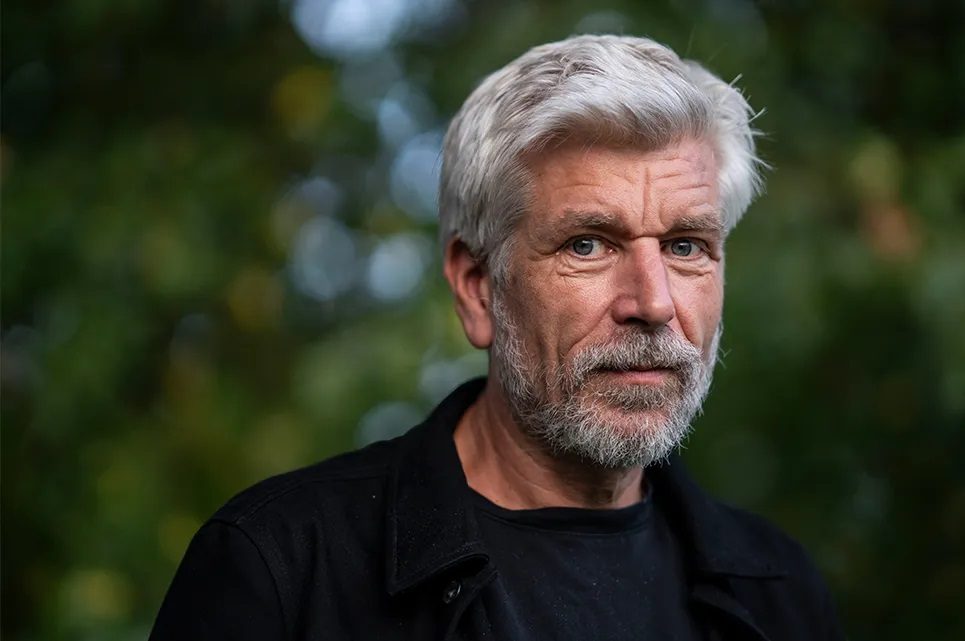

I finished reading the third volume of Karl Ove Knausgaard’s latest series — no longer a trilogy, perhaps a sextet — in three days. The Third Realm is as unsettling, disturbing and riveting as the previous installments, and I was even disappointed that it came in at a mere 500 pages — considerably shorter than the others. But all three books are less dense than those in his celebrated My Struggle series.

There is a lot of dialogue, and Knausgaard’s skill in capturing conversation makes his characters spring vividly from the page. Ordinary failings, such as insecurity, jealousy, duplicity, lust and irritation, are subtly conveyed through a surly comment, a fleeting mutinous thought, a blurted accusation, a smooth lie. As we become privy to the characters’ musings on philosophy, religion, art, neuroscience and love, they grow evermore compelling.

Some are familiar from previous volumes: the funeral director, who discovered a Russian half-sister; the pastor; the bipolar woman. Knausgaard’s understanding of the black lows and psychotic highs of this condition is remarkable; he captures the anhedonia of the former and the manic energy, hallucinations and sexual disinhibitions of the latter with shocking intensity. Other themes of the series also recur — the strange events that coincide with the appearance of a dazzling new star bringing heat and unnatural light; attempts to finally conquer death; the grotesque mutilation and murder of three young men from a satanic band.

This black metal music scene is now explored as a phenomenon — how a fascination with dark elements associated with death could ever have arisen in such a green and socially balanced country as Norway. I shivered when a young woman was drawn to a beautiful youth from this world. We are made aware of how arousing the music can be, filling its followers with adrenaline and providing a thrilling alternative to conventional existence. The parallels to the eruption of punk are obvious. But each generation needs to be more extreme than the last — to a destructive end.

A few might find satanic rituals and strange noises at night hackneyed, but they are used to spine-chilling effect. Others might baulk at scientifically impossible scenarios — but the whole is so gripping, and at any one time, science only understands the tip of the iceberg of observed phenomena. Think of quantum physics.

One flaw I would point out is that parts of this volume seem simply rehashed from previous ones, including the vile fate of a cat and kitten in the bipolar woman’s section (no more animal deaths, please); the dead man sitting up; the pastor burying someone, then seemingly meeting him. Has Knausgaard forgotten he’s used these scenarios — or is he reminding us of them in order to build on them further?

His books are as accessible and creepy as anything by Stephen King and as addictive as your favorite TV drama series. There’s no writer I would rather devour.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.