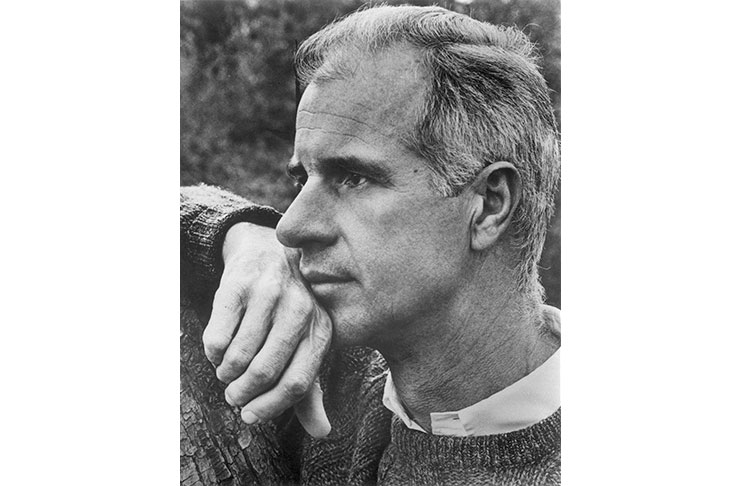

Of how many magazine articles can you recall where you were and what you felt when you read them? If any occur, there’s a reliable chance John Hersey’s ‘Hiroshima’ will figure among them, and not just because it will have been assigned at an impressionable age in school. For the first time in its history, the New Yorker cleared an entire issue in August 1946 to run the 30,000-word piece in full. In Mr Straight Arrow, his chronicle of Hersey’s career, the former Times Literary Supplement editor Jeremy Treglown relates an account of its reception among the international press corps in Rome — every one rapt, occupying their own cone of ‘silence… even in the bar’.

There’s the stark monomial title and intrinsic what-has-man-wrought grip of the subject but, pushing 75 years after the event it describes, ‘Hiroshima’ owes its hold on generations of readers to mastery of tone. Hersey is unflinching, insouciant even, in describing the ravages of the bomb (survivors’ skin ‘sloughing off’); the trauma it inflicts (a mother clinging to the putrid corpse of her infant); and the barbarities it necessitates (the grim triage of a doctor attending to those who could be helped while spurning the mortally injured). But he never privileges such interludes over the quotidian details that otherwise suffuse the piece. The result is a limpid, seamless, quietly devastating delivery that, Treglown writes — quoting Hersey’s writing elsewhere — can ‘burn one’s eyes’.

Treglown’s account of the circumstances of its composition deepen one’s admiration. Consider what Hersey omitted. Postwar Hiroshima had been turned by its erstwhile destroyers into ‘an American base, employing native Japanese staff’ — reportorial gold, but not permitted to intrude on the interlocking stories of six survivors. Yet it begs the question: how did Hersey — not Japanese, not an eyewitness, not a scientist — come to be the first person to communicate the experience to a global audience?

A clue may be gleaned from an often noted quirk to the text: the inclusion among its subjects of a German missionary and a Japanese convert to Christianity — hardly representative. This was a matter of expedience; they connected Hersey to the other characters. But he was also on familiar ground, being himself the son of US missionaries, stationed during his early childhood in China. He traversed the way-stations of privilege — Hotchkiss, Yale, Cambridge — continuing thence to the executive track at TIME, but was at bottom a ‘mishkid’ of shabby genteel stock — a scholarship boy.

Then there was that novelistic execution, held up as a precursor to ‘New Journalism’ (in its use of the devices of fiction at least; Hersey was sniffy about the first-person or otherwise inserting himself into his work). Freed from the tacit self-censorship of war reporting, he yearned to write something ‘subtle and complicated’. He took as a structural model Thornton Wilder’s The Bridge of San Luis Rey, but drew also on his own practice as a novelist.

In the annals of second world war literature, Hersey’s Pulitzer Prize-winning A Bell for Adano (1944) was the first novel to broach ‘postwar reconstruction’. Four years before The Naked and the Dead, it also took shots at America’s military brass. In 1950, The Wall was early to the Holocaust as a subject and formally innovative — a pre-Capote ‘non-fiction novel’, wrote the critic Herbert Mitgang.

If novel-writing enriched Hersey’s reportage, Treglown is percipient on why toggling between them didn’t redound to their mutual benefit. Early recognition notwithstanding, the prodigious research that informed his nonfiction encumbered his fiction, while the empathy he brought to the former tended in the latter towards mawkishness. Treglown spotlights works that still stand up, but it’s hard to escape an impression of an oeuvre marked by worthy, improving tomes whose chief interest today is as ‘cultural-historical’ artifacts.

Hersey might have anticipated Hunter S. Thompson, but — a model of industry, probity and moderation, who kibitzed with President Truman, wrote speeches for Adlai Stevenson and served as master of a Yale college — mad, bad and dangerous to know he was not. He was no milquetoast though, besting J.F.K. to win the affections of Frances Ann Cannon, who became his first wife, and biting the hand at the 1965 White House reception for artists, descanting on the perils of escalation in Vietnam to prick ‘the conscience of the man who lives in this beautiful house’.

This from ‘not exactly an Abbie Hoffman type’, snickered Dwight Macdonald, whose ding on Hersey’s work as an exemplar of the slurry of middlebrow Pablum he designated ‘midcult’ is absent here. Macdonald’s argument has aged about as well as some of Hersey’s novels but, preceding Hersey to Yale and Time-Life before joining him as a New Yorker contributor, he offers a fascinating, if irredeemable, counterpoint to Hersey’s editorial credo. ‘To stick to serious, negative, unconstructive criticism takes… thought and effort,’ Macdonald wrote. ‘The undertow pulling the critic into the dangerous waters of positive, responsible thinking seems to be getting stronger every year.’

Instead, Treglown reaches for boiler-plate about ‘what the 45th president stands for’ to throw the nobility of Hersey into sharp relief. The reality — a man who reproached himself for ‘ambition and vanity’, whose nonfiction was fired by a ‘personal quest’ — is infinitely more interesting than such a morality play.

This article was originally published in The Spectator magazine.