Baz Luhrmann’s latest exercise in excess, a new biopic of Elvis Presley, called simply Elvis, opens across American theaters this weekend. As ever with Luhrmann, it’s a mixture of sensory-popping provocation, cartoonish performances (Tom Hanks’s Colonel Tom Parker is written and played as if he’s walked out of a Snidely Whiplash short), an eclectic soundtrack and, once the sturm und drang settles, a surprisingly conventional account of a decidedly unconventional man.

Played with chutzpah and charisma by Austin Butler in what must be a star-making performance, Luhrmann’s Elvis is less the bloated, drug-addicted behemoth of latter days than a youthful, hip-swivellin’, groin-thrustin’ icon. But as is the norm now, Elvis is also portrayed as a fundamentally decent man, alive to concerns of his stealing music from black artists and devastated at the news of the death of Martin Luther King. It’s not quite the absurd whitewash that Bohemian Rhapsody gave Freddie Mercury, but there’s still a definite sense of Luhrmann (who, bizarrely, has awarded himself two separate screenwriting credits) portraying his version of Elvis. Any similarities to anyone living or dead is purely coincidental.

There has been a pent-up appetite for a big film about Elvis for decades, and Luhrmann gives people what they want. The 159-minute movie will undoubtedly be a hit. That’s not least because the last mainstream depiction of Elvis was, according to taste, either Jonathan Rhys-Meyers in the 2005 miniseries Elvis: The Early Years — featuring everyone’s favorite eccentric actor Randy Quaid as Colonel Tom — or Kurt Russell, in a star-making role, in the 1979 John Carpenter-directed TV film Elvis. You might say Carpenter was the perfect filmmaker for the project, given his previous depiction of a blank-faced sociopath who creates havoc in the lives of young women. It doesn’t seem too much of a stretch to go from Halloween’s Michael Myers to the darker incarnations of “the King of Rock and Roll.”

Not that you would know this from the various films that Elvis himself made. The irrepressible Colonel, who was aghast at the idea of his protégé leaving the country — rumor had it because Parker was liable to be arrested if he emerged in various European nations — instead hit on the idea of Presley appearing in cookie-cutter pictures. These would then allow foreign audiences to see their idol vicariously, rather than bothering with any admin-sapping foreign tours.

Between his debut in 1956’s Love Me Tender and his final feature role in 1969’s Change of Habit, Elvis appeared in 31 films as well as various documentaries and concert pictures. Some of the early ones, not least 1957’s Jailhouse Rock and 1960’s Flaming Star — the latter of which actually allowed Elvis to act, rather than play a variant on himself — stand up well today. But the Colonel’s determination to force Elvis into the straitjacket of insipid musicals with unfortunate titles like Girls! Girls! Girls! saw him become increasingly bitter about his cinematic standing. He complained that he was only appearing in the B-movies for his manager to make money. He was correct.

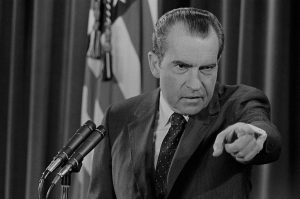

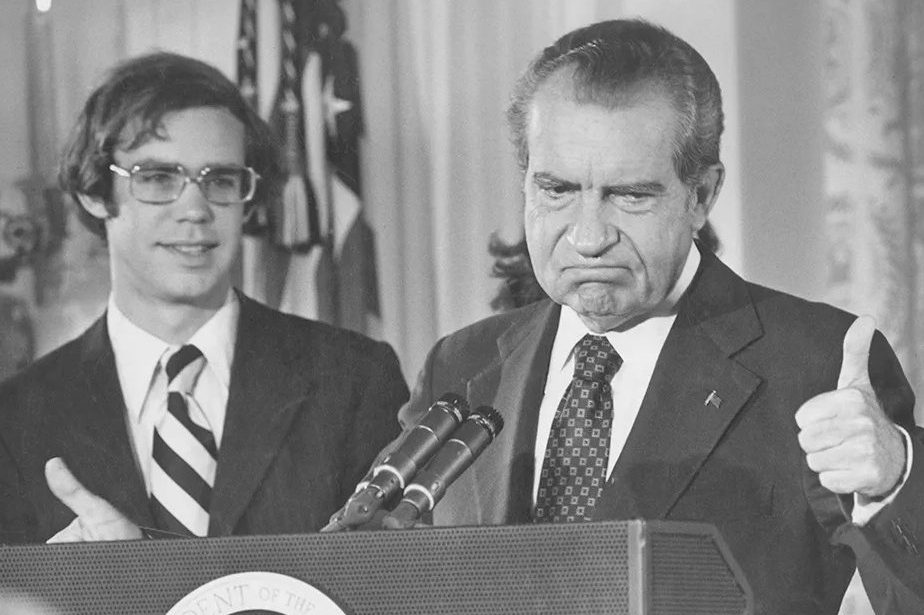

Luhrmann’s film deals with all of this, but in cartoonish, broad-brushstroke detail. While it’s an enjoyable enough evening at the movies, one longs for a more credible treatment of a strange and contradictory man. The surreal incident when a pill-popping Presley offered his services to Nixon as “Federal Agent at Large” in his fight against communism and illegal drugs is nowhere to be seen (although the film Elvis and Nixon, starring none other than the disgraced Kevin Spacey as Nixon, depicted the unlikely relationship for the two men).

Yet the rise and fall of Elvis is a topic that is, perhaps, too grandiose for conventional cinema. Maybe it’s time for the King to be given his true recognition. I can see it now: Elvis: The Opera. Let’s hope it comes to pass.