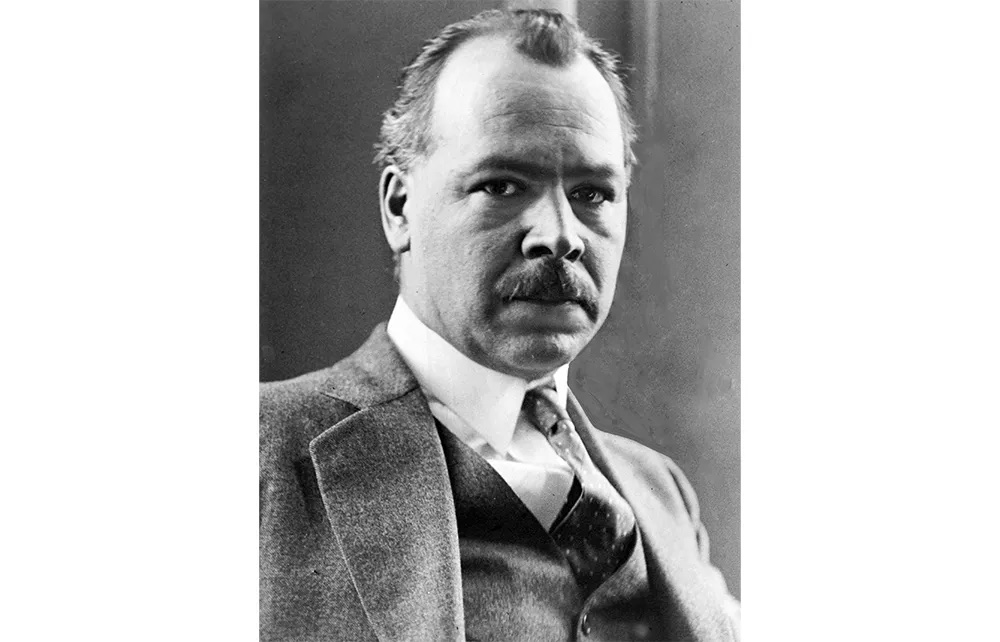

The idea was revolutionary — yet there was something ancient at its heart. The scientist Nikolai Vavilov, arriving in Petrograd in 1921 to take the helm of the Bureau of Applied Botany and Plant Breeding, was on a sacred mission: to make, in his words, “a treasury of all known crops and plants.” The world’s first seed bank would shape the future of agriculture — possibly even eliminate failed harvests and hunger. This was gleaming scientific idealism, but there was also an element of the Old Testament Ark about it.

The vision would collide with the brute reality of Stalin’s own efforts to bend nature to his will, and then the nightmarish Nazi invasion of Russia in 1941. Petrograd — by then named Leningrad — would be besieged for three years and transformed into a frozen necropolis with iced-over corpses lying in the streets.

The blockade of Leningrad was one of the most murderous in history. In the space of one terrible starvation winter — 1941-42 — it is reckoned that around one million citizens perished. Throughout this, Vavilov’s team of young botanists were undergoing their own extraordinary crisis. First they faced the task of preserving this world-leading seed bank against desperate, famished citizens foraging for any food — a siege within a siege. Then they needed to keep the institute functioning in the face of extreme cold (electricity could never be guaranteed and temperatures dropped to -40°F); to protect the seeds against German bombing raids and from the gnawing teeth of rats; and, most pressingly, for the botanists to find the superhuman strength not to consume the seeds themselves. Simon Parkin is excellent at evoking the city-wide torture of starvation — and the ingenuity in the institute’s quest to cultivate new food sources as the siege progressed.

Yet the bureau had already faced great peril before the Nazis. The effort to establish this seed repository — Vavilov was a dedicated explorer, who acquired specimens from countries around the world — in a revolutionary society should, on the face of it, have been a straightforward triumph for the new Soviet system. Pure science knew no borders and throughout the 1930s Vavilov had friends and admirers everywhere, especially in Britain. His pioneering work could have ensured intellectual and humanitarian garlands for Russia; but the aftershocks of revolution had brought ideological convulsions.

“The monster had tasted hot human blood,” as one Menshevik observed. Stalin’s distrust of intellectuals with middle class hinterlands and the catastrophic famines throughout Ukraine and other Soviet states in the 1930s (in part the result of his sociopathic pursuit of the Kulaks and push for collectivization) made the very idea of a seed bank a highly charged political issue. Vavilov also had a bitter rival — a “peasant agronomist” called Trofim Lysenko, who dismissed new theories of plant breeding, believing instead that “one simply had to train plants to meet one’s goals.” Lysenko’s background was more to Stalin’s taste, and so was his message at the time of the famines: that Russia’s crops could be improved instantly by pure Bolshevik intervention.

In November 1939, Vavilov was summoned by Stalin to Moscow. In a chilly audience, frighteningly conveyed by Parkin, the botanist tried to explain to his leader the aims of the institute and of his team. It was as if, Parkin writes, his words were “bouncing off a stone wall.” Vavilov was faced with Stalin’s war on truth: he was told his “impure” ideas were treachery. It was simply a matter of time before the NKVD operatives came for him. He was imprisoned and tortured repeatedly, his life compassed in wet cells as death approached. His young team continued his work, though terrified of suffering the same fate.

Other branches and vines are entwined in Parkin’s rich narrative. As Hitler launched Operation Barbarossa, there was a Nazi botanist called Heinz Brücher (aided by William Denton-Venables, an English prisoner of war with a passion for botany), who knew all about Vavilov’s project and was desperate to seize it for himself. The Nazis had their own version of eco-fanaticism: a vision of prairies and steppes shaped to Aryan tastes. And though the Germans never actually penetrated Leningrad itself, Brücher ensured that other Russian botanic institutes were looted, with some of Vavilov’s seeds in the haul. Then, in the grounds of an Austrian castle, he and his British assistant planted stolen strains of rye and wheat and barley, helped by concentration camp prisoners — horror and scientific absorption silently co-existing.

Parkin’s gripping, sensitive account is punctuated by violence and murder — Nazi and Stalinist alike — and underscored by the horror of the Leningrad siege. But the seeds, and those who tended them, become potent symbols of hope. In a landscape of unimaginable darkness, Leningrad’s custodians of future crops and flowers and fruit were mighty sentinels of life.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.

Leave a Reply