Just about everyone is for liberty, but we mean different things by it. Far-right libertarians want almost all constraints on their actions removed. They desire free markets, no unions, low taxes, free speech and the freedom to be very rich. The oppressed want freedom from tyranny: in extremis, they want to be free from jail and free to live without the threat of arbitrary arrest and torture. The moderately oppressed want more freedom than they have now, but within the context of a functioning democracy that is more equal, and more supportive, than the kind of society imagined by the right. They make a distinction between liberty and license (complete freedom) of the kind that results in the pike dining at leisure on the minnows. Some libertarians seem completely relaxed about fat pike and vulnerable minnows — perhaps because they see themselves as naturally at the top of the food chain, or, in the worst case, there by dint of their exceptional brilliance and hard work, rather than by a mixture of luck, inheritance and timing.

Quentin Skinner, one of our greatest intellectual historians, is interested in how the concept of liberty has changed over time. In particular, he wants us to reflect on the older Roman tradition of liberty, as independence from the arbitrary will of others. This is what he means by liberty as independence. It contrasts with the late-Enlightenment emphasis in liberal thought on the idea that liberty is best conceived as non-interference — as absence of constraint or coercion, described by Isaiah Berlin as negative liberty, or “freedom from.”

Two philosophical influences Skinner doesn’t mention are key to understanding his approach: Ludwig Wittgenstein and J.L. Austin. Wittgenstein because of his emphasis in his later work on language as use; Austin because he showed how we do things with words and don’t just use them to describe or report. In a celebrated example of Austin’s, the words “I name this ship Queen Elizabeth,” uttered in the right context by the right person, actually name the ship — you perform a speech act by this utterance.

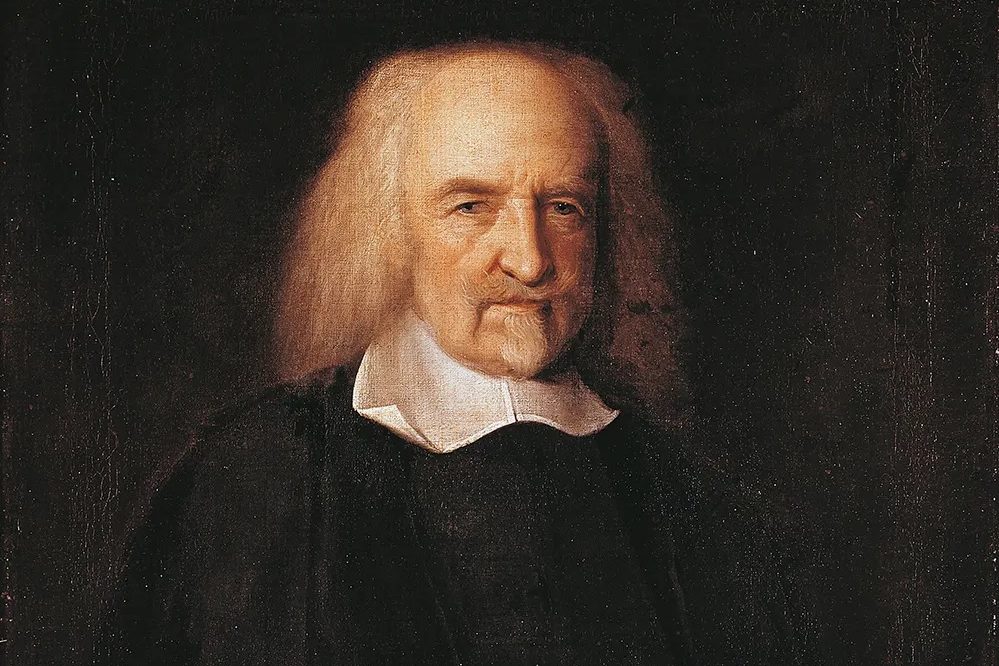

Throughout a long career (he is now 84, and he started very young), Skinner has explored how various political thinkers, including Niccolo Machiavelli and Thomas Hobbes, made interventions in ongoing debates and performed actions with their works; how their publications are, in an important sense, speech acts. He has demonstrated that an understanding of context is necessary to comprehend the wider impact of philosophical thought — one that can be at odds with the philosopher’s tendency to read such thinkers as if they were their own contemporaries rather than other people’s. Without understanding the minor thinkers these theorists were influenced by and responding to, the political events of their times, and the broader literary context, it is impossible to appreciate what they were doing by writing the words they did. They meant things by publishing their works, and such meanings are not accessible to the reader who ignores context. They didn’t always name their opponents, or signal to subsequent generations who they were attacking, but this would have been obvious to their first readers.

Liberty as Independence has a simple theme, signaled by the title and set out with admirable clarity in its introduction and conclusion. Skinner contrasts two historically important concepts of liberty. In the Enlightenment, and in particular in the last decades of the 18th century, the idea of liberty as absence of coercive constraint came to dominate and eventually eclipse an older tradition. Before that, Skinner shows, there was a rich history of freedom that in part stemmed from the works of Cicero and other Roman thinkers. This characterized liberty as independence, in the sense of the absence of arbitrary power over your life and body. The theme is straightforward — one that relates quite closely to Philip Pettit’s characterization of the republican ideal of liberty as non-domination (though Skinner takes care to explain how liberty as independence is a somewhat different concept).

The main chapters of the book are rich in detail and apt quotation, contextualizing major thinkers, such as Hobbes, Locke and Hume among their lesser-known contemporaries, and showing how much of what they wrote was a response to political events, including civil war and revolution. The rich context of ideas for Skinner also includes the novels of Henry Fielding and Samuel Richardson, which challenged over-confident Whig views of the smooth function of judicial administration in Britain.

This is an academic book, and its chapters are heavily footnoted. But Skinner is not just describing a historically important conceptual transformation, the details of which historians of ideas fight over in seminars. He is intervening in two ways. First, he wants to make the academic case that there actually was this change in how liberty came to be understood, and to explain some of the causes of this transformation. That is essentially a corrective debate about intellectual history — important, no doubt, though not for everyone.

But, as he makes clear in his conclusion, his is also a political intervention. He wants us to reflect on the nature of liberty, and recognize that the dominant view of it as absence of interference can obscure some instances of unfreedom today. He believes that the concept of liberty as independence has much to contribute to our debates about moral and political improvement.

He asks us, for example, to think about how de-unionized workers live at the whim of employers, and to consider how frequently women can still be so economically dependent on their male partners that they lack freedom in an important sense, even though they might, in terms of the no-constraint view of freedom, be considered free to choose to live otherwise.

Liberty as independence also connects with notions about democracy and acts as a counter to the idea that you could be freer under a benign dictator than under a system of government by the people. And, just as Donald Trump is signaling his intentions towards Panama and Greenland, Skinner makes the point that not just an individual’s but also a state’s autonomy to act can be undermined, even when there is not explicit coercion: “It is the mere awareness that the investing state or corporation has the power to impose its will that has the effect of taking away the liberty of the disadvantaged state.”

Leave a Reply