Lately you may have noticed a conspicuous absence of pop stars ostentatiously cavorting and doing stupid stuff. This is for two reasons. One, the great distraction that is the entertainment industry — ‘The Spectacle’, as the French provocateur and Situationist Guy Debord called it — has been turned off. Two, the Pop Star currently has nowhere to do his or her pop thing.

This is not for want of trying. During the early days of the pandemic, a battalion of pop stars fled to the internet to broadcast acoustic renditions of their new wares from their terrible minimalist homes. This culminated in the horrendous One World Together at Home concert. Eight hours of pop stars trying to convince the world that self-isolation wasn’t so bad (and is even tolerable if you live in a 25-room mansion in Laurel Canyon). Highlights of this unexpected comedy extravaganza were Madonna broadcasting messages of hope from a candlelit bath of asses’ milk; Lady Gaga miming with her microphone the wrong way round; and Elton John doing an unintentional impersonation of the outsider rockabilly god Hasil Adkins. None of this was altruistic. One World Together at Home was hype, selling product that would otherwise have gathered dust in a warehouse.

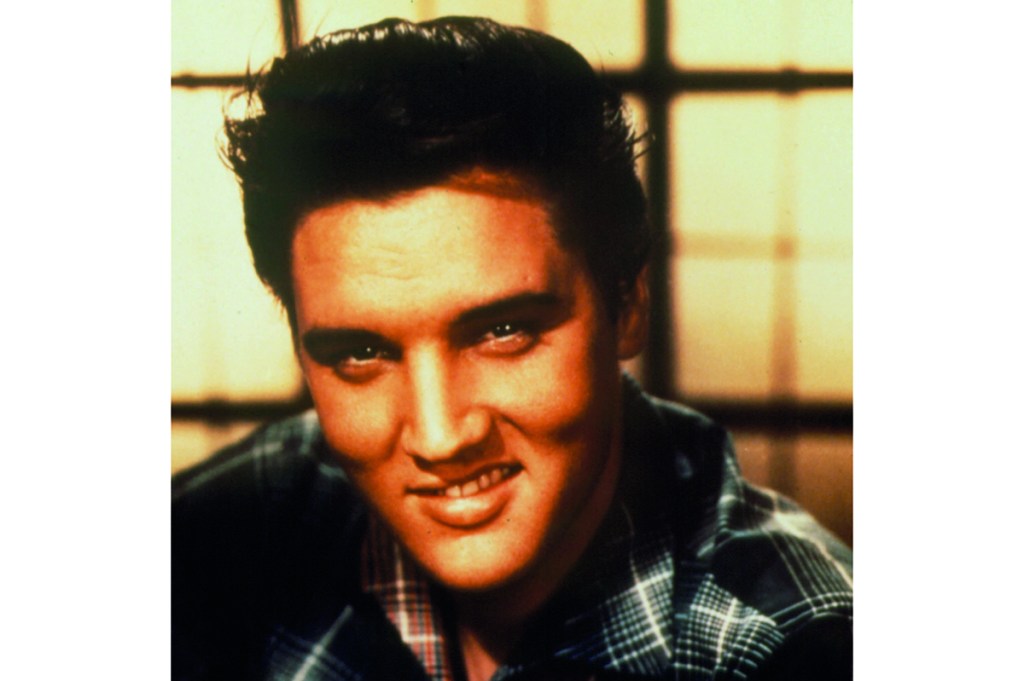

Where there’s pop, there’s hype — and there’s nothing wrong with that. In the Forties, Sinatra made the Bobby Soxers moist. By 1952, Johnny Ray drove them to genuine hysteria as he fitted and sobbed his way through ‘Cry’. Then King Elvis stole Johnny’s thunder. But what came first, the hips or the hype? Elvis did the equation: the hips were the hype which generated the hysteria, which earned the filthy lucre.

Modern pop music was born. The Beatles mainly managed to avoid charges of hype. The only slips came early on with the made-up, self-conscious language, ‘gear’ and the long-forgotten ‘grotty’. By 1963, the screaming fans were real. Still, a band could come unstuck through hype. The great Brit band the Move, who later became ELO, were an early victim. When Move manager Tony Secunda packaged their smash single ‘Flowers In The Rain’ with a postcard of Prime Minister Harold Wilson in bed with his secretary Marcia Williams, Wilson sued and won. The Move made brilliant records for a brief period but never lived the incident down.

In 1970, Nick Lowe was a member of Brinsley Schwartz, a decent but out-of-step English version of the Band (really!). Brinsley’s manager, Dave Robinson (later to found and hype Stiff Records) nabbed the unknown Brinsleys a spot supporting Van Morrison at the Fillmore East. The hype was to fly a swarm of British journalists to New York to see the show, giving the hacks a freebie and thus guaranteeing fantastic reviews. Unfortunately a delayed plane delivered an irritable stew of drunken and hungover journos to witness an unrehearsed Brinsley play a poor show on unfamiliar rented equipment. Reviews were terrible, and the band were done for.

Nick Lowe turned up a few years later as a welcome, wiseacre elder statesman of punk. At which point it would be remiss to not mention the Sex Pistols. ‘The Sex Pistols were just a load of hype!’ goes the departing cry of elderly, infirm men as their families joyfully deposit them in a nursing home to ponder the irritant that was punk. Was it the hype or the hip swivel, or the ‘hip young gunslingers’ of the English music press, that created the Sex Pistols?

According to their mismanager Malcolm McLaren, the band were a piece of human art which he manipulated as ‘living sculpture’. I buy that to a degree, but you couldn’t make up green-haired, 19-year-old Hawkwind fan John Lydon wandering into McLaren’s boutique and miming to Alice Cooper’s ‘Eighteen’ like a pantomime Richard III.

My own dalliance with hype occurred in the late 1990s when one of the outfits I was in, Black Box Recorder, released our debut album, England Made Me. It was common promotional wisdom back then to send out ‘product’ to ‘influential’ people such as Robbie Williams or Jarvis Cocker who could provide a useful puff quote. We made sure that a copy of our album was sent to the notorious Conservative minister, rake and crypto-fascist Alan Clark.

If you’re unfamiliar with Clark, think of a caricature of an ultra-right-wing, upper-class, pro-hanging, anti-immigrant sozzled lord, and you’re halfway there. Clark lived in a castle with two dogs called Leni Riefenstahl and Eva Braun. We didn’t really want anything from him. We just liked the idea of our record company sending a package to Clark’s home address, Saltwood Castle, which he’d inherited from his father, Kenneth Clark, who is beloved for having hyped Civilisation on TV. Alan Clark is remembered for his shameless diaries, and for making the papers by seducing not just the wife of a judge, but also two of their daughters. He was a busy man, and we never heard back.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s February 2021 US edition.