Many labels leap to mind in association with the prolific and controversial Norman Mailer, who died in 2007, but “biographer” is not typically one of them. He was not considered a serious practitioner of the genre in the same sense as Edmund Morris, Ron Chernow or his friend Doris Kearns Goodwin. And yet, as his own official biographer J. Michael Lennon asserts to me, “Mailer became a major biographer in the last half of his career.”

Thirty years ago, two intriguing books by Mailer appeared just a few months apart: Oswald’s Tale: An American Mystery and Portrait of Picasso as a Young Man. Both were eclipsed at the time by competing treatments of their subjects, but Mailer’s volumes are the highpoint of his idiosyncratic contribution to biography and are well worth a reappraisal.

In addition to his three official entries in the field, including his 1973 Marilyn, Mailer wrote several other books that leaned heavily into biography, among them The Fight, The Executioner’s Song and the biographical novels The Gospel According to the Son and The Castle in the Forest, along with scores of magazine profiles stretching at least as far back as the John F. Kennedy-themed “Superman Comes to the Supermarket” from 1960. If we expand our definition to include these genre-bending portraits, it could be argued that Norman Mailer wrote little besides biography in the second half of his career.

Yet the formal mapping of a life, birth to death (or, in the case of Picasso, birth to age twenty-five) was something Mailer stumbled into by accident. The project that became Marilyn began its life as the preface to a coffee-table volume of Marilyn Monroe photographs. Very quickly, the author got carried away with his assignment, sending the designers of the book scrambling to accommodate its new shape.

There were critical headwinds from the outset, but Mailer brought innovation to his new field. He uses the first-person plural frequently, suggesting that “we” — author and reader — are in collaboration, attempting to piece together a puzzle. This enables him to speculate openly on the inner lives and motivations of his subjects, exploring and discarding theories ranging from the sensible to the far-fetched. It’s a fascinating view into a process that many biographers engage in privately.

Mailer attempted to inhabit historical lives via what we might call “method biography,” which he explained in a letter to Henry Miller after profiling him in a 1976 literary study titled Genius and Lust. As Lennon relates in Norman Mailer: A Double Life:

