, it was laced with a desire for something purer, younger, less complicated. It remains, at best, troubling. That same impulse that led to such unsettling fixations led to reckless financial decisions as well

Nowhere does Chernow’s exhaustive method prove more valuable than in his account of Twain’s finances. He digs into the entrails of every disastrous venture, from the doomed Paige typesetting machine, which Twain convinced himself would revolutionize printing, to his lavish spending on a publishing house that hemorrhaged cash while he stubbornly kept it afloat. A man who consistently mocked fraudsters and con artists in his fiction was one of their most predictable victims in life. That self-destructive streak drew him into bankruptcy, public disgrace and ultimately an exhausting global lecture tour to settle his debts.

Chernow chronicles these missteps not to shame Twain, but to uncover the deeper engine behind them. In truth, these tours were acts of survival. Twain was bankrupt, emotionally empty and adrift in middle age when he took to the global stage. But night after night, continent after continent, he summoned charisma from fatigue, turning exhaustion into enlightenment. He joked about imperialism in Melbourne, insulted royalty in Vienna and wept over his lost loved ones in private between shows. The Twain who had brought houses down with his tales of jumping frogs was the same man who, alone in his hotel, read Livy’s letters until the ink blurred.

When he returned home and saw the aged faces of childhood friends, he glimpsed the ghost of his own past

Twain’s finest invention, Chernow argues, was not Tom Sawyer, Huck Finn, or the mischievous Connecticut Yankee. It was, in fact, himself. The white suit, the wild hair, the sardonic wit – these weren’t mere peculiar quirks but armor. Twain the persona allowed Samuel Clemens the man to survive. Behind the stagecraft he was racked by existential angst, rage and self-doubt. The mask didn’t just protect Twain from the world, it protected him from himself. Every room he entered, every lecture hall he commanded became a canvas for his performance art, where his laughter and outrage disguised the tremor underneath.

This becomes heartbreakingly evident in Chernow’s account of Twain’s grief. The death of his daughter Susy in 1896 nearly destroyed him. The loss of Jean, his youngest, in 1909, five years after Livy’s death, shattered what was left. By the time Twain entered his final years, he wasn’t writing to entertain or provoke; he was, it seems, writing to survive. His later works, including The Mysterious Stranger and Letters from the Earth, have an almost apocalyptic tone. With great patience and considerable care, Chernow lingers on these gathering storms, tenderly tracing the darkness that blanketed Twain’s final years. The departure of his nearest and dearest, the disintegration of friendships and the inevitable isolation of old age all took their toll. They chipped away at both the man and at the myth he had created.

Once celebrated for his defiance and irreverence, Twain came to view his younger self with a mix of awe, regret and, at times, disbelief. When he returned to his hometown and saw the aged faces of childhood friends, he saw his past staring back at him. “There was so much old joy and newfound sorrow locked up inside him,” Chernow writes, “that he constantly trembled on the edge of tears.” The stage, which had once given Twain control over the narrative, seemed to amplify his loneliness. Even in packed halls, among the most devoted and loving fans, he remained estranged from the one thing he longed for most: being a barefoot boy on the banks of the Mississippi, chasing riverboats, blissfully unaware of the weight he’d one day carry.

And yet even his death had something wondrous about it. Twain said in 1909 that “I came in with Halley’s Comet in 1835; it’s coming again next year, and I expect to go out with it. It would be a great disappointment in my life if I don’t. The Almighty has said, no doubt: ‘Now here are these two unaccountable freaks; they came in together, they must go out together.’” He was not disappointed. He died on April 21, 1910, when the comet was at its nearest to the sun; a cosmic reminder, perhaps, that greatness blazes, even until the end.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s August 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply