The title of this book may offer a clue to its prevailing tone. There’s a certain amount of showbiz gossip involved, but it is essentially a protracted rumination of the “What’s it all about, Alfie?” variety, with plenty of unflinching discourse on matters such as spirituality, depression, addiction and the precariousness of the human condition. “I wondered how many times a heart can break,” the authors write near the end of their tale of untold material privilege and wrenching emotional grief. All too often, is the inescapable answer.

The book is freighted with a certain amount of woe from the start, because its principal author, Elvis Presley’s only child, herself tragically died in January 2023, aged fifty-four, due to weight-loss surgery complications. She left behind three daughters, one of whom, the actress Riley Keough, completed the project from tapes her mother bequeathed her. Lisa Marie’s son Benjamin, known to the family as Big Ben, had predeceased his mother, committing suicide in 2020 at the age of twenty-seven. He bore a striking resemblance to his famous grandfather and, like him, wanted to be a singing star. It’s somehow in keeping with the general tenor of the book to learn that Lisa Marie elected to keep Benjamin’s body on ice in the spare bedroom of her Los Angeles home for two months following his death.

“There’s no law in the state of California that you have to bury someone immediately,” she writes, before adding in characteristically blunt terms: “It would scare the living fucking piss out of anybody else to have their son there like that. But not me. The normal process of death is: the person dies, they have an autopsy, viewing, funeral, buried, boom,” she continues. “It’s all over in a four- or five-day period, maybe a week if you’re lucky. But you don’t really have a chance to process it. I felt so fortunate that there was a way that I could still parent him, delay it a bit longer so that I could become okay with laying him to rest.”

From Here to the Great Unknown is rather that sort of book.

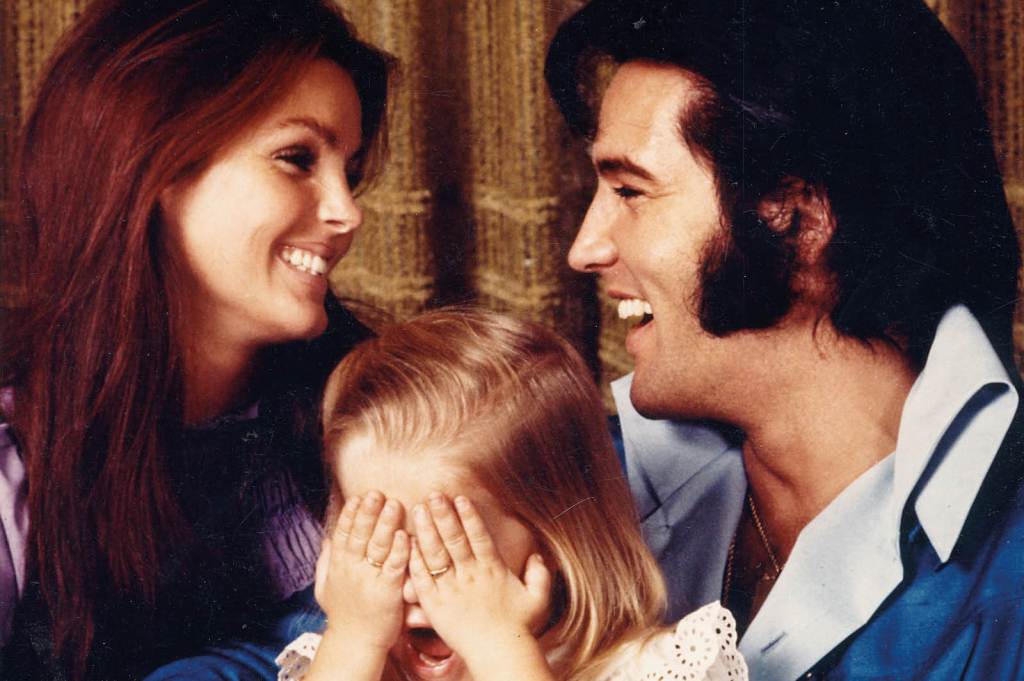

Lisa Marie herself was born to be tabloid fodder, from the first photos of her proud parents Elvis and Priscilla carrying her home amid a gaggle of reporters following her birth in Memphis in February 1968. She seems to have loved and feared her iconic father in roughly equal measure. “He was a god to me, a chosen human being,” she writes, although by the same token, “you didn’t want him to get ~angry with you. If I ever upset him or if he was mad at me at all, it felt like everything was ending. I couldn’t deal with that.” Matters were even more complicated with Priscilla. “She was so upset that she was pregnant with me that she’d only eat apples and eggs and never gained much weight. I was a pain in her ass immediately, and I always felt she didn’t want me.”

“I believe in energy in utero, so maybe I already felt her vibe of trying to get rid of me,” Lisa Marie posits. “She didn’t have great maternal instincts. That might be what’s wrong with me.”

