Whatever your favorite theory of creativity, Paul McCartney has a cheery thumbs-up to offer. You think the secret is putting in the hours? “We played nearly 300 times in Hamburg between 1960 and 1962.” Or could it be a wide range of cultural inputs to assimilate and remix? The Arty Beatle hoovered up Shakespeare, Dryden, not just Desmond but Thomas Dekker, Berio and Cage and rock ’n’ roll and light jazz, and sublimated them all. In one of the great missed opportunities, when it came to arranging “Yesterday,” his first thought was Delia Derbyshire. Some people credit childhood trauma: McCartney recalls how his father Jim would weep alone in a neighboring room after Paul’s mother died. The sexual drive? Paul and John wrote “dit-dit-dit” into the chorus of ‘Girl’ purely so they could secretly sing “tit-tit-tit” instead. Drugs? There is a lot of LSD and marijuana here — although “Fixing a Hole” turns out to be about DIY. Or could it be as simple as synesthesia? “I used to see the days of the week in colors.”

The Lyrics, presented in two huge volumes in a slipcase, is at once engrossing and frustrating. It is the closest McCartney is likely to come to an autobiography: 154 song lyrics, ranging from a scrap from a fourteen-year-old hand in 1956 to songs from McCartney III at the end of last year. His comments on each song and the circumstances of its composition are drawn from edited interviews with Paul Muldoon that point towards his muses (his parents; Lennon; Linda).

