The Lost Daughter is an adaptation of the Elena Ferrante novel about motherhood that says, quite ferociously: it’s complicated. And: mothers aren’t necessarily motherly, and can feel ambivalence. You’d think it was unfilmable, particularly as the central character describes herself as someone even she doesn’t understand but, directed by Maggie Gyllenhaal — it’s her directorial debut — and starring Olivia Colman, this film is entirely gripping. No ambivalence on that count.

It is carried by Colman who is tremendous, and is being tipped as a potential Oscar winner, if that matters. She is certainly now one of the greats. She is up there with Judi Dench and I do not say that lightly. Both could play a bedside table and somehow bring depth, feeling, an internal landscape. I don’t pretend to know how they do it. I am just grateful for the alchemy. Here, Colman plays Leda, a professor of comparative literature who has come to a Greek island for two weeks, semi-working. Even as she arrives at her rented apartment, with suitcases filled almost solely with books, you understand: this woman is interesting. Best keep my eye on her. In fact, you won’t be able to tear your gaze away.

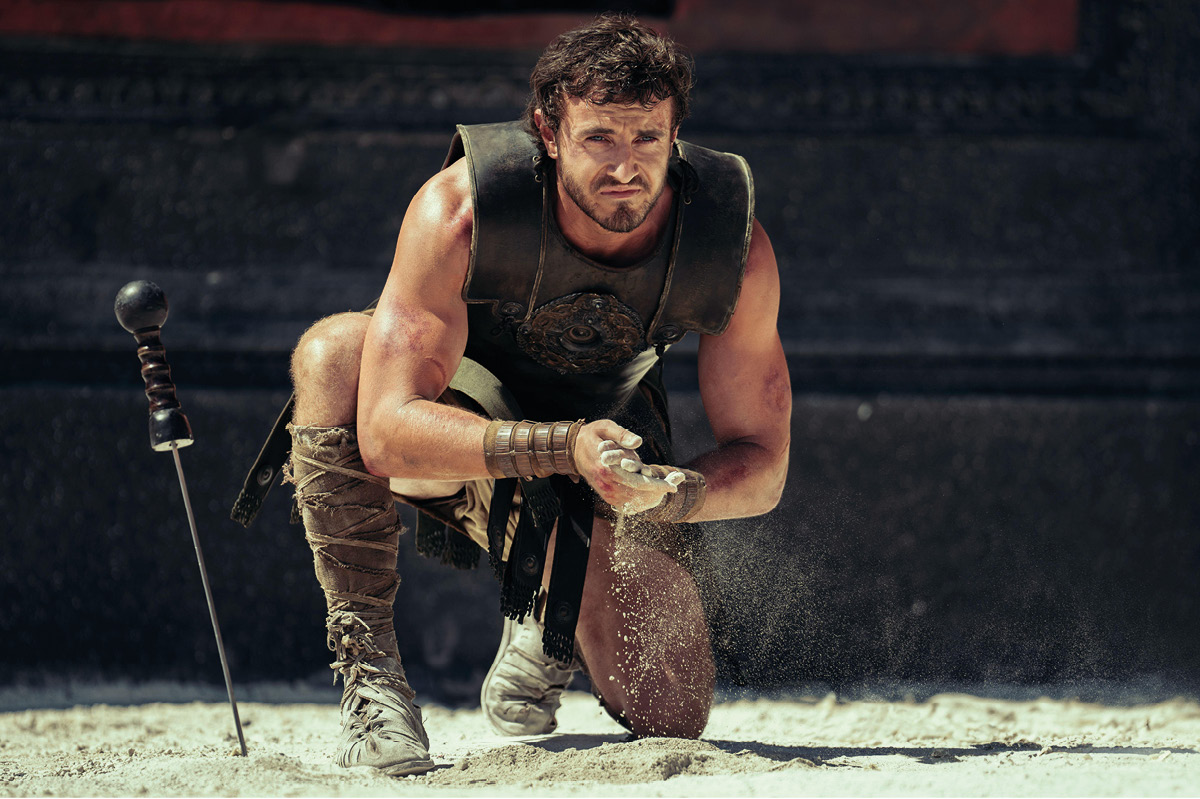

Aside from a local handyman (Ed Harris) and the boy who works the beach bar (Paul Mescal), who pop up every now and again, she is alone. And in her linen beach cover-ups — some choice items from the White Company definitely stole in amid the books — she enjoys the peace and beauty of the secluded sandy beach. (If you haven’t had a vacation in ages, look away. It’s tormenting.) But then her peace is shattered by the arrival of an extended noisy American-Greek-Italian family who, at one point, ask her to move her sun lounger. “No,” she says, although she might have said “yes.” She is never predictable. She is sometimes spiteful, sometimes nice, and can be both in the same moment. She becomes fixated on the young mother within the group, Nina (a dreamy Dakota Johnson, finally freed from the Fifty Shades franchise), and watches her and her little daughter, Elena, intently from afar.

The mood is humid and sultry, as well as passive-aggressive and tense. This family, they’re not good people, she is warned. You know something will happen between Leda and Nina but what? Somehow Gyllenhaal makes this feel like a psychological thriller. There is also the matter of Elena’s lost beloved doll. Leda’s involved in ways she doesn’t understand, as we try to understand for ourselves.

This is slowly, slowly, catchy monkey. One scene may simply show Leda eating an ice-cream or having breakfast on her balcony. But as she continues to observe Nina, she increasingly reflects on once being a young mother herself, when she had to balance having two daughters with building an academic career. This is told via flashbacks starring Jessie Buckley (also first-rate) as the young Leda, and these did sometimes seem long-winded. It could have been more hurry, hurry, here. But the film never loses you, and as Leda’s memories spool back she is forced to consider certain decisions she made. Does she fear Nina is about to make those decisions too?

Adapted by Gyllenhaal herself, this is a literary film with a literary script. One night, in a bar, Leda describes her relationship with her own mother thus: “My mother was very beautiful. I felt like she hadn’t shared it, that in creating me she had separated herself — like pushing away a plate of food she found repulsive.” Yet it always sounds natural, as if we’re all as elusively fascinating in bars. It’s why you cast Colman, I suppose, and can I just say that I knew it when I first spotted her in the British sitcom Peep Show. (I didn’t. But it pleases me to think I did.)

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.