This article is in The Spectator’s March 2020 US edition. Subscribe here.The topics in

The Necessity of Sculpture emerged randomly, thrown off by successive exhibition calendars and coming to range in time and place from ancient Mesopotamia to 21st-century Manhattan. As I made the selections, what began to take shape, beyond a conventional anthology, was a synoptic history of the art form. The title is a belated riposte to Ad Reinhardt’s famous dismissal, in around 1960, of sculpture as ‘something you bump into when you back up to look at a painting’.

Rosary beads

Some of the most remarkable objects in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s encyclopedic collection are hinged wooden beads about one inch in diameter which open to reveal a Cecil B. DeMille biblical scene carved inside. Imagine Michelangelo’s ‘Last Judgment’ fresco (45ft by 40ft) relocated to the inside of half a golf ball and you’ll have an idea of the head-spinning combination of epic conception and diminutive execution. How have such exquisitely delicate objects, in which Roman centurions wield spears a quarter the thickness of a matchstick, survived the ravages of time?

These rosary beads, made in the Netherlands in the 16th century, are unlike anything in the history of western art. Works created for private devotion, they would be held in their owners’ hands, their scenes contemplated, the religious inscriptions on their carved exteriors read or idly fingered. Some were carried everywhere in a protective case on the owner’s belt. Each hemisphere is not, as was long thought, a single piece of wood painstakingly dug out by its maker. Instead it is a composite of multiple layers or slices of wood — up to eight per bead — each carved individually, the whole bead then assembled and held together with wooden pegs inserted into drilled holes.

Gian Lorenzo Bernini

If the essence of Bernini’s marbles is their jaw-dropping illusionism — their ability to simulate windblown hair, soft flesh, even tears – what distinguishes his preparatory works is their immediacy. They convey the quick flash of an idea and even, in their rough tooling or the vestigial impress of a finger, the very presence of the artist. Marble’s obduracy made form hard-won. Clay’s malleability allowed it to spring from Bernini’s hands almost at the speed of thought.

His swaggering repudiation of all things Michelangelesque is evident in his ‘Model for the Fountain of the Moor’, in the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth, Texas. As with a Michelangelo, we have a well-muscled, upright male nude. But all similarities end there.

Bernini’s Moor strides forward with his left leg, at the same time twisting his torso in the opposite direction and turning his tilting head in a direction counter to that. Everything in the figure that can bend, swivel, tense or flex is made to do so, and musculature is used as a means to an end — dynamic motion — not as an end in itself. In an anything-you-can-do gesture, the Moor’s back is more heavily muscled and his weight-shifting contrapposto pose more extreme than any of the Ignudi on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. Bernini never surpassed Michelangelo — nobody could. But he fought him to a draw of sorts. Alone among artists, Bernini made Michelangelo seem tame, even conventional.

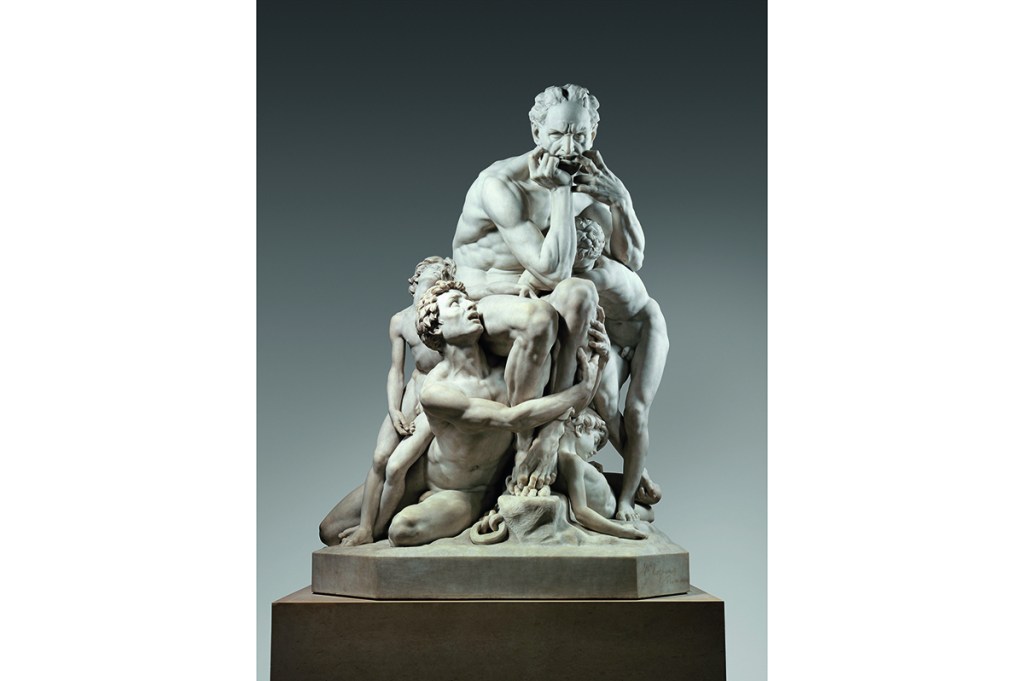

Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux

If Carpeaux is known at all, it is primarily for the life-size marble ‘Ugolino and His Sons’ — long part of the Met’s collection — and for ‘The Dance’ (1869), the bacchanalian group on the exterior of the Opéra Garnier in Paris. But there was far more to Carpeaux than that. He was not an innovator, but his figures reveal more about the swirling aesthetic currents of his day than those lightning-in-a-bottle revolutionaries who, almost by definition, stand apart from their time. Carpeaux’s work reflects both a waning Romanticism and a nascent Naturalism. Despite his strong allegiances to the past, he was enough of an independent spirit to serve as a precursor of Rodin in his free approach to sources and to reconceiving the public monument. Three decades before the outcry at Rodin’s ‘Monument to Balzac’, Carpeaux faced a similar scandal over ‘The Dance’. Deemed obscene, it was splashed with ink by a protester a few weeks after its unveiling.

The subject of ‘Ugolino and His Sons’ is from Dante. The tyrant of Pisa, Count Ugolino della Gherardesca, has been deposed by Archbishop Ubaldini. Walled up in a dungeon with his sons and grandsons, he is being driven to cannibalism. In choosing Dante, Carpeaux departed from the practice of picking a classical or biblical story. In executing the group, he rejected a strictly classicizing approach, his sources instead ranging from past to present, from the ‘Belvedere Torso’ and Michelangelo to Géricault’s ‘Raft of the Medusa’.

Rachel Whiteread

‘Greatest living British artist’ is among the most abused accolades in art criticism. The one person who deserves it today is Rachel Whiteread. Generationally, Whiteread (born 1963) is one of the Young British Artists notorious for 1999’s Sensation exhibition. Temperamentally, she couldn’t be more different. Whiteread is old school. Her art expresses something personal and deeply felt.

‘Untitled (Domestic)’, at the Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh, is some 22ft tall and resembles an asymmetrical V on a base. It is a cast of the negative space of a fire-escape staircase, but it quickly asserts itself as a stunning abstract sculpture, its authoritative presence and audacious forms, one of them boldly cantilevered out and up, ensuring that it commands every cubic inch of the surrounding space. At the same time, its monumentality, truncated appearance and pattern of notchings and surface striations combine to suggest an ancient architectural fragment recovered from some desert ruin.

The Necessity of Sculpture: Selected Essays and Criticism, 1985-2019 is published by Criterion Books ($19). This article is in The Spectator’s March 2020 US edition. Subscribe here.