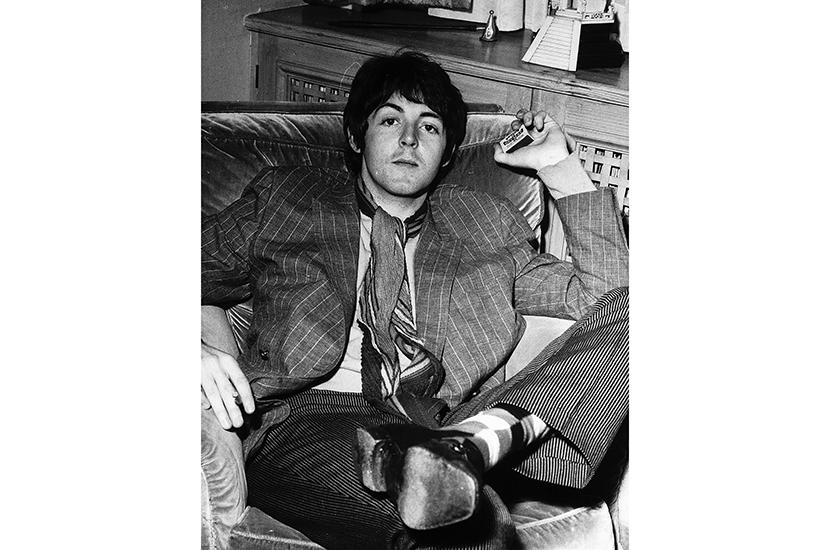

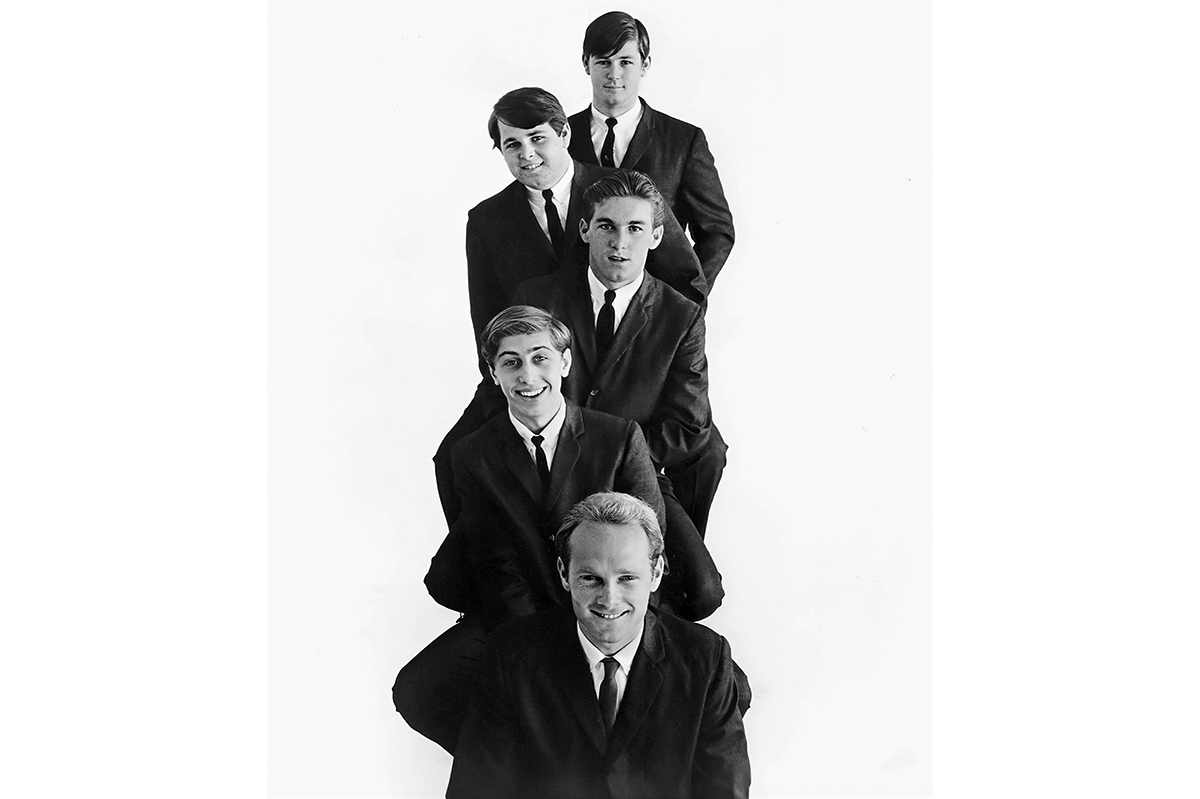

Most are illustrated with photographs and some with the original handwritten lyrics, on scraps of exercise book or hotel stationery. There is little vanity about the selection: “Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da,” “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer” and “We All Stand Together” make it in, though not “Wonderful Christmastime.” The words reproduced are “the definitive lyrics,” so now we can be sure that “Live And Let Die” is set “in this ever-changing world in which we’re living” and not, as many have suspected, “in this every-changing world in which we live in.” At its best, reading it is like watching genius — which McCartney undoubtedly was and fitfully remains — in the process of creation, summoning something out of nothing.

At its worst, the book is infuriating. A lot of the stories are so well-trodden that even hearing them from the author’s mouth adds little value. If you haven’t already heard about him demoing “Hey Jude,” singing “the movement you need is on your shoulder” with an apologetic shrug and being fiercely told by John Lennon that he should keep it, you’re probably not reading this book. Worse, a lot of the anecdotes come round several times. Twice — apropos of “Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band” and of “Honey Pie” — we see the Beatles sliding around in the back of a meat wagon as they are driven away from the concert at Candlestick Park and vowing never again to perform live. Several times during a quarrel Lennon peers over his glasses and says, disarmingly: “It’s me, John.” In “And I Love Her” and again in “I Want to Hold Your Hand,” McCartney moves into the attic at Jane Asher’s family house. In part this is because the songs are presented not in chronological but in alphabetical order, from the moptop “All My Loving” to the psychedelic music hall of “Your Mother Should Know,” four short but epic years later. This has the benefit of avoiding a collapse in quality in the second volume but it unmoors the narrative in time.

If the origin myths of the Beatles songs are overfamiliar, many of the later lyrics here and their stories deserve to be better known. The lovely “Jenny Wren,” recorded in 2004, is a slight return to “Blackbird” but this time with an aching duduk solo. Meditating on it in the book, McCartney is quietly proud of the way the references slide from Our Mutual Friend to the soprano Jenny Lind (the “Swedish Nightingale”), to actual Troglodytes aedon.

McCartney has been huffy about Ian MacDonald’s magisterial Revolution in the Head, which takes a minutely detailed musicological dive into the songbook. But if lyrics were all that counted in popular music, its greatest exponents would be Bob Dylan or Leonard Cohen or Joni Mitchell. The glory of the Beatles in particular was that they married words with melodies — and McCartney is a supreme melodist — and then set them down as great recordings. Some of the lyrics that have the most cleverness as poetry — “Eleanor Rigby,” or “For No One” — in their recorded forms border on the chilly. Conversely, on the page, “I Want to Hold Your Hand” is flat, its vocabulary pedestrian, its ABABBB rhymes trite. In Abbey Road studios, though, it is dense with incident — unexpected chords, McCartney’s voice leaping that exuberant octave on “hold your hand,” the beat clattering out in the closing seconds, the distilled promise of life into the world and all our joy.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.