This is the story of the ‘other’ Harvey Milk. We all know about Harvey the San Francisco politician who was tragically assassinated less than a year after he became one of the first openly gay candidates elected to public office in the US. But now, thanks to Lillian Faderman, we also know about Harvey the secular Jew, who renounced his faith but remained influenced and inspired by liberal Jewish values. The grandson of Lithuanian immigrants to the US, Harvey was, for many years, more out as a Jew than as a gay man.

We also discover the restless, wandering Harvey, who moved from state to state, man to man and job to job. He went from college jock to navy deep-sea diver, high school maths teacher, Wall Street securities analyst, bit-part actor, Broadway theatre assistant and camera store owner. It took him two decades to settle finally in San Francisco and find his calling in LGBT+ rights and political candidacy.

En route, he inexplicably briefly dallied with the Republican party, backing the right-wing Barry Goldwater in the 1964 presidential election, before soon afterwards campaigning against the Vietnam war, living a hippie lifestyle and becoming a fully-fledged west coast liberal.

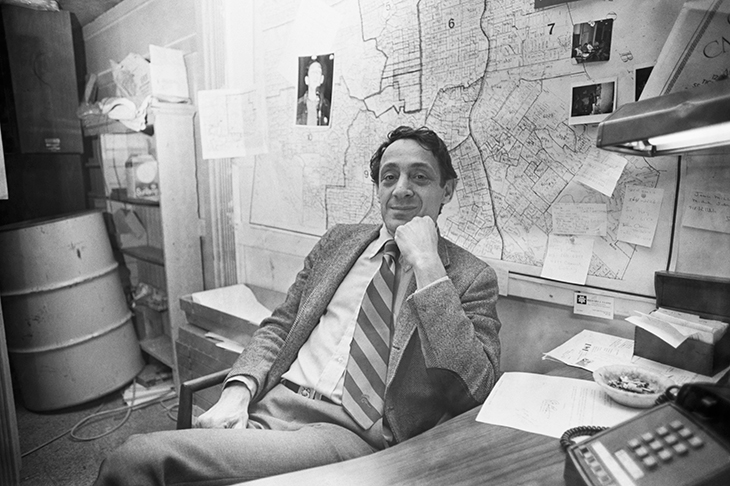

Harvey’s first bid for election was in 1973 to the San Francisco city government, the Board of Supervisors. Spurned by the gay and Democratic party establishments, he had to find a way to create a constituency of support. As an outsider — gay and Jewish — he hit on the idea of an alliance of the marginalised: including Black, Hispanic, senior, disabled and LGBT+ people, as well as disadvantaged workers and tenants. It was a respectable first effort, with Harvey securing 17,000 votes, but not enough to win a seat.

He was never a leftist radical. He rejected the revolutionary politics of the Gay Liberation Front, opposed big government and supported free enterprise. He did, however, embrace GLF’s rainbow coalition philosophy that progressive politics would be most effectively advanced by LGBT+ people allying with workers, racial minorities, environmentalists and others. If LGBT+ people fought alongside them for their rights, he reasoned that they’d be more likely to endorse LGBT+ equality.

In 1973 he put this strategy to the test when he backed the Teamsters union and persuaded gay bars to boycott Coors beer over the firm’s refusal to hire union members. It worked. Coors caved in. In return, Harvey asked the Teamsters to hire openly gay truck drivers. They did, and Harvey’s reputation as an astute political operator was born.

It was further cemented when, knowingly or not, Harvey echoed the community empowerment and self-reliance ideas of Malcolm X, advocating ‘gay economic power’. LGBT+ people should shop in gay businesses, he urged, and those businesses should, in turn, reciprocate by supporting gay organisations and campaigns. In this way, he hoped to forge an economically and politically powerful LGBT+ electoral bloc.

On his second run for supervisor in 1975, Harvey tripled his vote but lost narrowly, coming seventh in a race with six vacancies. A bid to win a California Assembly seat the following year also failed. And the campaign burn-out caused the break up of his long-time relationship with Scott Smith. It was a double blow for Harvey but, as ever, he bounced back and finally won the race for supervisor in 1977 — partly thanks to significant backing from the macho labour unions. This victory came only five years after his first run.

At his swearing-in ceremony, ever the trail-blazer, Harvey condemned the ban on same-sex marriage. Although only elected to the San Francisco city council, he soon became one of the most famous out gay men in the US and inspired other LGBT+ people to seek public office. He showed it could be done.

Once elected, Harvey championed and succeeded in getting his long-cherished gay rights bill passed. He also pushed for free public transport, recycling schemes, laws against animal cruelty, curbs on high-rise developments and new initiatives for senior citizens.

His subsequent campaigning helped achieve what many people thought was impossible in that homophobic era: the 1978 defeat of the Briggs Amendment that would have banned gay teachers and advocates of LGBT+ rights from California’s schools. Harvey was on a roll. He set his sights on becoming mayor of San Francisco, and perhaps even running for congress.

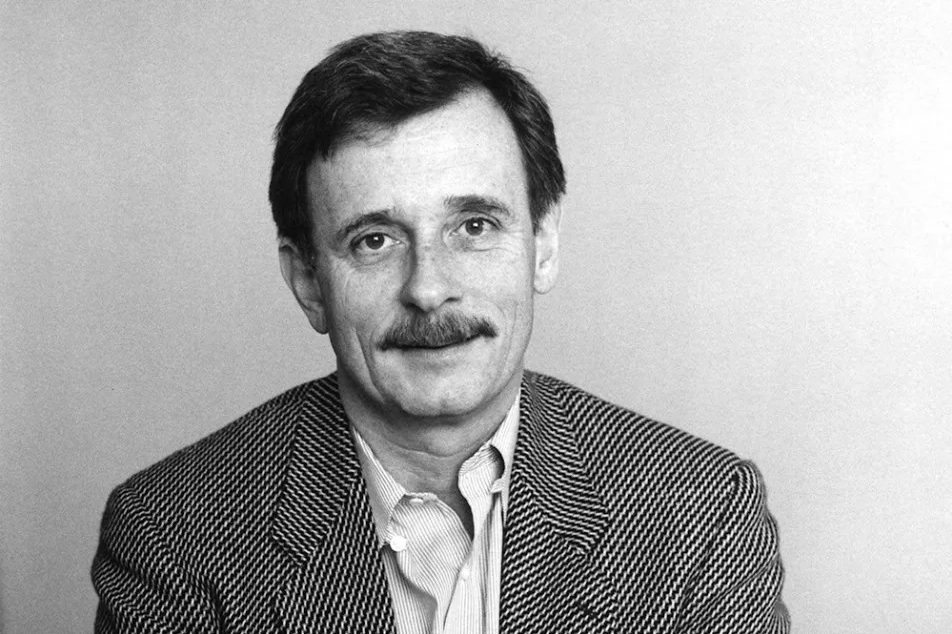

But that was never to be. Twenty days after the stunning win against Briggs, Harvey was shot dead in City Hall by a homophobic fellow supervisor, Dan White. The assassin was acquitted of murder and given less than eight years for manslaughter. His attorney claimed that White had eaten too much junk food on the day of the killing and thus could not be held responsible for his crime.

This article was originally published in The Spectator magazine.