In Whiskerology, Sarah Gold McBride combs through a bristling, tangled mess of data, facts and theories about gender, race, national identity and their relationship to – yep, you guessed – hair. Do not buy this book if you are looking for a fun read about vintage updos, goatees and ponytails; Ye Olde Horrible Haircuts it is not. It’s a book about hair as a kind of cultural text; readable, manipulable, highly permable and ideologically curled. One does not, it turns out, simply go and get a haircut: one enters a vast semiotic salon, more Saussure than Sassoon, where you’re lucky to get out without a scalping.

McBride is a 21st-century American scholar writing about 19th-century American hair, but the manner is classic mid-20th-century French plait. Roland Barthes – remember him? – famously explained how everyday objects are invested with ideological meanings that serve to naturalize particular social orders: detergents symbolize the miraculous power of science to purify stuff; wrestling is a form of moral spectacle. And Michel Foucault – remember him? – traced how bodies become enmeshed in networks of knowledge and power, used to define, discipline and diagnose. Hair, in McBride’s telling, functions in exactly this mysterious, chic French way. A beard is not just a beard but a sign, depending on the beard-wearer, of the ruggedness of the frontier, say, or the honesty of the republic; or is a mark of untrustworthiness and racial otherness. Long, flowing locks may connote moral purity, but also erotic excess. Ideology flows hither and thither through the follicles.

McBride organizes the book around four areas in which hair, according to her, was a “site of debate” in 19th-century America – long hair, facial hair, the scientific study of hair and hair’s role in disguise and deception. Each of these strands, she argues, is knotted with the kinks and tensions of an emerging nation convulsed by civil war, industrialization and new theories of the body, where hair was not only manipulated by its wearers but was also enlisted by the state and by science to stabilize or undermine identity.

Her argument is both utterly straightforward and distinctly weird and wonderful, in that slightly perverse academic fashion which combines statements of the obvious – “for all its malleability, hair is not entirely of the wearer’s choosing, unlike clothing, hats, jewelry and other accessories” – with strange and fascinating examples that support her thesis. Basically, to cut a long story very short, or down to Number 1 all over, the 19th century saw the body increasingly subjected to empirical scrutiny through physiognomy, phrenology and, later, racial anthropology. And just as the shape of a skull or the angle of a jaw was believed to disclose character, so too might a beard, a lock of curls or a suspiciously cropped coif. In a brave new world where citizens were learning how to read one another, people grasped on to hair as a signifier and guide to “authentic meaning.”

Long flowing locks may connote moral purity, but also erotic excess

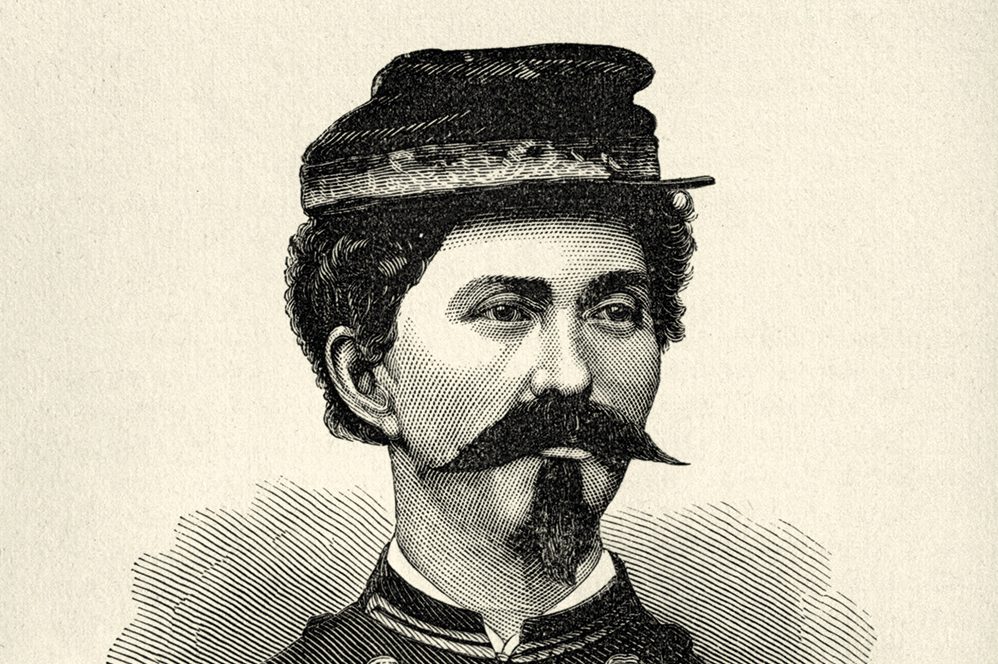

Facial hair provides one of McBride’s most convincing case studies. The “whiskerology” of her title is no mere whimsical coinage, but a serious account of how beards became a locus for negotiating masculinity, morality and political ideology. In early 19th-century discourse, the clean-shaven face represented Enlightenment rationality and moral clarity. By mid-century, however, beards had come to symbolize a more robust, muscular masculinity, tied and tethered to frontier mythologies and patriotic virtue. Yet this meaning was hardly stable. McBride shows how African-American men’s facial hair was subjected to racialized readings, portrayed as either effeminizing or dangerously animalistic. Even bearded women, exhibited in freak shows or circulated in medical literature, unsettled gender norms while also reaffirming them through spectacular exception.

Similarly, the chapter on the scientific analysis of hair draws some interesting links between the nascent fields of trichology and forensic anthropology and the broader project of making the American body legible. In an era when everything from temperament to criminal guilt was thought to reside in bodily signs, hair offered a tempting form of evidence. It was classified, measured and often preserved as relic, sample and proof. As for hair fraud, the story of Loreta Janeta Velazquez disguising herself with a wig and false mustache in order to be able to serve in the Confederate army is just one of McBride’s entertaining examples.

There is, apparently – but of course! – a whole “emergent field of hair studies,” which is where McBride situates her own work and which draws upon “anthropological, historical and black feminist hair scholarship” to provide “useful models for thinking about hair culturally, historically and materially.” Whatever the new models of thinking about hair – and let’s hope for all our sakes it’s not another return to the fringe or mullet – the breadth of McBride’s sources is admirable, ranging from medical treatises and beauty manuals to court records and visual ephemera.

In a country undergoing seismic shifts – economic, political and demographic – hair, it turns out, is a site of both reassurance and anxiety. Hair-studies scholars of the future, examining the evidence of the early 21st century, will doubtless have all sorts of interesting things to say about Donald Trump’s long golden locks, Javier Gerardo Milei’s moptop and Keir Starmer’s overuse of gel. Hair may not tell the truth but it surely remains an indicator of character. For the record, if you can’t tell, I’m bald, while McBride has lovely pre-Raphaelite curls.