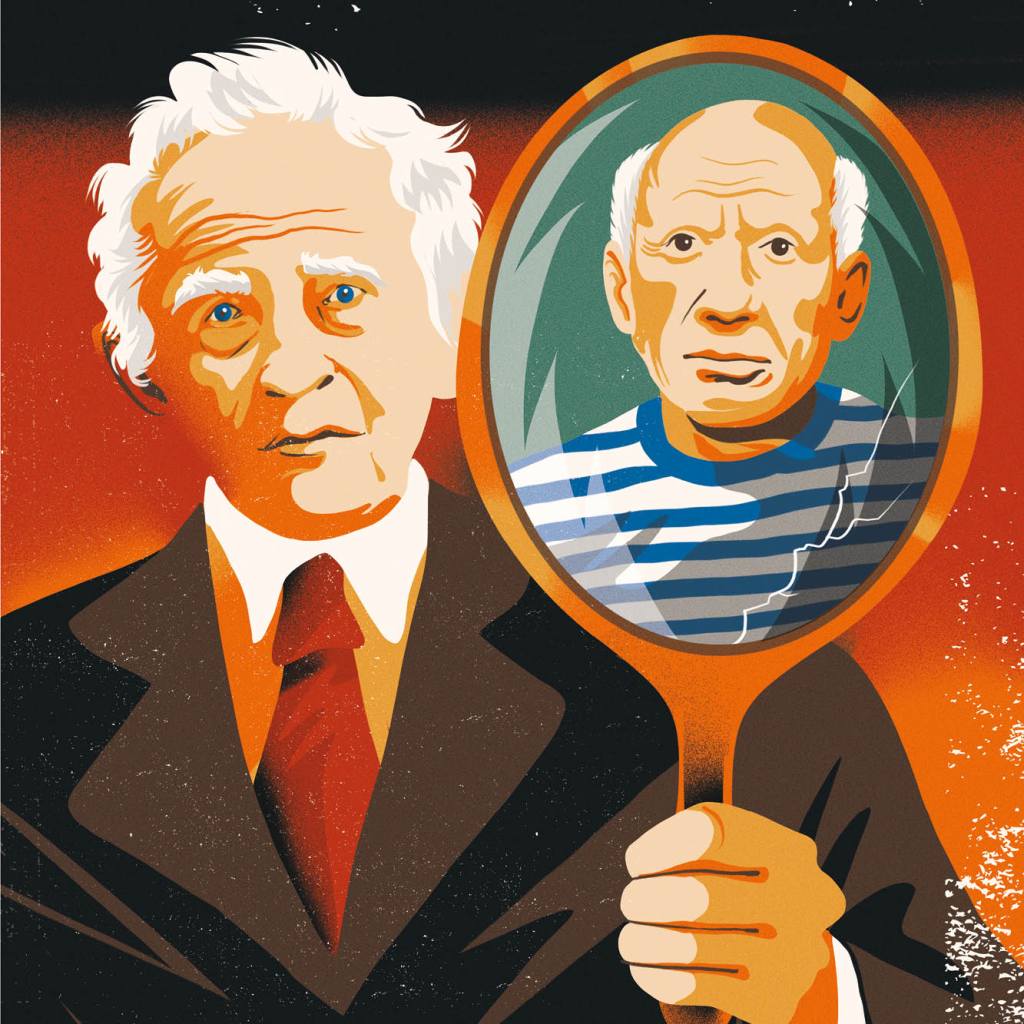

Mailer told Miller that he expected to be attacked by Miller’s supporters and rightly so for “putting much of myself into you. It is the technique by which I work and I’ve never pretended to hide it. When I wrote about Marilyn Monroe I tried to understand her with that part of her I felt was similar to myself. I’ve made the same attempt with you.”

Marilyn, despite its rushed nature, is a lyrical treatment of Monroe’s willful ascent to Hollywood stardom, chock-full of asides on reincarnation, the occult and, most jarringly, Richard Nixon. It is a gloriously weird and compulsively readable book, though whether the author captured the essence of his subject is open to debate. Susan Mailer, a staunch though not uncritical defender of her father’s work, tells me, “I think it’s a book that men love. I haven’t heard many women talk about Marilyn… When I was reading it, I thought, these are Norman’s fantasies about Marilyn. Who knows if she was really like this? It was a free-association kind of biography, and he took liberties.” Arthur Miller, Monroe’s third husband, was less measured in his response, opining that the book amounted to the writer’s imagining himself into it, what Miller called Mailer “in drag.”

Marilyn has its advocates. Carl Rollyson, author of well-regarded biographies of both Monroe and Mailer, has said that reading Marilyn was his impetus for becoming a biographer. “What I liked about it was his musing on biography,” Rollyson tells me. “And obviously he felt he understood certain things about Marilyn Monroe, but he acknowledged that certain things were opaque, that they were hard to get at. I think he got a lot of it right. Norman Mailer revolutionized the biography of Marilyn Monroe, and he did it with one word, and the word was ‘Napoleonic.’ Up until then, by and large, the narrative was of a woman who had a lot of psychological hang-ups and was suicidal and — poor Marilyn, she’s pathetic. Well, you don’t call a pathetic woman Napoleonic.”

Susan Mailer has a warmer take on Portrait of Picasso as a Young man, where she feels that the “method” approach hit its mark. “I loved it,” she says:

I thought it was a great biography because it touched on the human quality of Picasso. Picasso was loved by his mother and was loved by women, as was Norman. He was a little guy just like Norman. He was tough and barrel-shaped like Dad, and he had this unbounded energy. So I think my father saw a lot of points of comparison. As a matter of fact, I remember telling him that I understood him more now. I understood why he was so driven. I understood what he would go through when he had this idea and he was writing, you could never interrupt him or be in his way or anything…. That book really helped me understand him psychologically.

