It was November 1843, two years after Prince Albert first introduced Britain to the tradition of the Christmas tree. Charles Dickens was thirty-one, and yet to grow his beard. A dire report on child labor the previous year had worked him up into a compassionate rage. Just as pressingly, Dickens needed cash. The author was already famous for The Pickwick Papers and Oliver Twist, but the public was struggling with Martin Chuzzlewit and, to top it off, his wife Catherine was pregnant again.

Dickens wrote A Christmas Carol in six weeks, amid explosions of laughter and tears at his desk. He knew straight away it was his best work yet, and commissioned a fancy edition to celebrate, complete with gold-edged paper and hand-colored pictures. It was published on December 19 and had sold out by Christmas Eve, but the book was very expensive to manufacture, and profits were meager. It was also immediately pirated, although when Dickens sued for damages, the pirates went bankrupt, leaving him to foot the legal bills. So in the first year, A Christmas Carol lost money, and Dickens moved his family to Italy to manage their expenses.

A Christmas Carol remains a flight of utterly bewildering, huge-hearted genius

In all, though, it was an overnight triumph. Half of London wrote to thank Dickens for what felt like a personal Christmas gift. Within two months, eight separate theatrical adaptations had been staged. The historian Thomas Carlyle took a break from working on his “Great Man” theory to throw two banquets in the spirit of the story. Ever since, the Carol has sold like mince pies, prompting the strongest and strangest reactions in its readers. In 1867, one American industrialist felt himself completely transformed, and sent 200 turkeys to his employees. By the 1880s, Vincent van Gogh was re-reading it every Christmas: perhaps it helped to save his other ear.

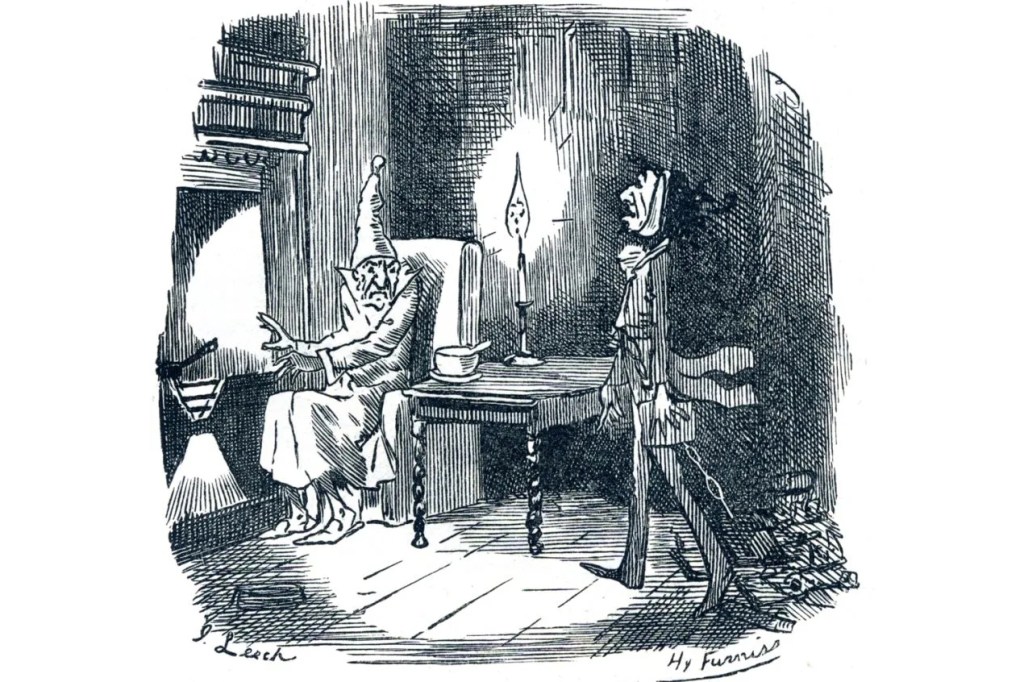

In A Christmas Carol, we encounter Ebenezer Scrooge on Christmas Eve, Bah Humbugging his nephew for falling in love: “the only thing in the world more ridiculous than a merry Christmas.” But he is scheduled for redemption through a series of ghostly visions. In Christmas Past, we see Scrooge’s genesis as a friendless teenager, fearful of a hard-hearted father. In Christmas Present, we meet the impoverished family of Bob Cratchit — the clerk whom Scrooge perpetually refrigerates in his freezing cold office — enjoying their budget goose. We fear for the prospects of Tiny Tim, the crippled son who fits on Bob’s shoulder. And in Christmas Yet to Come, the fatal blow is dealt. If Scrooge refuses to reform, Tiny Tim will surely die — and when Scrooge dies himself, no one will miss him.

But when Scrooge wakes up, it’s still only Christmas Day. Nothing can stop him blessing the local urchins, delivering a turkey to the Cratchits and raising Bob’s salary the following morning. Amid these festivities, Christ takes a back seat, but resurrection is the theme: of Scrooge, of Tim, and of Christmas itself, which always comes round again. As readers, we learn how rarely we live as if we actually knew we were going to die — and how different we might want to be if we ever saw ourselves from the outside.

New readers find the Carol shorter and funnier than expected, but more importantly deeper. There is the scene from Christmas Past when Scrooge’s fiancée cancels their engagement, and the roots of his greed are explained:

“You fear the world too much,” she answered, gently. “All your other hopes have merged into the hope of being beyond the chance of its sordid reproach.”

Underneath the story of a man who obviously doesn’t try, A Christmas Carol is really about the extraordinary difficultly of being kind: the well of sadness, fear and mistakes that traps us in our worst instincts. It is as magical and charismatic as anything by Dickens, written with the special confidence of a writer who knew not only that he had a good idea, but that he was doing a good deed.

Yet the truest test of a myth is whether it can be retold just as well as the original. Dickens himself started the trend, cutting the text down for the 127 public readings he gave over the ensuing years of his life, every bit as dramatic and hysterical as a one-man pantomime. But even he might have been humbled by the delights of the Muppets Christmas Carol version. Michael Caine would have earned his knighthood for his teary and sensitive Scrooge alone, foiled perfectly by the embattled and deserving Kermit. Just as splendid is Miss Piggy in her terrifying rages, and Gonzo as Dickens himself, explaining the concept of omniscient narration. The film did middlingly in its day, impaired by condescending reviews; but it has aged superbly and continues to improve lost children.

A Christmas Carol was written to point the finger at the Scrooge in everyone, but perhaps nowadays most of us feel like Scrooge and Cratchit at the same time. We keep to our own business; the other side is full of humbug; by any objective measure, we are preposterously uncharitable. Yet we can hardly believe how little we get for a year of exhausting work. Somehow, between a nervous future and the miserable past, we have a good Christmas.

Dickens has been criticized for believing that kindness alone could save us, in the place of an agenda for structural change. Nowadays everyone and his uncle has an agenda for structural change — but is no easier to point to a well-meaning person. Meanwhile in some walks of life, outright villainy has returned. No other book leaves you with the same feeling of instant moral resurrection, on top of a massive serving of festive cheer. Almost two centuries since its publication, A Christmas Carol remains a flight of utterly bewildering, huge-hearted genius: the greatest possible Christmas present.

Leave a Reply