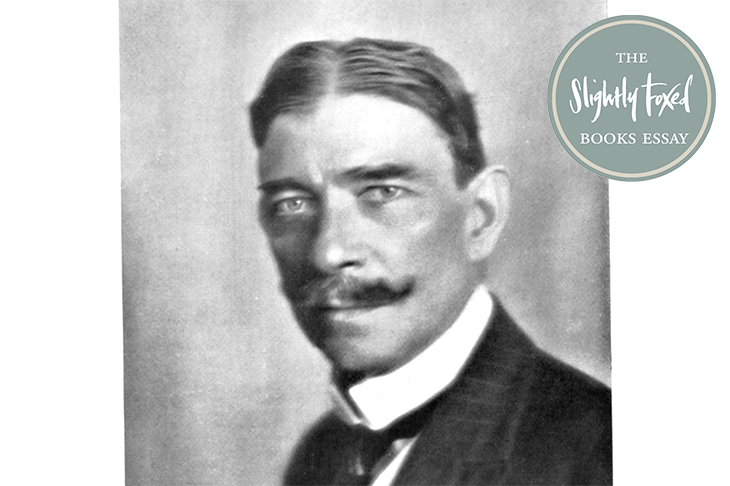

Does anyone today know who Frank Harris was? Are his novels and biographies read at all now? A hundred years ago he was acknowledged ‘by all great men of letters of his time to be . . . greater than his contemporaries because he is a master of life’, or so wrote the critic John Middleton Murry. George Meredith likened his novels to Balzac’s, and Bernard Shaw his short stories to Maupassant’s – high praise which was somewhat deflated by the discovery that one story had actually been lifted from Stendhal. But no one would have been more astonished at his disappearance as a great man of letters than Frank Harris himself. ‘Christ goes deeper than I do,’ he explained, ‘but I have had wider experience.’

I first heard of Frank Harris from the biographer Hesketh Pearson. When he was young he had praised Harris as being ‘the most dynamic writer alive’. This praise diminished over the years and Pearson never wrote a Life of Harris. But Harris made several comic appearances in my biographies. It was difficult to avoid him. There have been half a dozen published Lives of him and he makes many appearances in other writers’ autobiographies. He seems also to have inspired several characters in works of fiction. Ford Madox Ford presented him in The Simple Life Limited (1911) as George Everard, ‘his horrible unique self’. In Frederick Cassel’s novel The Adventures of John Johns (1879), there is a caricature of him becoming editor of a newspaper by seducing the proprietor’s wife. In George and Weedon Grossmith’s The Diary of a Nobody (1897), he appeared as Hardfur Huttle, ‘a man who did all the talking’ and came out with the most alarming ideas. H. G. Wells used him in his science-fiction novel The War in the Air (1907) as Butteridge, ‘a man singularly free from false modesty’ who believes ‘all we have we owe to women’. It is surprising that a man with so many fictional lives seemed to disappear during the late 20th century.

After his death, Harris came to life again in several dramatic roles. He appeared in the film Cowboy, adapted in 1958 from his My Reminiscences as a Cowboy; then, in 1978, he could be seen in a BBC television play called Fearless Frank, played by Leonard Rossiter; and later in Tom Stoppard’s theatre play The Invention of Love. His correspondence with Bernard Shaw was quietly published in 1982. Somehow and somewhere, his exploits were always available.

‘The Connoisseur of Harris’ was Hugh Kingsmill. In 1919 he published a novel called The Will to Love which he had written in a prisoner-of-war camp. Harris appears in it as Ralph Parker, a man whose friendship ‘was a craving for an audience, his love, lust in fancy dress’. Yet ‘in the ruins of his nature, crushed but not extinct, something genuine and noble struggled to express itself ’. Harris was in his seventies when he died in the summer of 1931, and Kingsmill’s biography of him was published the following year. They had known each other for 20 years, and the book was one of those Lives that contain two main characters: the subject and the writer.

Kingsmill treats Harris as a comedian without a sense of humor. He seemed to be two different people, a Robin Hood who robbed the rich to help the poor — and a man determined not to be poor himself. He jettisoned one belief for another, longing for many things he did not want. A born actor was what he appeared to be, someone whose best performance was the noble art of seduction. ‘His praise of sensuality’, Kingsmill wrote, ‘. . . sounded melodiously in the ear of youth, and I hastened to sit at the feet of a master whose message agreed so well with what I desired from life.’

Harris’s mother had died when he was three — and his sister was to instruct him how to attract girls and make a good marriage. Kingsmill described the rules as follows: ‘First, praise the good points of the girl’s face and figure; secondly, notice and approve her dress, for she will think you really like her if you notice her clothes; thirdly, tell her she is unique . . . and finally, kiss her.’ To this Harris was to add ‘the principle of feigned indifference’. He learnt all this so as to overcome his ugliness. ‘I examined myself in a mirror, saw that I was ugly, and never looked at myself again.’ His black hair was thick and low on his forehead, his features were irregular, he had large ears, an energetic chin and, worst of all, he was ridiculously short for a man of action. He tried to offset these disadvantages by developing his muscles until he resembled a prize-fighter. To gain an extra inch in height he used elevators in his boots, and to avoid his overtaxed digestion he made use of a stomach pump. His aim was to get pleasure and avoid its consequences – what Kingsmill described as ‘to eat his cake and not have it’.

Harris did not understand that although men were attracted to women mainly by what they saw, women were more attracted to men by what they heard. Harris’s attraction lay in his voice. He was endowed with a strong, dark, resonant, bass voice used with amazing fluency when he gave public speeches. To his young disciples he seemed the one man who could put the world to rights.

Frank, originally called ‘James Thomas’, had been born at one time or another during the 1850s, perhaps in Ireland, possibly in Wales – all depending on which of his autobiographical writings you read. Kingsmill did not hunt for certainties; he used Harris’s escape from the storehouse of facts as a revelation of his character. ‘He was born uneasy,’ Kingsmill wrote. He hated his time at school where he was bullied by bigger boys and he did not get on well with his father. At the age of 14, with great courage and ingenuity, he set off for America to seek a happier life.

On reaching New York, Harris became a bootblack, a workman in the caissons of Brooklyn Bridge and, arriving in Chicago, a night-clerk at a hotel where he joined a group of cowboys. Somehow his horsemanship enabled him to write on bull-fighting with the knowledge of an expert. He spent some time at Kansas University studying law, and did not return to Europe until his very early twenties, traveling back by several routes. ‘Harris traveling westwards across the Pacific and Harris traveling eastwards across the Atlantic met again in Paris,’ Kingsmill explained.

Back in Britain he was to become the editor of several newspapers and magazines which gave him a prominent place in the literary scene. He began editing the Evening News, giving readers the suggestive and sensational stories he had enjoyed at the age of 14. Kingsmill quotes some of his headlines: ‘Mad Dogs in the Metropolis’, ‘Measles in Church’, ‘Extraordinary Charge against a Clergyman’, ‘Awful Death in a Brewery’. He had the adroitness of a journalist and increased the sales of the papers he edited — The Fortnightly Review, The Saturday Review, Modern Society. But his downfall was sudden, and as complete as his rise had been brilliant and unexpected. This was because he took no notice of what the proprietors wanted. He became discontented with reporting other people’s happenings: he wanted to create happenings himself — especially political happenings. Adventures, he decided, came to the adventurous. He set about becoming a Tory Member of Parliament, marrying a wealthy widow who lived in Park Lane and entertaining politicians and businessmen only to discover he thoroughly disliked them. He was a Tory, it is true, but he was also a socialist and an anarchist.

Kingsmill singled out three subjects of special interest among the biographies Harris wrote: Bernard Shaw, Oscar Wilde and Shakespeare. He wrote about Shaw at the end of his life and his biography was published posthumously. According to Shaw, Harris had ‘an elaborate hypothesis of some fundamental weakness in my constitution’ and it amused Shaw to counteract this with his generosity. Harris ‘was grateful to Shaw for his unbroken friendliness’, Kingsmill wrote, ‘. . . yet resentful at being helped by a man whose success exasperated him’. One of Shaw’s most generous acts was to contribute a chapter to Harris’s Life of Oscar Wilde.

Wilde had initially been repelled by Harris, while Harris was impressed by Wilde’s charm, humor and social success. It was Harris who was to warn Wilde what would happen after Lord Queensberry had been acquitted of criminal libel. He urged Wilde to leave the country at once — a yacht was waiting for him in the Thames. But Wilde seems to have lost his nerve and was, as Harris predicted, found guilty of gross indecency and sent to jail for two years. Harris tried unsuccessfully to get well-known writers to sign a petition for his release and then visited Reading Gaol where he succeeded in getting him more humane conditions. And then he ruined their friendship. He took the plot of a play Wilde had planned and made it his own. He promised Wilde money when he was out of prison — and never gave it to him. And Wilde, who had been in tears at Harris’s kindness, came to the conclusion that he ‘has no feelings. It is the secret of his success.’ Yet Harris had been brave: defending Wilde to the extent that he had to insist he himself was not homosexual — though, he added thoughtfully, ‘if Shakespeare had asked me, I would have had to submit’.

Harris’s Oscar Wilde: His Life and Confessions was published in 1916. The Man Shakespeare and His Tragic Life Story had come out after many years of writing and research seven years earlier. ‘Frank Harris is upstairs,’ Oscar Wilde had written, ‘thinking about Shakespeare at the top of his voice.’ It was probably his desire for fame that first prompted Harris to write about Shakespeare. On some pages he seems to confuse Shakespeare with himself. But his aim was to reveal the man behind the plays — the Victorians who studied the plays having forgotten there was such a man. He had read Georg Brandes’s recent study of Shakespeare, and described it as ‘the ablest of Shakespeare’s commentaries’, though Kingsmill noted that Harris made ‘no acknowledgement of his obvious debt’ to it. Despite Harris’s imperfections, Kingsmill’s book ends with his strengths:

‘The finest passage in his writings is where he passes in review the spokesmen of Shakespeare’s sadness or despair: Richard II sounding the shallow vanity of man’s desires, the futility of man’s hopes; Brutus taking an everlasting farewell of his friend and going willingly to his rest; Hamlet desiring unsentient death; Vincentio turning to sleep from life’s deceptions; Lear with his shrieks of pain and pitiful ravings; Macbeth crying from the outer darkness.’