The author spent her early years at Elvis’s mansion Graceland, which she describes as “like its own city, with its own jurisdiction… My dad was the chief of police, and everybody was ranked. There were a few laws and rules, but mostly not.” Activities for the Presley family and its large live-in entourage included discharging an impressive variety of firearms, setting off fireworks, throwing billiard balls at one another in darkened rooms, drinking, taking drugs and eating copious quantities of fried food. Elvis himself was a night owl, and not at his best before about four in the afternoon. Sometimes an aide had to lift him off his bed and pump his arms up and down to jump-start him.

In this distorted funhouse of a home, Lisa Marie slept in a giant, hamburger-shaped bed and roamed about the place in a customized Harley-Davidson golf cart her father bought her. The staff rarely told the little girl what to do, and she had the retaliatory equivalent of a nuclear bomb at her disposal when they did. “One day I was tearing up the backyard with the cart and someone told me to stop doing it, and I said, ‘I’ll tell my father on you when he wakes up’… I was wild,” we learn.

Lisa Marie’s life changed for the worse in 1973, when her parents divorced and she moved with her mother to Los Angeles. She missed the looking-glass world of Graceland, and her snooty school in Beverly Hills was a “fucking drag,” although set against this there was the moment when Elvis himself appeared for a parent-teacher conference. In a departure from the standard protocol on these occasions, “he was wearing black pants and some kind of blouse, as well as a big, majestic belt with buckles and jewels and chains, along with sunglasses, and he was smoking a cigar.”

From time to time, father and daughter would fly back to Memphis together, “and he would land the fucking plane, too,” Lisa Marie notes. “At the end of the trip he would get in the copilot seat, which made everybody nervous, and announce, ‘Ladies and gentlemen, please fasten your seatbelts, Elvis is going to land the plane.’” The nine-year-old was visiting Graceland in August 1977 when her father succumbed to a fatal heart attack, precipitated by an extensive drug habit, an event she recalls movingly here.”

Somehow it is no great surprise to learn that Lisa Marie’s adolescence and early adulthood were a merry-go-round of opioids and sex, from which she periodically alighted only for her latest stay at a rehab facility. In 1994, she went to the Dominican Republic to obtain a quickie divorce from her first husband, the father of this book’s co-author, and as an alternative married Michael Jackson. “I fell in love with him because he was normal, just fucking normal,” she writes, although this judgment may only be true from the perspective of one who had spent her early years at Graceland. Before long, however, “Michael started going to the doctor’s office a lot. I’d pick him up and he would be really out of it… One of his family told me that it was a pill thing.”

When accusations emerged of child abuse at Jackson’s estate Neverland, Lisa Marie loyally stood by him. Even so, she admits, after that “things started to go downhill,” largely because of her husband’s burgeoning drug habit. They divorced in 1996. In 2002, she married the actor Nicolas Cage, a union that lasted for 108 days. At some point, Lisa Marie’s $65,000 diamond engagement ring went flying over the side of a boat while the couple were sailing off the coast of California. Professional scuba-divers were summoned but failed to retrieve it. Lisa Marie later said that the Elvis-obsessed Cage had considered her just another souvenir.

A fourth marriage ensued, to a hirsute young guitarist, but it, too, was to add to an affinity for divorce hearings that practically amounted to a collector’s mania. At some stage, Lisa Marie forsook the spangled palisades of Beverly Hills for the more bucolic charms of a village in the southern English countryside, apparently chosen for its proximity to the headquarters of the Scientology Church, a religion she first patronized but later renounced.

Her involvement with Scientology began in unusual fashion. Lisa Marie writes of her fourteen-year-old self, “My mom made me live with her, but I was miserable. It was clear she didn’t want me there. She tried to make me go to a boarding school, but it never worked out, so in the middle of the night she made me pack my bags and she took me to the Scientology Celebrity Center and dropped me off.”

Amid the subsequent litany of drink, drugs and ill-advised relationships, Lisa Marie somehow found time to release three well-received pop albums, as well as several duets with her late father patched together using archival recordings. Like Elvis, she was also notably generous to charities, despite filing papers in one of her divorce hearings in which she claimed to be $16 million in debt.

It’s not often that you feel the tectonic plates of received pop-culture wisdom moving beneath your feet, but something like a seismic shift in any feelings of envy you may have toward the entertainment industry’s rich and famous may well take place after reading this book, which by rights should come equipped with a public health warning. It’s a story built on grief, and at the heart of it are its late author’s fractured relationships with her parents. There was the sun-god father she adored and feared, and whose body she watched being carried out of his bedroom the day he died: “I saw his head, I saw his body, I saw his pajamas, and I saw his socks at the bottom of the gurney,” she writes. And there was the neglectful, flighty mother. As Lisa Marie concludes in a striking moment of self-analysis: “People think I’m a bitch, because unfortunately I have my mom’s chilly thing.”

Between them the authors have produced a book that’s unsparingly blunt, breathless, when not given over to its numerous philosophical longueurs, and spiced with sexual and chemical shenanigans. The inescapable conclusion is that, for all Lisa Marie’s relentless globetrotting in search of a stable home, her most fixed abode was that mournful hotel her father sang of down at the end of Lonely Street. It’s a tale about the sometimes intoxicating highs of the entertainment business, and a grim reminder, too, of its abysmal lows.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s January 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply