“Everywhere I could see India, yet I could not recognize it.” So said India’s great national poet Rabindranath Tagore of South-East Asia, after traveling there in 1927. Tagore was fascinated by how elements of ancient Indian culture had found their way eastwards: gods, temple architecture, the Sanskrit language and the great epics the Ramayana and the Mahabharata. A nationalist but also a universalist, Tagore welcomed the reshaping of these ideas by the people who received them, a process whose fruits he encountered in Malay literature and Balinese dance. He even hoped that one day a “regenerated Asia,” making creative use of its shared cultural heritage, might heal the world of the wounds he believed had been inflicted on it by the modern West.

The Golden Road is William Dalrymple’s attempt to piece together the story of which Tagore found traces on his travels: India’s transformative influence on the world around it between the third century BC and 1200 AD. He writes:

What Greece was first to Rome, then to the rest of the Mediterranean and European world, so at this period India was to South-East and Central Asia and even to China, radiating and diffusing its philosophies, political ideas and architectural forms.

The result was what Dalrymple, borrowing from his fellow historian Simon Sebag Montefiore, calls the “Indosphere:” great swathes of Asia which became host to Indian religion, music, dance, art, astronomy, mathematics and more.

Great swathes of Asia became host to Indian religion, music, dance, art, astronomy and mathematics

The very breadth of this story, Dalrymple suggests, has frustrated its telling until now. It has ended up divided across different academic specialisms while falling victim to the scholarly fashions of the past half century. Writers have preferred to emphasize the way recipient societies engaged with, and reworked, incoming ideas rather than risk repeating the colonial-era trope of a single sophisticated culture civilizing the savages. In seeking to offer a properly joined up account of Indian influence, Dalrymple offers as his controlling image a “golden road” running westwards from India into Africa, Persia and the Roman Empire and eastwards to South-East Asia and China.

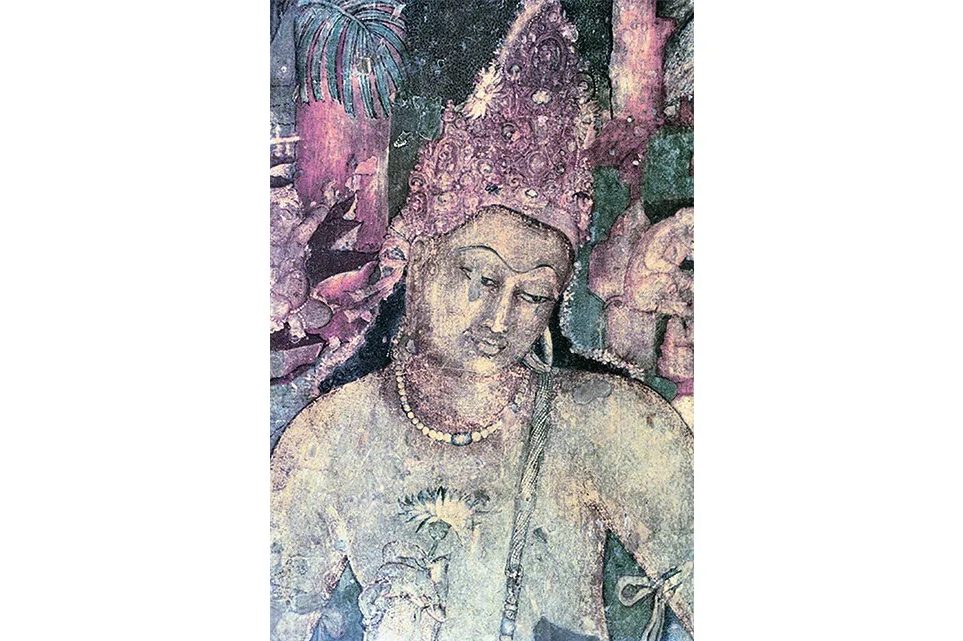

We begin with the tale of a British hunting party in 1819 making its way through thick jungle in India’s Western Ghats and stumbling across the Ajanta caves: thirty rock-cut Buddhist temples and monasteries dating back to the second and first centuries BC. Apparently not the most cultured of men, the leader of the party, Captain John Smith, took out a knife and carved his name, regiment and the date into a pillar just above an image of a Buddhist deity. Later generations would treat with rather more reverence the art that adorned the walls of the caves: a series of murals depicting scenes from Buddhist stories — hunts, battles and glorious evocations of courtly life. The Ajanta caves are now a Unesco World Heritage site.

Marveling at the murals’ vivid realism and their inestimable value as a record of ancient life (as always, his enthusiasm is infectious), Dalrymple uses the Ajanta caves to introduce us to the early history of Buddhism, the religion being the first Indian export to travel the golden road. We also encounter at this point one of the main themes of his account: ancient India as a place of great dynamism and diversity. The paintings feature

an international cast of characters: Persians, Parthians, Scythians, Ethiopians, Egyptians and even Greeks and Romans, each with distinct clothes, tunics, hairstyles, skin colors and drinking goblets.

With an eye perhaps to contemporary India’s sometimes chauvinistic politics, Dalrymple wants us to appreciate that in this era “India was not some self-contained island of Indianness, but already a cosmopolitan and surprisingly urban society.”

There follows the remarkable story of Buddhism’s spread beyond India’s borders into Central Asia and China, thanks to traders, monks, armies, sponsorship by the likes of Ashoka the Great and Empress Wu Zetian of China, and the hallowed center of learning that was the Nalanda mahavihara in north-eastern India. It is a brisk and lively telling, brimming with memorable characters and skilled evocations of Buddhist art — one of the best ways of tracing the journey of Buddhist ideas around Asia. Buddhism, we learn, became the means by which Indian ideas in all areas of life made their way into China, from medicine and music to astronomy and visions of the afterlife. It was, Dalrymple tells us, “China’s first really intimate encounter with an equal civilization.”

Later in the book, Dalrymple guides us through the adoption of Hindu deities in South-East Asia, the use of Indian architectural styles in the extraordinary temple complex at Angkor Wat and the movement of Indian science and mathematics into the Islamic world and from there to Europe. Almost all of this occurred via unforced cultural conquest rather than the raw projection of power. India was, after all, a shifting patchwork of kingdoms for most of this long period rather than a single polity interested in, or capable of, pushing its Asian neighbors around. A notable exception was south India’s Chola Empire of the tenth and eleventh centuries, which extended into Sri Lanka and parts of South-East Asia. But even here, alliances and trade — especially with the Khmer — were what counted most in the outward spread of Indian ideas.

The Golden Road is at its best when the facts of export are set alongside the rationale of the importers: the attraction for Khmer rulers of Hindu concepts of divinely ordained kingship; the efficacy of an Ayurvedic powder in curing a Caliph’s indigestion; the elegant simplicity of Indian mathematics, thanks to Brahmagupta’s innovations in using zero and negative numbers. In places, the point of view of societies importing Indian ideas feels a little under-explored. We discover that India’s crafts and technical expertise were adopted far earlier than its gods in Myanmar and Thailand, and it would be interesting to know why. Also, why was it that in India, Hinduism and Buddhism would be bitter rivals while the two traditions managed mostly to co-exist in South-East Asia? Korea and Japan perhaps deserved more space, too, as enthusiastic adopters of Buddhist teachings, rituals and deities. Some would no doubt argue that since Buddhism made its way to Korea and Japan primarily as part of a package of Chinese ideas, those stories belong to an account of the Sinosphere rather than the Indosphere.

In any case, as Dalrymple tells us near the start of his book: “Over half the world’s population today lives in areas where Indian ideas of religion and culture are, or once were, dominant.” That would be rather a lot of ground to cover in full even for someone of Dalrymple’s powers. What we have here is a richly woven, highly readable account of the highlights of India’s outsized influence on the world. It is also a celebration of cosmopolitanism and cultural exchange, written with passion and verve and hinting at an optimism for India’s future of which Tagore himself would no doubt heartily have approved.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.