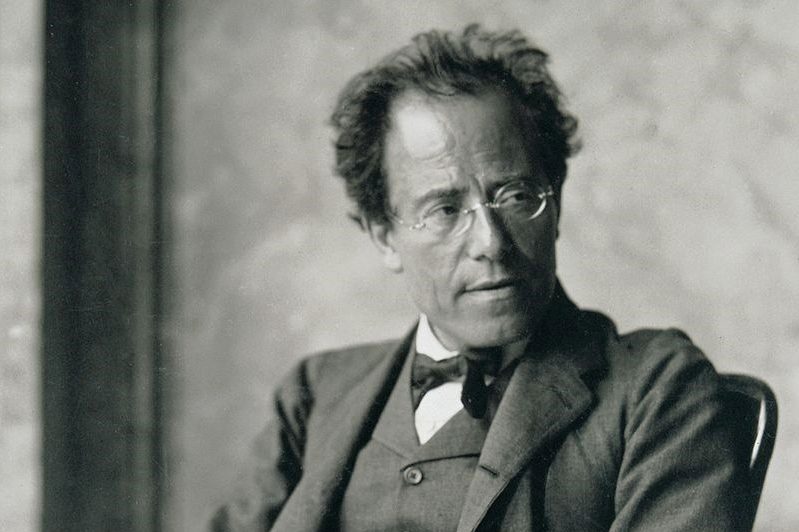

The arc of Gustav Mahler’s career was staggering. Born in 1860 to a poor Jewish family in Bohemia, through tenacity and talent he climbed to dizzying heights, nabbing the conductorship of the Vienna Hofoper, New York’s Metropolitan Opera and the New York Philharmonic. He became a celebrity, hounded by paparazzi as he zipped back and forth across the Atlantic by steamer, a forerunner of today’s globetrotting conductors with their NetJet commutes.

Yet Mahler was plagued throughout his life by nagging existential fears, serious illness and marital strife. He poured this angst into his composing. “Why have you lived?” Mahler wrote in a letter to a friend. “Why have you suffered? Is it all some huge, awful joke? – We have to answer these questions somehow if we are to go on living – indeed, even if we are only to go on dying!” Stephen Downes’s new book, Gustav Mahler (Critical Lives), by approaching Mahler’s life via chapters on six distinct roles the composer played (reader, conductor, husband, etc.), reconstructs the intellectual currents that flowed through Mahler’s creative life and gives insight into the mind of this most psychologically charged of composers.

Psychoanalyzing the composer and his music is a parlor game that far predates the Mahler revival sparked by Leonard Bernstein in the 1960s, when Mahler’s symphonies reentered the repertory and record-store classical sections swelled with Mahler LPs boasting groovy, psychedelic cover art to draw in the Woodstock set.

Sigmund Freud himself took a walk with Mahler in 1910, diagnosing the composer – who was born to a Mary and married to an Alma Maria – with a “Holy Mary” complex, meaning that he idolized his wife as a saint, to the point that he could not bring himself to sate her prodigious sexual appetite. Mahler wasn’t buying it, but the two men found plenty else to discuss – the walk went on for four hours.

Downes’s chapter on Mahler’s favorite writers is fascinating and helps us guess at the subjects that would have animated the composer’s conversations with his contemporaries. As one might expect, Mahler held Schopenhauer and Nietzsche (whom he set to music) in high regard, though he soured on Nietzsche’s metaphysics as he aged. By contrast, Mahler’s taste in fiction is surprising, and might explain his love of juxtaposing the profound with the burlesque and the strange in his art.

Mahler spurned then-trendy symbolists, expressionists and naturalists. In fact, his reading was conservative even by the standards of the late 19th century – Goethe, Cervantes, Jean Paul, Dostoevsky. Fin-de-siècle eroticism left him cold, and he forbade Alma from reading Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray (1890).Yet he loved writers who experimented boldly with form and narration: E.T.A. Hoffmann, for example, whose The Life and Opinions of the Tomcat Murr (1819-21) purports to be a cat’s memoirs accidentally dropped on the printer’s floor and shuffled into the biography of an eerily Mahleresque composer.

Mahler also adored Laurence Sterne’s Tristram Shandy (1759-67), the greatest shaggy-dog tale set in print, complete with tangents on obstetrics and siege warfare and such extratextual adornments as a marbled interior page, a randomly blank page and a printed scribble. Bruno Walter, Mahler’s disciple, reflected that Sterne’s humor gave Mahler the “antidote for the poisons of life, [without which] he would have been unable to bear up under the tragedy of human existence.” As Mahler told the Finnish composer Jean Sibelius on another famous walk-and-talk, “A symphony must embrace the entire world.”There seems something particularly Shandean about that dictum.

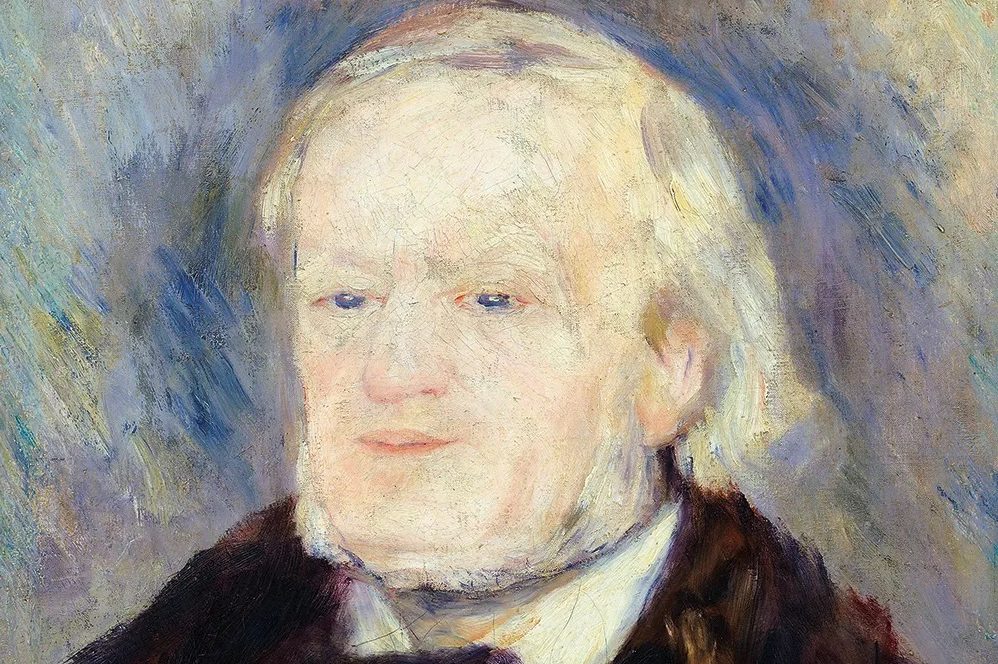

Downes devotes a valuable chapter to Mahler as a conductor, the role that brought him the most fame in his lifetime and that, lacking recordings or video, we most poorly understand today. Inspired by Richard Wagner’s essays, Mahler had no qualms radically re-orchestrating Beethoven or inserting brand-new music into Mozart’s hallowed “Così fan tutte” (1790). Downes helps us see that Mahler can be categorized neither as radical nor a reactionary. He was only his own man, truculent in his refusal to compromise his aesthetic vision. His loyalty was to the spirit – not to the letter – of a composer’s work, and in a manner that would horrify historical purists today. But many in his audience found it electrifying, including an 18-year-old girl named Alma Schindler who, on hearing Mahler conduct “Tristan und Isolde” in 1898, fell in love from afar with all the ardency of a teenage Elvis fan.

Downes sets an illustrative scene for us when Gustav and Alma first spoke with each other at a party in 1901. Mahler, middle-aged and at the peak of his success, found the belle of Viennese society juggling the advances of the director Max Burckhardt and the painter Gustav Klimt. Impatient, the composer butted into the conversation to offer a sardonic point: “Beauty! . . . the head of Socrates is beautiful.”

A surprising number of intimate details survive regarding the Mahlers’ stormy married life, mostly written down by Alma, who had, to put it mildly, rather disconcerting tastes. As Downes shows, you could certainly call Alma an antisemite, though she found herself perversely attracted throughout her life to what she called “ugly,” short, talented Jewish men (she later described one ex-paramour as a “hideous gnome”).

Further complicating matters is the fact that Alma lived 50 years longer than Gustav, which gave her ample time to tell the story of their relationship on her own terms. In this and other matters, Downes does his best to remain neutral, preferring to weigh the varying opinions of Mahler’s biographers through the years. Plenty have found sympathy for Alma, whom Gustav pressured to set aside her ambitions at composing, a source of much critical contention today.

Mahler died in 1911 of a heart infection that, only a few decades later, could have been cured with a round of antibiotics. Morbidly, Downes shows that watching Mahler’s body and health became a spectator sport – critics often fixated on his “nervous energy” and “emaciated” figure on the podium, sometimes in antisemitic terms, though Mahler was in fact obsessed with diet and exercise. His final journey from New York to Paris and then Vienna was described by friends and the press in terms of Christ’s passion: paparazzi mobbed the train car to get a look at the slowly dying man; after he had breathed his last, Alma recalled: “he was washed and his bed made. Two attendants lifted his naked emaciated body. It was taken down from the cross.”

Mahler, who had what one biographer called “a lifelong romance with death,” did much to anticipate this posthumous response, which continues to this day with what Downes calls the “medicalizing” of Mahler’s music in search of hints of dying and illness (Bernstein claimed to hear Mahler’s failing heartbeat in the Ninth Symphony.) Perhaps the answer lies in Mahler’s own words, written for the last movement of the Second Symphony, classical music’s grandest finale: “I shall die, in order to live!”

Is that the slightest hint of a grin on Mahler’s death mask?

Leave a Reply