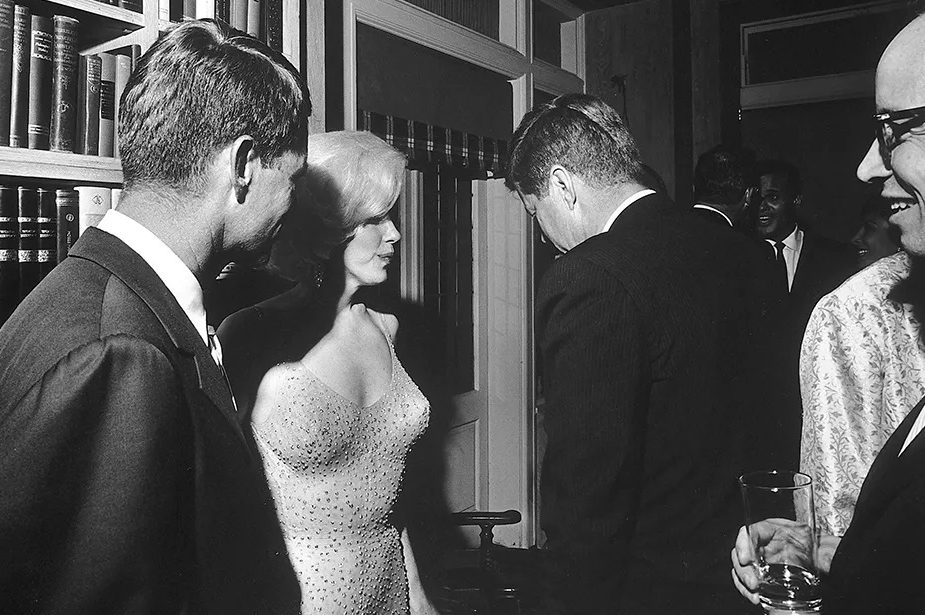

Los Angeles, August 1962. PI and extortionist Freddie Otash is snooping on Marilyn Monroe for labor leader and racketeer Jimmy Hoffa, who’s paying good money for dirt on Jack and Bobby Kennedy. Is Jack really schtupping Miss Monroe? Who cares? Make it so.

But the operation is rumbled and then Monroe dies of an overdose (or does she?) and Otash finds himself pushed from pillar to post by greasepole Pete (Pitchess, 28th Sheriff of LA County) and ratfink Bobby (US attorney general Robert Kennedy), for they too have a stake in filthing-up the film star’s name. Maybe, through it all, Otash can find who and what really got her killed — but not without betraying the woman of his dreams (the Kennedys’ sister Pat Lawford), or facing up to his great weakness (which, this being Ellroy, is obedience to powerful figures even less principled than he is).

This entire book is one gleefully violent foul-mouthed research note. It’s vivid, gripping, surreal

So another chunk of post-war West Coast history descends screeking down the Ellroydian waste disposal, in a book you will have to devour at speed lest in its violent madness it devours you — the latest in Ellroy’s planned new “LA Quintet” and the third in the sequence after This Storm. Never mind the labyrinthine plot (Ellroy is a writer you don’t so much read as investigate); pop to the prose. His signature telegraphese has never felt more naturalistic, ensuring him perpetual squatter’s rights in that stylistic flophouse thrown up by James Caine and Dashiell Hammett.

Ellroy is not without his issues, of course. No need to fret about the drug-pickled corpse around which his delirious noir entertainment churns. No need to take on the burden of her aggravating stupidity, or think your way into her last miserable minutes. She’s Marilyn Monroe, which means you’ve already seen her in a film or read about her in a book; you know Ellroy’s Marilyn is neither your Marilyn, nor the real Marilyn; and so you know we’re just playing charades here, that every punch is telegraphed and every drop of blood is jam.

Otash is a historical figure, too. So’s everyone. There’s next to no one in The Enchanters’ cast who doesn’t have their own Wikipedia page. And just because this approach is classic Ellroy doesn’t stop it from being a mistake.

This entire book is one gleefully violent, foul-mouthed research note. It’s unputdownable, vivid, gripping, surreal, and it’s also, at a spiritually corrosive level, untrue, in a way that fiction need never be.

“Jimmy, Jimmy, Jimmy,” as some goon in The Enchanters might sneer, yanking the strappado, “why give yourself this pain? You’re supposed to lie.”

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.