James Shapiro, a distinguished Shakespeare scholar, has turned his attention to the seeds of today’s culture wars in this fascinating, timely and deeply researched book. He unearths them in the demise of the New Deal’s Federal Theatre Project, brought down by a Red-hunting congressional committee. Shapiro’s is an unexpectedly gripping tale, as he exposes the “playbook” of the Texas Democratic congressman Martin Dies, a white supremacist and glory hound who seems to have settled on destroying the Federal Theatre simply as a means of boosting his profile, while also exploring the relationships between politics, plays and propaganda.

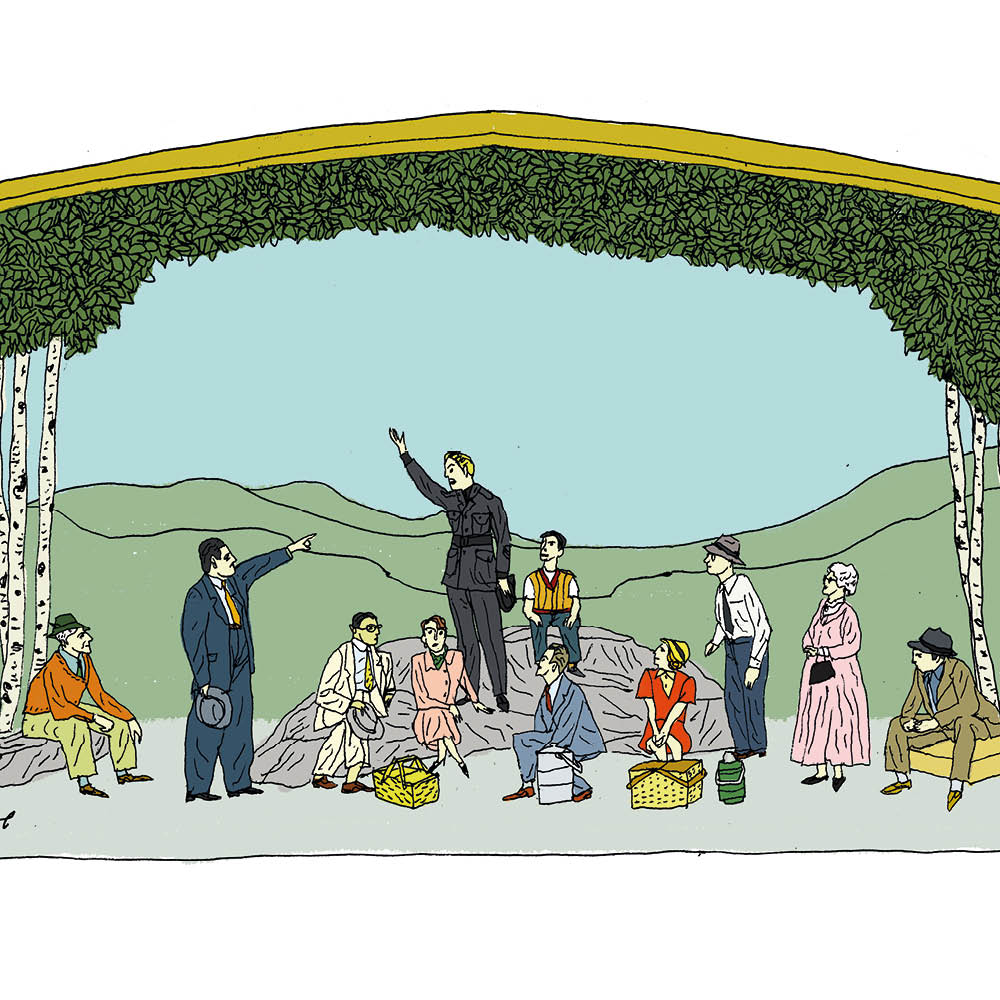

The Federal Theatre was a utopian project of galactic size, of a kind which, in these days of funding cuts, now seems impossible. Its very existence embodies important questions about the commercial viability of the arts as against the necessity of governmental support. During the Depression, Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal sought to boost employment, among other ventures allocating $27 million to its Federal Project Number One for the arts, $7 million of which (a relative pittance) was earmarked for the fledgling Federal Theatre. Directed from Washington, this organization would stage productions across the country, employing thousands, and produce plays that would both “justify the expense and quiet critics,” while reestablishing the theaters that had, until the arrival of the cinema, been vital components of American life.

Chosen to run it was Hallie Flanagan, a Vassar teacher and playwright who had traveled in Europe and, crucially, in Soviet Russia, where she had learned new dramatic techniques and, in the USSR, been piqued by the “intellectually rigorous theater committed to education and propaganda.” Sadly, these tenuous links to communism would be later pounced on by the program’s denouncers, despite the fact that Flanagan remained unpartisan, and that the political scope of the Federal Theatre’s productions ranged widely.

Shapiro details the vicissitudes of the Federal Theatre Project with an eye for irony and vivid detail. In its early days, in 1936, it staged a play in Nebraska. The townspeople, oversaturated by exposure to the movies, had all but forgotten what theater was: 90 percent of the audience couldn’t believe that the actors were not moving pictures, waiting after the performance to see “whether the people are real.”

