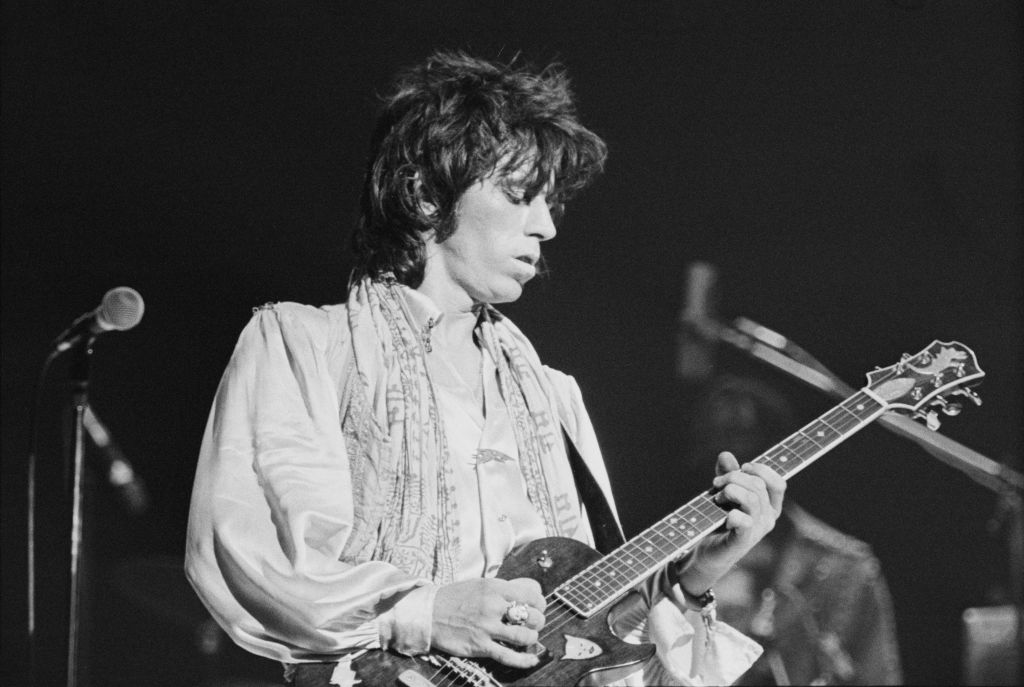

Most of us have at one time played the you-couldn’t-make-it-up game. What were the odds back in, say, 1973, that millions of us would casually engage in Jetsons-style video chats, conduct business at the swipe of a thumb, or consider the prospect of a space-tourism flight courtesy of Virgin Galactic? Or for that matter, rue the fact that the all-conquering Oakland Athletics might fall so low as to become the worst team in baseball last season, with a dismal 50-112 record? Perhaps the biggest shock to someone contemplating the future in 1973 might have been the knowledge that Keith Richards, the guitarist and primary creative force of the Rolling Stones, would still be alive and well at the time of his eightieth birthday on December 18, 2023.

Wrecked. Sick. Zombielike. Undead. Suicidally wasted. A rock and roll Baudelaire. That’s how some of the press described Richards at around the time of the Stones’ great Sticky Fingers and Exile on Main Street albums of the early 1970s. And those were just the more benign of Keith’s critics, who at least admired him for his obvious songwriting ability. In 1973 the editors of Britain’s New Musical Express put Richards at the top of their list of “rock stars most likely to die” within a year. Even by prevailing industry standards, it has to be said that Keith was just a touch out-there, as he later confirmed when coming to describe his daily breakfast routine of the era:

“I’d take a barbiturate to wake up… a Tuinal, pin it, put a needle in it so it would come on quicker. And then take a hot cup of tea, and then consider getting up or not. And then a Mandrax or a Quaalude… And when the effect wears off after about two hours, you’re feeling mellow, you’ve had a bit of breakfast and you’re ready for work.”

When coming to consider the somewhat chaotic results that ensued, the Richards biographer finds himself spoilt for choice. Nor would the word “mellow” necessarily be the one that first springs to mind.

There was, for instance, the moment in 1971, when, for tax-avoidance purposes, Richards found himself living in Nellcôte, a mock-Roman villa perched on a clifftop overlooking Cap Ferrat on the French Riviera. Relations between the haggard-looking rock star and the local community were to be strained throughout the two years of Keith’s tenancy. One afternoon he got into a minor traffic scrape in the nearby town of Beaulieu. The harbormaster, one Jacques Raymond, wandered out of his office to investigate, and Keith promptly addressed him as a “fucking Frog”. From this point on, things began to deteriorate rapidly. Keith rashly pulled out a toy gun belonging to his two-year-old son, and M. Raymond in turn drew his own very real revolver. A fast-thinking minder intervened to calm things down, and Richards later invited the local mayor up to Nellcôte for dinner and a few autographed albums, after which the incident was officially considered closed.

Or there was the time when Richards and Mick Jagger were arrested and charged with drug offenses following a raid on the former’s house in the English countryside. The two Stones were found guilty and given sentences of twelve and three months respectively. Both later won their appeals against conviction, although, for Keith, it was to be only the first in a series of court appearances that amounted to a virtual season ticket until the late 1970s.

In June 1973, the police carried away several boxfuls of drugs and ammunition following another visit to Richards’s house, an offense for which he eventually got off with a fine. Keith celebrated the result that night in a London hotel, unfortunately managing to burn his room down in the process.

On another occasion, Stones publicist Les Perrin and the band’s friend Ian Stewart helped get Richards out of bed, into a car, up the motorway, through security at Heathrow Airport, onto a jet, and, seven hours later, safely down the ramp in New York. He remained asleep throughout.

Or (just a bit more in this vein, I promise) there was the night in 1976 when Keith decided to drive himself back to London following a concert in the English Midlands, which was the last anyone saw of the guitarist until the police found him at three in the morning, wearing sunglasses, his pockets allegedly stuffed full of coke, wandering up the side of Britain’s M1 motorway, while his pink-tinted Bentley Continental hissed away against the side of a lamppost. Charged with possession, he got away with another fine.

Richards’s twilight years reached their nadir in October 1978, when a court in Toronto heard him plead guilty to heroin possession, but again sentenced him only to seek treatment and perform a charity concert for the blind. Keith has sometimes been called the man to whom death gave a pass. The judicial system certainly did. Following Toronto, he has never again been in trouble with the law.

The survivor’s story is one of the predominant narratives of our times. But not many of them can have encompassed quite the variety of assorted court appearances, ER visits, car crashes and near-cremations of Richards’s journey from the austerity of postwar England to the heights of rock aristocracy, with sprawling estates on both sides of the Atlantic, and a private beachfront property in the Caribbean, to show for it. It’s tempting to inquire into the secret of his longevity, if only to know how best to bottle it for future generations.

It may all be a matter of genes — Keith’s mother Doris lived to be ninety-three — or possibly the fact that for much of the past sixty years he’s had access to the best medical and legal back-up money can buy.

Or perhaps the key to Keith’s survival lies further back than that, and has its roots in the values with which he grew up in the materially strapped years of postwar Britain.

Here some discrepancy exists between the raised-by-wolves legend of Richards’s youth and the reality, with its emphasis on duty, rank and sound traditional values. Keith’s paternal grandparents were both well-respected councilors in the London borough of Walthamstow, where his grandmother served as the first female mayor. His father was among the first to hit the Normandy beaches on D-Day, and was badly wounded as a result. Keith grew up in a household where physical exercise and a severely rationed diet coexisted with a fundamental sense of patriotism and service. As a nine-year-old he was an “angelic-looking” chorister (yes, this is the future Human Riff we’re talking about) singing “Zadok the Priest” to the newly crowned Queen, earned his merit badges as a Boy Scout and showed a pronounced streak of English romanticism by later spending his first songwriting money on the thatched cottage deep in the English countryside where he spends his summers today. For all his narcotic indulgence, there was always something about the surprisingly shy, middle-class lad from the suburbs that was in it for the long haul.

As Keith himself put it in his inimitable style: “I can be the cat on stage any time I want. But really I’m a very placid, nice guy — most people will tell you that. It’s really just to placate this other character that I work.” A prince of darkness, then, but a prince nonetheless.

It may be that what we’re really celebrating this week isn’t so much Richards’s checkered past as the spirit of human endurance that’s seen him become a much-loved, wispy-haired grandfather whose pirate’s grin and engagingly slurred laugh are testament to a life well lived.

When the Rolling Stones got started back at the time of the JFK administration, Keith thought the band might last at most eighteen months. Now he can look back on a sixty-plus year career that shows no sign of stopping anytime soon, with both a new Stones album and a US tour coming up in the spring. Along with the great and sometimes thrillingly under-rehearsed concerts, the whole thing has cost him at least six court appearances, a miserable night in jail, frenzied assaults by fans, cracked ribs, blackened eyes, a couple of onstage near-electrocutions, mountainous legal and medical bills and a permanent place on the US Customs watchlist. And it’s been worth it.

Leave a Reply