The fate of the pop musician — at least the pop musician below the top tier of stardom — has historically been to fall from fashion. At some point in their rise they will be of the moment, the spirit of the age, and then they won’t be. At best, they’ll have a slow but perfectly lucrative fade, as their fanbase dwindles to the zealots. At worst they’ll become a punch line, a raised eyebrow: “What were we thinking?” Every hit, every sold-out show, is just another step closer to irrelevance.

‘There’d be 800 teenagers in a club in Minneapolis, which felt absurd: we’re old enough to be their parents’

It may be that the single greatest artistic effect of the Covid pandemic has been to change that. Over the past few years, since we were all locked indoors, groups long since consigned to what Smash Hits magazine called “the dumper” have begun to re-emerge. And all because kids with nothing to do for a year but make TikToks started raiding pieces of old music. The wispy, guitar-led 1990s genre known as shoegaze, for example, has become big business. Look at Slowdive, who reunited to mild interest a decade ago: they found themselves with a top ten album across Europe last year, and headlining festivals in front of real people this summer, after becoming TikTok sensations.

Or take the Canadian band Mother Mother, who had been making records for fifteen years, to widespread lack of interest, until a bunch of their old songs blew up with LGBTQ kids during lockdown. By that point, their singer, Ryan Guldemond, had more or less given up thinking he’d get a second chance at fame. “We had been making valiant efforts to establish ourselves in territories other than Canada, but to no avail. You can only travel down that road so long before you, out of respect for rationality and logic, consider that maybe it is never happening. And so you begin letting go of a dream that includes international success, and maybe there’s a bit of a grieving process attached to that, and at the same time, you feel relief because there’s less pressure.”

During that period of inactivity, he noticed things changing. “We were getting streams and YouTube views, and none of it made sense because there was no obvious breakthrough in promotion. Then our management worked out it was coming from TikTok.”

When the band returned to playing live after the pandemic, they were in the same clubs as before, but everything else was different. “At first, the crowds weren’t thousands, but there’d be 800 teenagers in a club in Minneapolis, which felt absurd: we’re old enough to be their parents.”

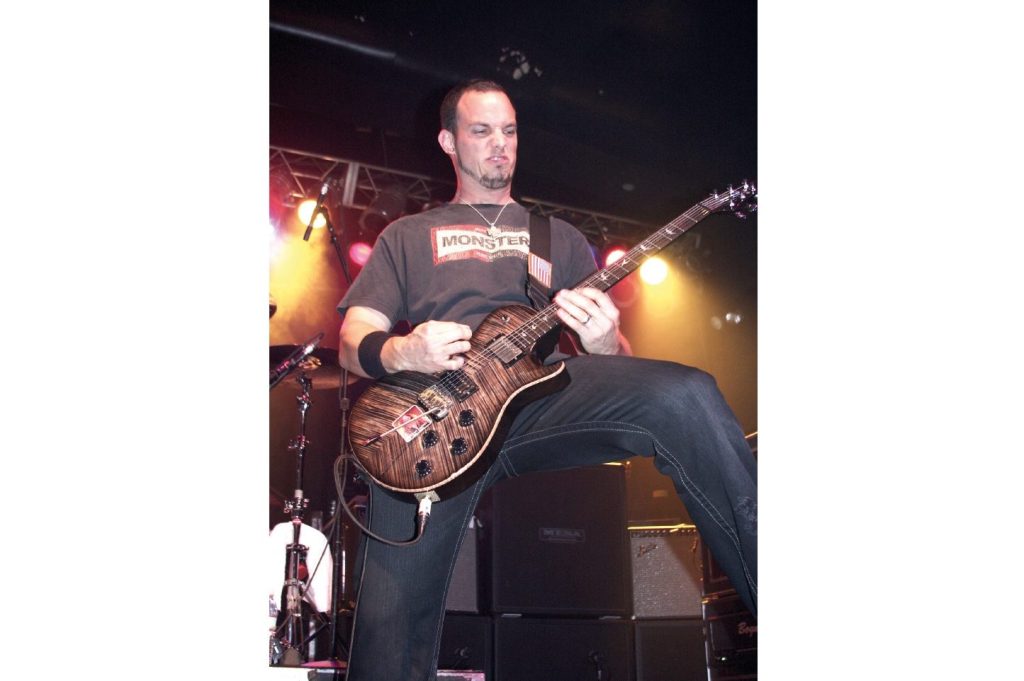

Creed were one of the biggest rock bands of the 1990s and 2000s, selling more than 53 million records worldwide. They then went on to become one of the most derided bands of the following years — a group no one would admit to having liked. But during the pandemic their music started resurfacing, at first ironically: a video clip of them playing the Dallas Cowboys’ halftime show on Thanksgiving 2001, intercut with scenes of 9/11 heroism, started doing the rounds. But then people started liking them for real.

“I didn’t even think too much about that performance for years and years and years,” says Creed’s guitarist, Mark Tremonti. “I really didn’t think it was a big, pivotal move for the band. But it’s become part of pop culture here in the States.” Athletes use their music for motivation, sports teams play it in stadiums. And now, after ten years apart, the band are back together and touring.

As with Mother Mother and Slowdive, the result has been a new, younger audience. “When we ask, ‘Who has been to a Creed show before?,’ most people raise their hand. More than half the people buying tickets are under thirty-five-years-old.”

In the UK, there’s even a record label dedicated to giving artists a second chance. Cooking Vinyl began as a folk label in the 1980s, but in recent years has pivoted to scouring the market for undervalued acts — that is, ones who still have a fanbase, and maintain a database, but who have long since slipped out of fashion and become invisible to the major labels. Such as the York band Shed Seven, who had fifteen top-40 singles between 1994 and 2003, before being consigned to indie landfill. This year they had their first No. 1 album, on Cooking Vinyl.

‘In the 1990s, we took a lot of things for granted because success becomes normal. Now we soak it in’

Theirs was no TikTok-led success story — it was based on strategy. “We’re not lucky,” says their singer, Rick Witter. “We put in a lot of hard work. But it meant we were now a relevant band again, so we could start holding our heads up a little bit. I think the age side of things helps a lot, because we do things for us now. There’s no pressure from labels, and because we’re now self-managed, we control everything — even how much we’re going to spend on putting an amp in a van and getting it from A to B.”

While most bands who get second chances have seen the benefits primarily in streams and ticket sales, the Cooking Vinyl model depends on sales of physical product. These are not artists who have suddenly seized the imagination, so there isn’t going to be a surge: it’s more about bringing them back to everyone who ever liked them.

“We’re not obsessed with TikTok,” says Cooking Vinyl MD Rob Collins. “It’s more: how big is their email list? Can they sell tickets? When did they last tour? If an artist has a solid touring base, coupled with a great campaign, then you can sell physical product.”

What the artists get from their second chance varies. Obviously, there’s the validation of suddenly being adored. But for Guldemond, there was a new relationship to his music. “Those old songs really didn’t mean a lot then,” he says. “But now they have found their way into a whole other community, and accumulated substantial depth and ideas around identity, alienation and authenticity. This quirky, unviable music has given us our big break, and we take that seriously: it’s such a great symbol for having the right intention to make art in the first place.”

“I am so grateful,” Witter says. “In the 1990s, we took a lot of things for granted, because success becomes normal, and something that should just be happening. Now anything good is appreciated, and we soak it in, because you never know what might change.” Not that he’s gone overboard: after we finish chatting, he’s heading to the airport for a last-minute all-inclusive package to the Canaries. A No.1 album no longer buys a month in Mustique.

For Mark Tremonti, it’s wonderful — and a little bit complicated. As well as Creed, he has a solo project, he works with musicians from Frank Sinatra’s old band, and he is a member of the metal band Alter Bridge. “I have four different bands I actively tour and write with and at the end of this year I’m going to have to dive into all four at once — three of them touring and one recording. Still, better than sitting at home watching Friends repeats.”

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.