“Mailer was interested in Picasso and Monroe because they were artists,” Lennon notes, “and shaped to a great extent as much by their immense fame as by their art.” From that perspective, their overlap with Mailer’s status as one of the last “celebrity authors” who dominated the cultural conversation of the 1960s in a way that is difficult to conceive of in the 2020s, is considerable. But the insular Lee Harvey Oswald must have presented a greater challenge, and it is fortunate that 1995’s Oswald’s Tale, which functions as both a biography and a true-crime narrative, appeared after 1979’s The Executioner’s Song, Mailer’s immersive, factually scrupulous, Pulitzer-winning account of the final months of murderer Gary Gilmore.

Oswald’s Tale represents a skillful blending of the speculative approach of Marilyn with The Executioner’s Song’s relentless grounding in the known facts. Few would argue that Mailer did not get as deep into Oswald’s psyche as was conceivably possible. Initially, Oswald — whom we first glimpse as an inarticulate would-be defector to the Soviet Union — is defined by his negative spaces: his avoidances, his unexplained acts (and resources), and the trace impressions he leaves on those around him, all of which provide the author a glimpse through an open door that can be nudged wider as details accumulate. As with Marilyn, Mailer invites the reader to join him in considering various possibilities concerning Oswald. But unlike with Marilyn and the later Picasso book, the speculation is grounded in extensive on-the-ground research conducted by Mailer and his research collaborator Lawrence Schiller in Russia, along with a careful parsing of the Warren Report and the other established American sources.

The book ranges across the entirety of Oswald’s life. And it carries some weight that Mailer, not unfriendly to conspiracy theories, ultimately concludes that Oswald acted alone in killing John F. Kennedy. It is also significant that the Kennedy-admiring author locates a point of empathy with Oswald as the unseen needing to be seen — a man seemingly fated for historical insignificance violently wresting the wheel away from fate.

Oswald’s Tale received some of Mailer’s strongest reviews since The Executioner’s Song, though its lukewarm sales must have disappointed. Gerald Posner’s nearly contemporaneous Case Closed: Lee Harvey Oswald and the Assassination of JFK undoubtedly stole some of its thunder. Perhaps too, as Lennon speculates, readers recoiled at Mailer’s “Tolstoyan compassion” toward the purported assassin. “Oswald’s Tale… is another of Mailer’s books for readers a century hence,” Lennon writes in A Double Life, “readers removed from the pain of one of the greatest tragedies of twentieth-century American life.” Still, Mailer’s deeply felt consideration of Oswald’s psyche is of value to the literary-minded student of American history. And there was at least one reader of Lennon’s generation who was able to mine the book’s riches: Stephen King relied on Oswald’s Tale (along with Case Closed and works by Edward Jay Epstein and Thomas Mallon) as source material for his acclaimed Kennedy assassination thriller 11/22/63, calling Mailer’s book “remarkable” in the afterword.

There are obstacles to any contention that Mailer’s biographies are lost classics. The faults of Marilyn and Portrait of Picasso (which received a critical drubbing on its release) are apparent, and the books occupy an eccentric position even within Mailer’s own canon. It is regrettable that Mailer, who had a large family to support and was often in need of quick money, did not have the time to do more original research (Oswald’s Tale excepted). He quotes far too much — pages-long passages — from other authors, which, whether done for expediency or, as he insists in Portrait of Picasso, to capture “each separate vision” of the other authorities, makes the cut-and-paste accusations of some critics difficult to challenge.

But I would argue that Mailer’s efforts go to the heart of why we write, and read, biographies in the first place. We wish not only to learn of the lives of the movers of history, but also, to locate ourselves within their experiences. Norman Mailer was one of the few contemporary biographers to openly lean into this impulse. The doors are still open in these occasionally frustrating, haphazard, yet ultimately alive books, beckoning us on to further exploration.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s January 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply