‘I like your shirt today,’ Sir Ray Davies says to the waiter who brings his glass of water to the table outside a café in Highgate. ‘How’s your girlfriend?’ It turns out the girlfriend is no longer the girlfriend. ‘You broke up? You know, that happens. It’ll be OK. You’ll meet somebody else.’ He pauses and then says something that runs through my head for days after our interview. ‘She’ll meet somebody else.’

It’s true, of course; she will. And it’s a human thing to say: both parties to the relationship will move on. But it’s also delivered with a hint of claws. Who wants to be told, fresh from a break-up, that their ex will soon be hooking up with another partner? It seems like a very Ray Davies thing to say, given that so many of the songs he wrote for the Kinks seemed pretty and straightforward, but left scratches.

Davies speaks so softly that cats wouldn’t hear him coming. There are times I can’t make out what he’s saying, and when I play back the recording those passages are indistinct murmurs. Maybe they’re the bits where he says what he really thinks, because he’s adept at taking one question and answering another. You might think that he’s a slightly doddery, slightly forgetful old gentleman, but I don’t believe that for a second. Those kinds of chaps don’t release two albums in a little over a year (Our Country: Americana Act II, the second of a pair of records to accompany his 2013 autobiography, comes out on 29 June.) And as Davies himself observes when mentioning the old, unrecorded songs that are shunting unbidden across his mind as he prepares a box set of the 1968 album The Kinks Are the Village Green Preservation Society: ‘I’ve got dementia in reverse.’

For all his reputation as one of England’s defining pop songwriters, America was Davies’ inspiration, and it is to the subject of America that he has been drawn these past few years. America came into his life from ‘listening to records. My sister lived in Canada, and she used to send early pressings of Elvis Presley, Carl Perkins, before they came to the radio in England. And films, of course. It was an accumulation of everything that postwar austerity in Britain didn’t have. Britain was broke after the war, and America seemed rich, affluent. It represented freedom, to aspire to the good people wearing white hats, the bad guys wearing black hats. By the time we got there [in 1965] we found it quite different. I’d say it was more right-wing when we first toured than it is now.’

I mention how it’s still a thrill when the plane comes down to land at JFK. He says he prefers to be on the ground, then remembers sitting behind the soul singer James Brown on a flight when the landing had to be aborted. Brown sat up and hollered out, in character as the Godfather of Soul: ‘Good GOD!’

Does he still love America the way he did when he was a young man? ‘I never loved America. I was in awe of it. Shocked by it. Astounded by its versatility. Never loved it.’

Yet Davies went to live there in 1998, dismayed by Tony Blair (he couldn’t work out what Blair represented), and he ended up getting shot and nearly dying in his adopted home of New Orleans. So if he doesn’t love it, why is he drawn back to it as a subject? ‘Because it’s endless. You think you’ve discovered it, but there’s always something around the corner. You get in the car and you drive, and there’s a whole new culture. In Minnesota you’ve got the Swedish people, in Wisconsin you’ve got the German people. In the desert you get Navajo Indian. I think it’s because you’ve got the landmass to accommodate all these cultures.’

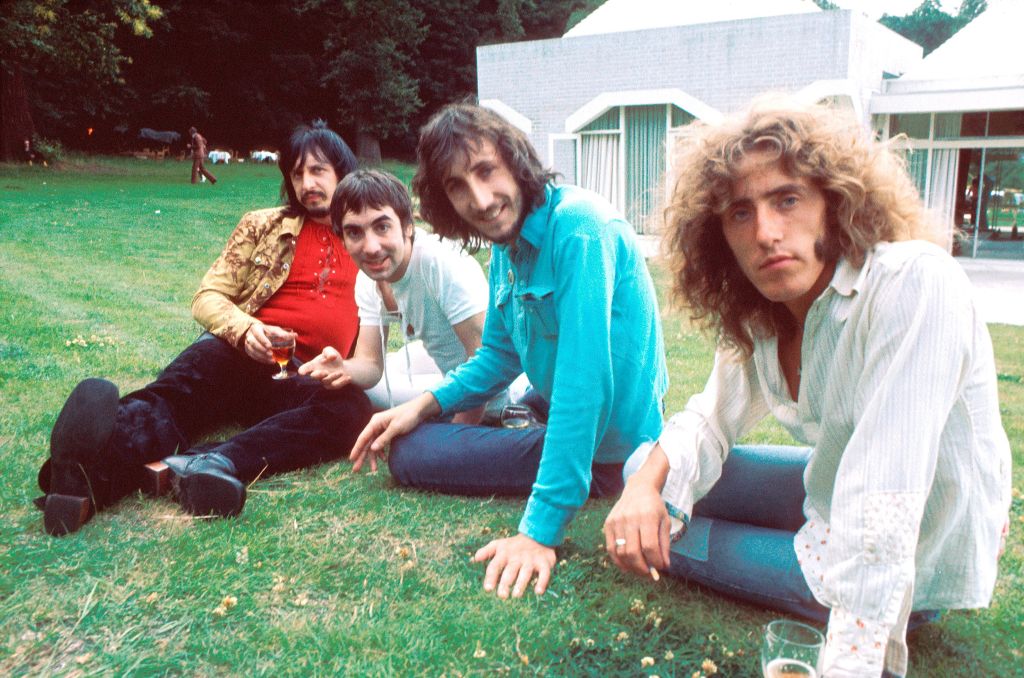

The Kinks’ greatest period had little to do with America, though. Having made their name in 1964 with ‘You Really Got Me’ and ‘All Day And All Of The Night’ — songs so good Davies says he felt no need to compete in the Stones/Beatles/Who pop arms race, since he’d already surpassed them — the band went to America in 1965 and were promptly banned from the country for four years, officially for not paying union dues, though Davies always suspected their bloody-mindedness was the real cause. Back home, Davies set about writing the barbed and wistful portraits of England that are the bedrock of his reputation as a writer: songs such as ‘Sunny Afternoon’, ‘Dedicated Follower Of Fashion’, ‘Waterloo Sunset’, ‘Autumn Almanac’, albums such as Something Else by The Kinks and Arthur (Or the Decline and Fall of the British Empire).

On returning to America in 1969, he was at last able to pursue transatlantic rock stardom. He didn’t enjoy it much. ‘I think the Kinks could have found a better frontman,’ he says. ‘I’d like to have just written the songs, then given them to someone else to sing.

‘The Kinks didn’t get along very well, but we had the ability to interact musically, and for three minutes, to make a record, everything was thrown out, all the hatred would go.’

And how would an old-fashioned rock star have survived had #MeToo been around in those days? Davies sidesteps this one. ‘A world-famous groupie once threw me out because I was too kind. Then this wonderful woman came over from LA to see me. She turned up in an evening gown and I took her to a fish and chip shop. I’m not an easy date. When we went back to America in the early 1970s after the ban, if you were a gentleman to a woman you were considered uncool. Although the grotesque revelations about Weinstein were appalling.’

But that’s how power works, I suggest. People behave towards power in the way they are expected to. And rock stars represented power within their own world. He talks again about 1970s groupies, then mentions he had seen a discussion about Weinstein on Newsnight, with an American actress — he means Rose McGowan. He doesn’t sound awfully impressed by her. But surely it is better to talk about this than let it fester?

‘Obviously, she felt damaged and unjustly treated. All these things, it’s the cycle of life.’

As for Brexit, he will not be drawn even on whether he voted in the referendum, and the thoughts he will offer could support either side. ‘The next couple of years is going to be an immense period of change, not just in our country but through Europe. It’s an immense change, and the generation coming through, the millennials, will feel the impact of it,’ he says. ‘I think it’s the most significant event since the end of the second world war. I’m not a politician, but my instinct is that we’re going to have to reassess our identity for ourselves.’

Sir Ray Davies has just turned 74. He still loves the view over London from Primrose Hill at five in the morning, and mentioning it sets him on a reverie. ‘I still think of a girl I turned down in Paris all those years ago. She called me every name under the sun but I didn’t take her back to my hotel. I remember it was five in the morning, and I said I was going. Images like that stay with me. I like New York on the Thanksgiving Day parade, which used to go past my apartment on West 72nd Street. What was really enjoyable in the 1980s was that I lived in central London, on Luxborough Street, off Marylebone High Street. I had a flat. At weekends we would go out on our bikes and cycle all round London. Loved that.’

He takes a sip of a glass of red wine, and puts it down, still almost full. His driver is here to take him back to Konk Studios, up the road in Hornsey. He has a song to record, an American newspaper to talk to. The autumn almanac of Ray Davies continues to fill up.