The Federal Theatre’s production of Ethiopia in 1936 was to have been the first of its “Living Newspapers,” which dramatized current affairs. Arthur Miller called these “the only new form that was ever introduced into the American theater.” Ethiopia, which concerned Mussolini’s invasion of the country, was everything that the Federal Theatre wished: “experimental, collaborative, and politically engaged, with an interracial cast that wasn’t reliant on star turns.” Yet here was an early sign of what was to come. It is one of the many ironies of this story that when a journalist tried to obtain a recording of a Roosevelt speech for use in the play, the State Department informed Flanagan that “no one impersonating a ruler… shall actually appear on the stage.” The production was closed after one dress rehearsal. I don’t know if anybody ever asked Roosevelt’s opinion.

Commercial and critical success soon arrived, however, with an all-black production of Macbeth, staged in Harlem and with a certain Orson Welles, just twenty years old, at the helm, shouting out directions through a megaphone. The action was transposed to Haiti, with voodoo providing the supernatural framework.

Welles worked twenty hours a day, spending his money on “food and taxis… on handouts or loans to company members… on props (including Macbeth’s severed head), and the rest entertaining his male lead, Jack Carter,” in clubs and brothels. The play was a hit, with thousands of Harlemites coming to the Lafayette Theatre on opening night. Welles himself, in 1982, told an interviewer that “my great success in my life was that play,” claiming that he even stepped in and played the role of Macbeth in blackface, though Shapiro drily notes that “no newspaper or member of cast ever confirmed” this. Its reception among critics of all stripes could be used in any discussion about racism, cultural appropriation and the theater, with black critics saying that the focus should be on black plays by black playwrights, and white critics belittling and patronizing the black actors.

Another touchpoint was a production of Sinclair Lewis’s bestselling novel, It Can’t Happen Here, which imagined a fascist takeover of the US. As MGM had canceled the film version (“A movie depicting the erosion of democracy through official censorship was itself censored”) the Federal Theatre staged it across the country, hoping that the productions would “alert all Americans to the totalitarian dangers that film censors preferred to keep from them.” Shapiro invests these proceedings with tension. It was a logistical nightmare, with a mere two months to prepare. Nothing was ready until the very last minute, but the show opened in eighteen cities on October 27, 1936, eventually reaching more Americans than had bought the novel.

The Federal Theatre, then, did have political purpose, and it did stage many plays about pressing social issues which deeply affected ordinary Americans. Yet its treatment of an innovative play, the “Living Newspaper” Liberty Deferred, written by two black playwrights, Abram Hill and John D. Silvera, shows it had other problems. Liberty Deferred dramatized racism in startling form, including a scene in which the hero visits Lynchtopia, an afterworld where the victims of lynchings compete over the brutalities of their attacks. The play itself, however, became a victim of racism. It was edited and mutilated beyond parody, its vitality sapped, its radical message muted; in the end, it was never staged, a symbol of what might have been.

If there is a villain of the piece, it is Martin Dies. He was the first politician in the US to understand the potential of mass media, and thus set off, in Shapiro’s view, the beginning of a publicity parade that ends with the QAnon Shaman on Capitol Hill. Vehemently against the New Deal, Dies quickly learned how to play to press and public anxieties. Stymied in other efforts to further his political career, Dies lit upon convening a committee to investigate “un-American activities” (he cast a wide net) as a way of gaining political power and prestige.

There was enormous opposition to this plan, and Shapiro lifts the lid on the horse-trading and apathy that eventually allowed the formation of the House Un-American Activities Committee. Though initially promising not to turn it into a smear campaign, Dies soon did, flinging accusations of communism willy-nilly. His incompetence was staggering: although he subpoenaed an actual Nazi propagandist, Dies then allowed him to visit Germany, and on his return to the US never interrogated him, leaving him to be exposed later by the Department of Justice. Another of the astonishing ironies of this grim proceeding is that Dies’s New York colleague Samuel Dickstein was being paid a retainer by the NKVD at the same time he sat on the committee, having promised to pass on secrets.

Dies fell upon the Federal Theatre Project as a suitable prospect for investigation almost by accident. His star witness, Hazel Huffman, was a stool pigeon who opened Flanagan’s mail in search of communist references, and her cherry-picked testimony led to mass media coverage. Dies had learned a lesson: scaring people is far “more effective than the arduous and consensus-building business of legislating.” He had become a director, staging the committee as a means of dramatizing his own views, and propagating his message through radio and the press.

His attacks worked, and the Federal Theatre Project had its funding pulled in 1939, after a mere four years. In response, a production of Pinocchio on Broadway altered the ending: Pinocchio dies, and the cast, as the set was taken away around them, intoned: “Thus passed Pinocchio… killed by Act of Congress.” A powerful image, although it’s a shame they hadn’t quite had the time to think about the implications of symbolizing the Federal Theatre as a puppet.

In many ways, The Playbook tells a desperately sad story: the vindictive attacks of one man, aided by politicians who had no understanding of theater (one even asked if Christopher Marlowe was a communist and speculated that “Mr. Euripides” taught “class consciousness”), managed to bring down an organization with noble aims that had the potential to inform, challenge, delight and educate a nation.

While Shapiro is wistful about what might have been had the Federal Theatre Project survived, he’s also realistic about its internal problems: it wasn’t strong enough in defending itself and was too slow to come to Flanagan’s aid. She went back to teaching at Vassar and died thinking her life had been a failure. Meanwhile, Dies’s political career foundered, but he already had established the means by which future generations would fight the same wars, and his legacy lived on.

The Playbook is a dramatic tale, full of overreaching ambition, dastardly plots, embattled heroes and last-minute reversals. It would, indeed, make a fine play about the importance of political plurality, innovation and creative freedom in the arts. In a world where censorship and bans from left and right occur more and more frequently, this cannot be restated too often.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s August 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply