Down to his chosen name, Man Ray (born Emmanuel Radnitzky in Philadelphia in 1890) worked hard to squash anything about him you might call human. At least that’s what is suggested by the Met’s exhibition Man Ray: When Objects Dream. The show spans much of his career – he was associated with surrealism and dada, held a day job as a commercial photographer and experimented with almost every medium imaginable – but coheres around his so-called rayographs, also known, in less egotistical fashion, as photograms.

Many will know this medium from elementary school: place objects on top of a light-sensitive sheet and expose them to light to yield white silhouettes against a dark background. These and the other works on view are weird and alluring in the way that a sleek, beautiful sociopath is.

The show floats around the artist’s career from about the mid-1910s to the mid-1930s, by which time he had achieved avant-garde stardom. We find mechanistic, brutish paintings of color planes; airbrushed canvases with all the technical shortcomings of a Magritte and little of the charm; cliché-verres of spindly, dancing lines; “primitive” sculptures; a slick chess board; and much more. A mobile of cascading clothes hangers casts a rotating, crystalline shadow on the floor. A pair of 1918-20 photographs titled “L’homme” and “La femme” – an eggbeater and an assemblage including two side-by-side reflectors, respectively – are chuckle-worthy in their anatomical punning but slightly sinister, not least because Man Ray at one point switched their titles. There’s a void at the heart of these works. It’s not that the artist is trying to conceal the artist’s hand; it’s that whatever hand is there isn’t quite human.

The central room holds most of the rayographs, rectangles of rich black hues hung on black walls. The white negative space takes the shape of combs, cones, eggs, nails, the cubic limits of crystal prisms, even two ghostly banjos, fuzzy with translucent drums and rings of reflective chrome. Also displayed here is one of the exhibition’s several films: “Le retour à la raison” (1923), a scattershot series of reverse silhouettes. Most of the reel was developed using the same method as the rayographs, but the images are interspersed with shots including a headless woman’s nude torso. The film reveals that the pictures sometimes work better when they flash by quickly rather than when they linger. What’s striking about the rayographs is that they look as if they were made by someone who doesn’t quite know what household objects are used for – or who wants to make everyone else forget. Q-tips, matches, a wing bolt attached to a screw – we can no longer recognize them by their utility, let alone imagine picking them up. Each object is hollowed of its purpose; only outline remains. As each object’s human ends are washed away, so too is its essence.

The exhibition’s insight is in linking the rayographs to the other realms of Man Ray’s oeuvre: the curators, Stephanie D’Alessandro and Stephen C. Pinson, make clear that this was all conceived by the same mind. Exit the rayograph galleries and take a look at the infamous “Cadeau” (1921), a flatiron with a cruel line of tacks glued to its face. Initially, you may see glimmers of humor, play or strange magic. But those soon fade, leaving only the cold glint of alienation. It’s no comfort to read André Breton, the author of the first Surrealist Manifesto, writing that Man Ray treated his human subjects just like his nonhuman ones: “How astonished they would be if I told them they are participants for exactly the same reasons as a quartz gun, a bunch of keys, hoar-frost or fern!”

Though Breton’s writings recur throughout the show, Man Ray never officially joined the surrealists’ ranks. He also dipped in and out of dada, the iconoclastic movement whose founder, Tristan Tzara, lavished the rayographs with praise, providing the title for the exhibition. The catalog cites Man Ray’s “aversion to anything ‘beyond the control of one man,’ meaning himself.” This could just as well explain the artist’s attempt to treat his human subjects as virtually inanimate. What’s beyond the control of one man if not another man?

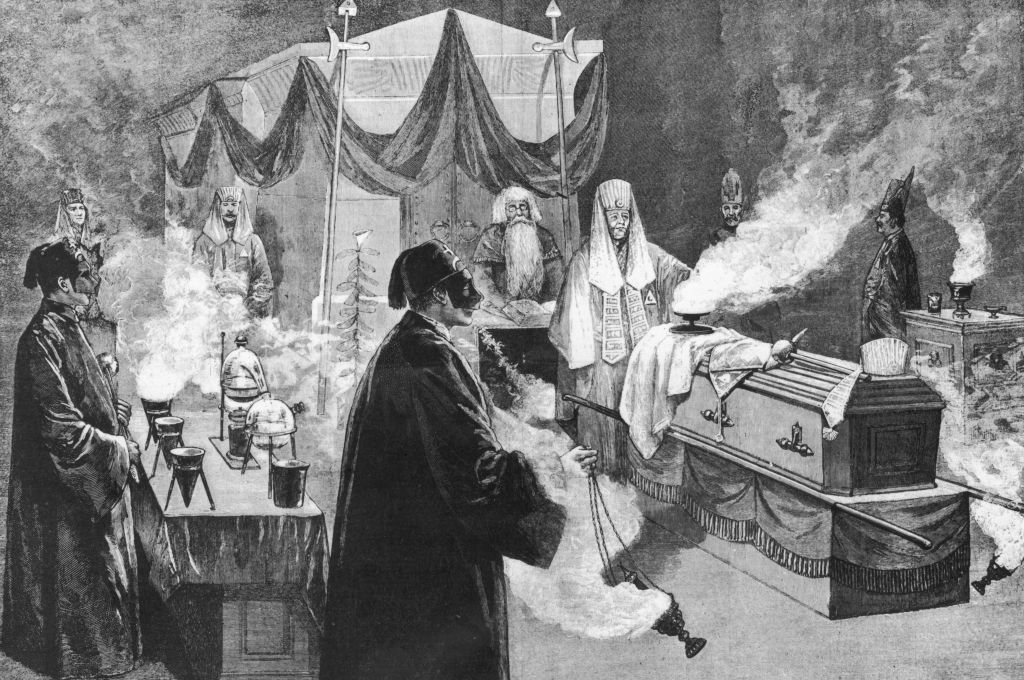

Despite refusing to carry any membership cards, however, Man Ray did photograph the surrealists’ “sleeping fits,” induced trances during which they documented the visions that came to them. He later said of the sessions, in which he declined to participate, “It has never been my object to record my dreams, just the determination to realize them.” The question hangs in the air: what’s the difference? We record our dreams to refer back to them, with the aim to understand the waking world as much as the sleeping one. But to realize a dream is to form the waking world in its mold. If these works are what Man Ray’s dreams look like, that’s not so innocent a wish.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s November 24, 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply