North Korea watchers are good book-buyers, rarely able to resist scratching that itch of interest caused by the world’s worst regime. Accounts by escapees sit on our shelves alongside the memoirs of anyone (Kim Jong-il’s sushi chef, for example) who has come into contact with the country or its leadership. Some books, such as Barbara Demick’s 2009 Nothing to Envy, break through to a wider audience. But the questions still need to be satisfied. What is the world’s most closed society like? What do its captive population actually believe? And who are the leaders of this communist monarchy?

Through open source material, repeated travel to the country and first-hand interviews with exiles, Anna Fifield covers what can be known about the Kim family’s third-generation ruler. Those anticipating James Bond villain stories will not be disappointed. We read of the young dictator sitting in his coastal resort playground of Wonsan as his munitions chiefs use their new 300mm guns to turn an offshore island to dust. Elsewhere, he sits smiling at the desk in his beachfront house as his rocket scientists roll out a missile-launcher and blast the munition off in the direction of Japan for his edification. On rare foreign trips, such as last year’s summit in Singapore, he travels with a special portable toilet so that no samples are left behind. And after a recent dinner with the South Korean leadership, his staff swept through the room to collect and forensically clean all glasses and cutlery used by Kim and his sister.

One of the challenges in writing and reading about North Korea is to get the right balance between the hilarity and the horror. For there is a surreal oddity to the place beyond anywhere else on earth. At the same time, it’s the only country today where comparisons with the totalitarianisms of the last century can feel inadequate.

In her unsensational account Fifield (who is Beijing bureau chief for the Washington Post) navigates this course as well as anyone can. Kim Jong-un is not a sympathetic figure, but from his schooling in Switzerland and glimpses of his upbringing it is possible to see him as simply the most privileged captive of that system his grandfather set in motion — one which, at this stage, just wants to survive. He was being dressed up in a military commander’s uniform — and deferred to as such — before the age of ten. But once he succeeded to the portable throne at 27, he did what any new tyrant who needs to prove himself would do: executed his uncle, ordered the chemical weapon assassination of his half-brother at Kuala Lumpur airport and accelerated his country’s nuclear program. His challenge is to lift his country out of its immiseration, without making it so open that the regime falls. The ongoing cost to his people is impossible to quantify.

In North Korea, each neighborhood of 30 or 40 houses has a people’s group and ‘leader’. Nobody can stay in anyone else’s house without notifying the authorities. The leader can inspect any apartment at any moment to ensure that the state radio issued to every house is not turned down or changed to another frequency. Cell phones (on a restricted local network) are checked for unauthorized music, photos or evidence of extramarital relations. People are encouraged to report on neighbors thought to be eating white rice or meat suspiciously often. The system of concentration camps for those suspected of ideological crimes remains in place.

Consumption of various types of gut-rotting alcohol see many people through.As I discovered one night in Pyongyang, the local soju is of an exceptional toxicity, while the various beers make the head jangle slightly before leaving a sandy residue in the mouth. For others, drugs provide solace. Fifield interviews a North Korean drug dealer near the Chinese border who explains:

‘Taking [crystal] meth is part of ordinary life. My customers were just ordinary people: police officers, security agents, party members, teachers, doctors. Ice made a really good gift for birthday parties or for high school graduation presents.’

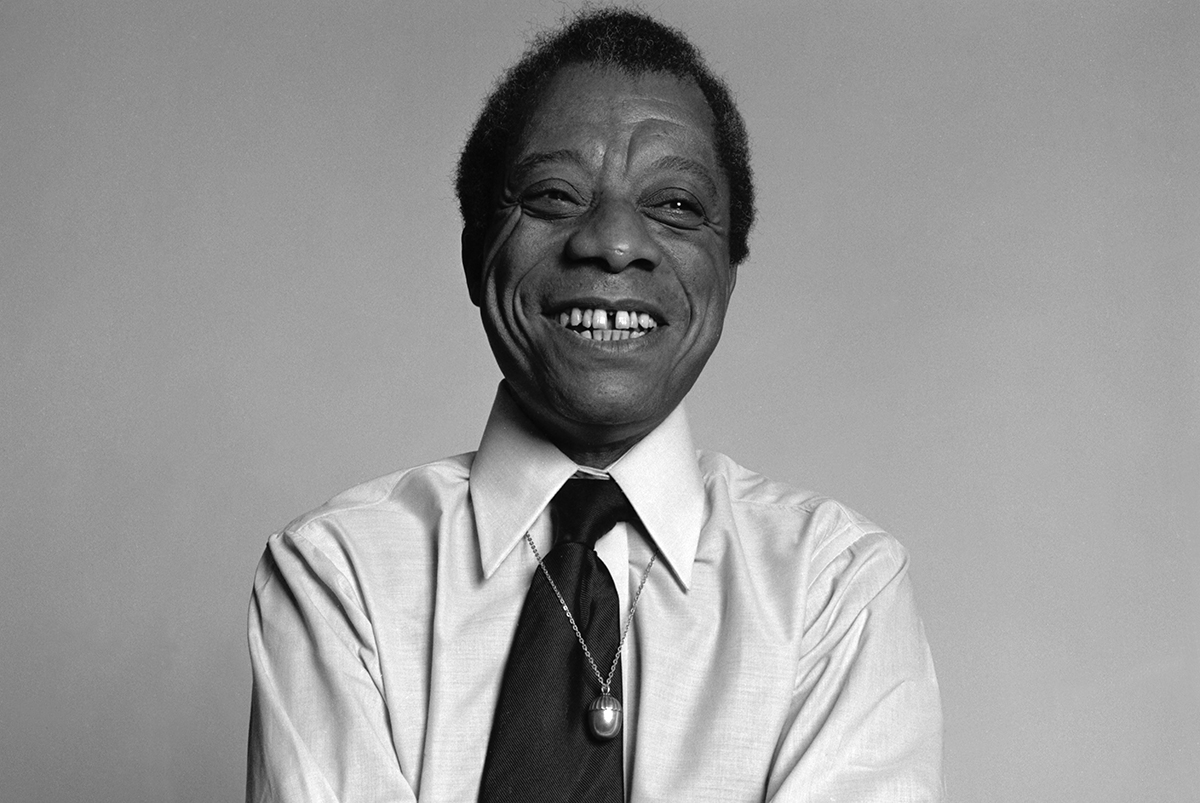

Of course, the elite eke out their enjoyments in their own fascinatingly bizarre style. Intelligence agencies have sometimes tried to get information on the Kims through these enthusiasms. On at least one occasion the CIA attempted to gain details through the medium of Eric Clapton (two of Kim Jong-il’s sons are fans). That effort fell through; but the most successful unofficial diplomatic route to Kim Jong-un in recent years has been through the basketball player Dennis Rodman. At the end of one of their earliest meetings in Pyongyang (a boozy affair even by North Korean elite standards), Rodman delivered a long, rambling toast which reportedly ended: ‘Marshal, your father and your grandfather did some fucked-up shit. But you, you’re trying to make a change, and I love you for that.’ During the karaoke that followed Rodman sang ‘My Way’, while Kim Jong-un attempted James Brown’s ‘Get on up’.

Was Rodman right? During his time in office Kim Jong-un has made some bold diplomatic moves towards Washington and Seoul. But the world still has no precise measure on him. In 2017 the internet was busy giggling about the latest set of photos to come out of North Korea in which Kim was shown peering at a silver metal casing about the size of a large barbecue. How ridiculous. How funny. A day later the North Koreans detonated a device with a yield of 250 kilotons (roughly 17 times the size of the bomb that destroyed Hiroshima). As one western nuclear scientist puts it: ‘People are surprised that a backward country can do this. But in this business, they are not backward.’

The nation’s nuclear progress is Kim Jong-un’s biggest achievement to date. On its own it will guarantee that he remains safe from foreign military intervention. Perhaps he will allow himself — and the North Korean people — some other achievement during whatever years he has left. Or perhaps he will simply remain in place, living the high life on soju and basketball, presiding over the world’s most unnecessary and humanly wasteful basket-case.

This article was originally published in The Spectator‘s UK magazine.