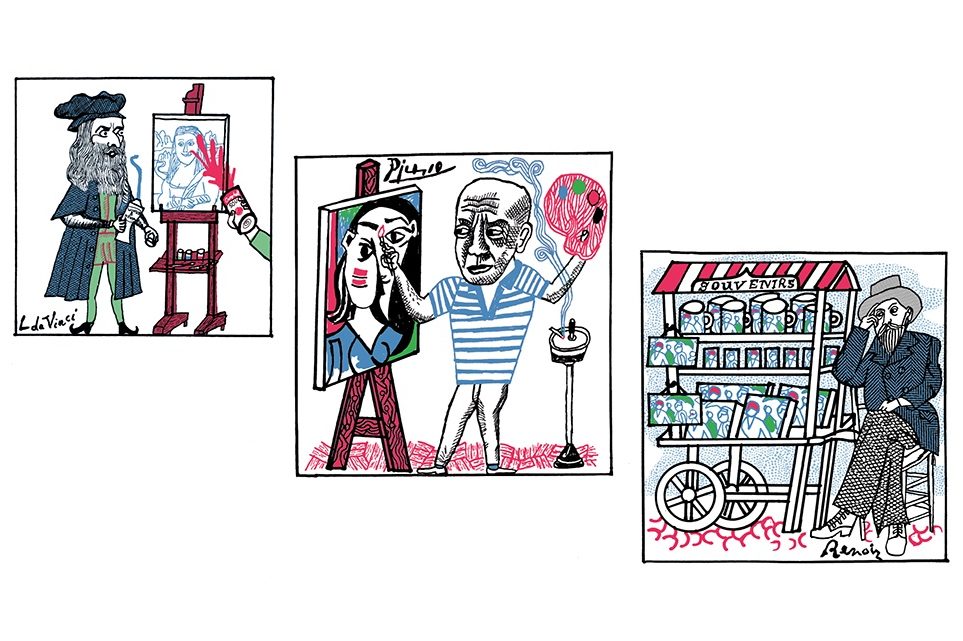

If you won the lottery tomorrow and suddenly had the money to invest in art, what would you prefer: a work from Picasso’s Cubist period (Guitar on a Table, 1919), or an NFT made from AI-based images and shapes? On the one hand, Picasso’s Guitar on a Table isn’t his most famous or even most interesting work — by 1919, the radicalism of Cubism had begun to wane. But on the other, NFTs are a relatively unproven market with dubious artistic merit, and have been linked to art crime, money laundering, and even allegations of human trafficking.

If Picasso couldn’t persuade you to ditch the digital art, what about a painting by Renoir, a sculpture by Rodin, or a triptych of paintings by Francis Bacon? You’d think the choice would be simple enough, but MoMA — the New York gallery founded in 1939 to be “the greatest museum of modern art in the world” — thinks otherwise. It recently announced that it will be reaping the profits of the sale of much of William Payley’s art collection, which it has held since the philanthropist and CBS founder’s death in 1990.

The works are to be sold through the auction house Sotheby’s, and the proceeds — which are expected to top $70 million — will be used to “increase [the museum’s] capacity off-site and online,” according to director Glenn Lowry. Lowry talks of virtual exhibitions, social media, and a foray into the world of NFTs and digital art.

The decision has sparked mixed reactions: the Times ran an editorial which claimed that “museums are right to sell exhibits to expand their digital content,” while NFT creators on Twitter started joking about selling their work to the museum (although, because Twitter is Twitter, some discourse has already begun about how artists should be “embarrassed” if they are bought by the “elite”).

Yet away from the creators of digital art, I’d hazard a guess that many might feel a bit queasy over this decision. The debate over whether NFTs are art is still raging, but it does not necessarily apply to MoMA’s decision. They are selling real art not solely to buy digital creations, but to fund other digital plans — virtual tours, art courses, and videos. Real, tangible art is not being sold for a pixilated version; it is being sold to fund digital museum architecture. This isn’t much different from selling off art to fund a new block of restrooms or a shiny new gift shop.

MoMA would, of course, disagree — they cite the fact that visitor numbers have been down since the pandemic, and things like virtual exhibitions and curator walkthroughs widen access to exhibitions and permanent collections. This is true, but there’s a problem: in selling real art to fund and prioritize its digital reproductions, MoMA’s new plan suggests that a digital encounter with art can replace the real thing. Who needs to visit an exhibition when someone can walk you through it when you’re sitting on your sofa thousands of miles away?

The truth is that virtual exhibitions will never compare to seeing art in person. However close you get to your computer screen, you’ll never be able to feel the weight and heft of Picasso’s impasto paintwork, nor the delicacy of Rodin’s sculpted forms. This isn’t just some airy-fairy art critic nonsense; it’s the truth of art: works are made to be experienced, not simply “learned from” on a website.

Take Joan Miró’s 1960s triptych Blue. I saw it last week in the Pompidou Gallery in Paris, having only ever read about it and seen pictures online before. I, in my ignorance, had thought I didn’t like this period of Miró’s work, but when I sat with the huge canvases on three sides of me, I couldn’t help but be overawed by their power, narrative, and drama. How did the lines break, connect, and alter between the canvases? What happened to the black dots, the tone of the blue? The red? I couldn’t stop looking — something I never would have done flicking between the images on my laptop, or even turning over the pages of an exhibition catalogue.

This is not to say that there is something necessarily ineffable or spiritual about seeing art in person; I am always somewhat skeptical of arguments that put art — and artists — on an unreachable pedestal. But there is something wonderful, and wonderfully tangible, real, and normal, about experiencing art in person.

I am not a complete luddite: I do not agree with those who believe galleries should never sell off parts of their collections. MoMA has said that none of the works which are to be sold were on show in the collection; this is understandable given the scale of the museum’s collection, but it’s a tragedy. They are surely far better off being exhibited at Sotheby’s and then dotted around the world where others might get to appreciate them. (As a side note, I have a huge bugbear with museums not altering their permanent collections enough: the Pompidou Gallery holds a wealth of works by Agnes Martin that they seem not to have exhibited since the late 1990s. I would have no problem if these were sold — for whatever purpose — to other galleries or private collectors which might let them make it out into the world.)

Nor are MoMA’s claims about widening access to be sniffed at. It is impossible to deny that it is far easier and cheaper to watch a video on Instagram than it is to travel to New York and pay the eye-watering $25 to access the gallery. But as a Brit — where almost all of our galleries are free — I can’t help but think there is a better way of improving access to the art. Why not sell off the collection to fund free tickets? As soon as they do that, I’ll be on the first plane over to see the art that is left.