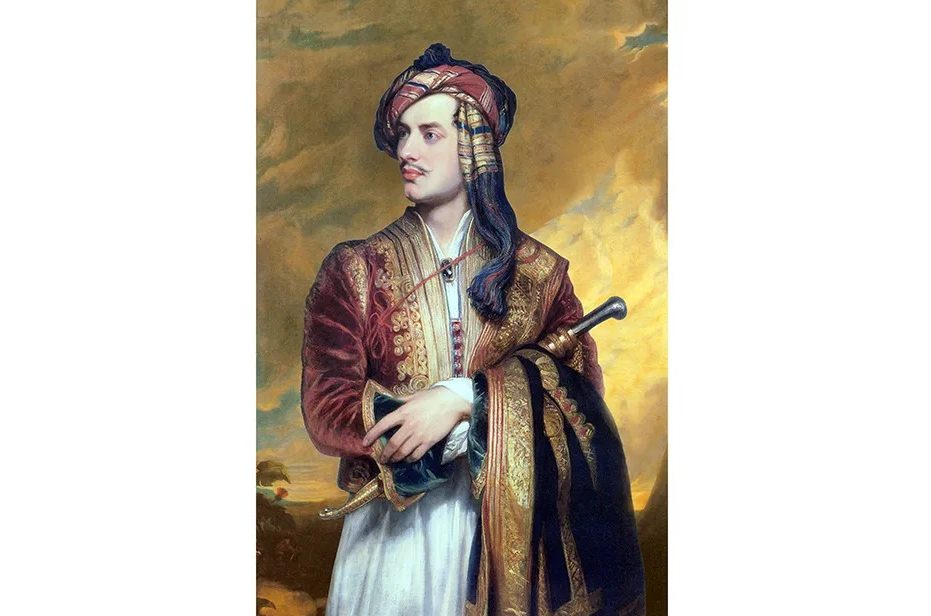

In 1814, at the height of his fame, the poet, libertine and freedom fighter Lord Byron had his head examined. Not by a proto-psychiatrist but by the German phrenologist and physician Johann Spurzheim, who, after making a detailed study of the no doubt amused Byron’s cranium, pronounced the brain to be “very antithetical” and said that it was an organ in which “good and evil are at perpetual war.”

Two centuries after Byron’s death, this dichotomy is as pronounced as ever when it comes to analyses of the poet. His defenders point to his wit, his poetic genius, his heroic efforts in defense of Greek liberty and his personal flair; not for nothing has the word “Byronic” entered the vocabulary as a largely admiring adjective. His detractors, meanwhile, suggest that he was an abuser of women, a pederast and a profoundly overrated poet, whose once lauded work now feels overblown and hollow, with the exception of Don Juan and a few of the lyrics. For good measure, the anti-Byron camp usually remark that he didn’t even succeed in redeeming himself through military glory, dying of a fever in Missolonghi at the age of thirty-six before he could see action.

Writing from Cambridge in 1807, Byron alludes to keeping a tame

bear in Trinity College

Nonetheless, he remains catnip for biographers (and, full disclosure, I am among their number). His contradictions and eccentricities make him a consistently fascinating subject, and even if attitudes towards his sexual escapades and poetry have shifted from indulgence towards more rigorous criticism, there is always a new angle to be taken towards the man nicknamed “The Manager” by his wife Annabella and half-sister Augusta, with whom he conducted a scandalous ménage à trois that resulted in his banishment from Britain in 1816.

Andrew Stauffer has approached what would otherwise be a fairly standard life of Byron through an unusual (if increasingly modish) prism. He takes ten letters that the poet wrote over the course of his life, from an early epistle from Cambridge in 1807 (in which, notoriously, he alluded to his keeping a tame bear in Trinity College) to a late missive written two months before his death in April 1824, in which he talks of a “strong and sudden convulsive attack” that heralded the final decline in his health. Over the course of ten chapters, Stauffer extrapolates the information provided in each letter, providing context and further detail and allowing Byron to narrate his own life story posthumously.

It’s a neat trick, but it doesn’t entirely work. Stauffer is an academic as well as a biographer, and the book feels like a cerebral exercise, an unseen examination paper sprung on bright students who are required to mine every nugget of biographical and literary detail from a sample letter. Byron was a peerless correspondent, perhaps the greatest master of the well-honed missive in the language. Even today, his writings have a rakish swagger that makes them irresistibly compelling, and it is hard not to wish that Stauffer had directed his energies towards a one-volume selection of the best, lightly dusted with relevant commentary, than this retread of one of the most documented literary lives in history.

Not that the book is without interest. Stauffer may not rival Fiona MacCarthy’s definitive 2002 biography for comprehensiveness or insight, but he nevertheless marshals his information in an engaging and readable fashion, although I could have done without some of his colloquialisms. I winced at the description of how “Augusta herself was not good at drawing boundaries” or how she and Annabella “became confidantes and frenemies.” Still, there are laughs both intentional and otherwise to be had. I giggled childishly when I read of how, when Byron and his friend John Cam Hobhouse were received by the potentate Ali Pasha in Albania, Ali “took note admiringly of Byron’s ‘magnificent sabre;’” and, when Byron is at his most swashbucklingly licentious, there is a touch of Flashman to his escapades, as in an 1810 letter to his former housemaster Henry Drury when he unblushingly writes:

At Malta I fell in love with a married woman and challenged an aid du camp[sic] of General Oakes… but he explained and apologised, and the lady embarked for Cadiz, & so I escaped murder and adultery.

Stauffer suggests, drolly: “You could make a case for this being the happiest period, and one of the happiest days, of Byron’s entire life.”

The poet may have been “mad, bad and dangerous to know,” as Lady Caroline Lamb labelled him, but he was also magnificent company — unless you were one of the countless women (or men or boys) he seduced, then ignored or betrayed. We may find him morally reprehensible, but like all great villains, he remains shamelessly captivating. Even a middling biography such as this offers rich pleasure in its recounting of the exploits of someone who stood proudly contra mundum, and became immortal in the process.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.

Leave a Reply