To no one’s surprise, the Tolkien: Maker of Middle-earth exhibition was a huge success when it opened last October at the Bodleian in Oxford, the library where J.R.R. spent so much of his time. Had tickets been on sale, Tolkein would have been be a sell-out, but the Bodleian had made it free. The visitors book was peppered with observations such as: ‘It made me cry with joy… sensationally splendid.’ There’s also a less hyperbolic view, in a childish hand: ‘It was interesting to see how he made The Hobbit and Lord of the Rings.’

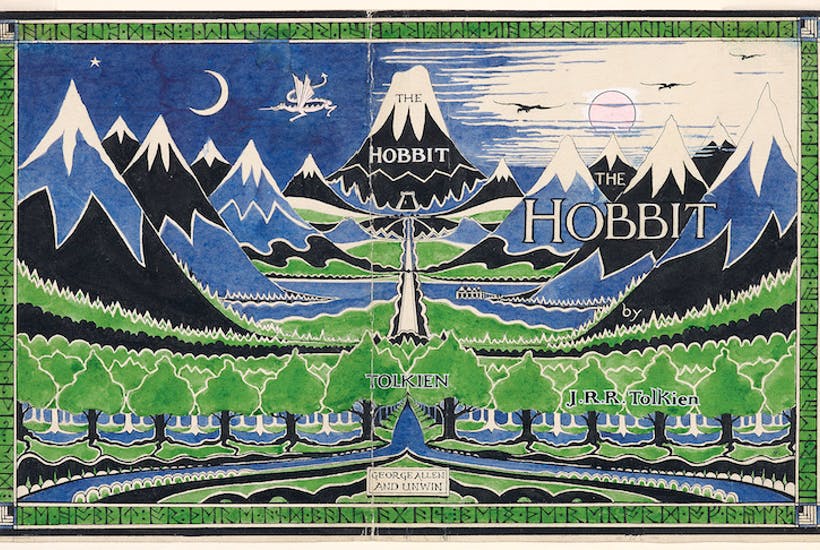

Tolkien, Maker of Middle-Earth is now at the Morgan Library, New York City. It is rather a small show, almost Hobbit-sized. This is a remarkable feat of compression on the part of the curators, the Bodleian’s Catherine McIlwaine and the Morgan’s John McQuillen, who have pared down 500 boxes of Tolkien holdings. In fact, the catalog of the exhibition, which McIlwaine edited and which contains contributions from other Tolkien scholars, is better than the show itself, with all the things she wanted to include in the show but couldn’t.

The centerpiece of the Oxford display was a replica of Tolkien’s study at his home in Oxford, with his pipe, his Windsor chair and his writing desk with green baize. I’m glad they got in the smoking. This was where his children, as well as his students, would come to see him. Famously, he chanced upon a blank page when he was marking School Certificate exams, and on it, out of nowhere, he wrote the opening sentence of The Hobbit: ‘In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit…’. The story was told to his children, and here are some of the charming Christmas cards and letters from Father Christmas that he wrote for them year after year, with splendid lettering and envelopes and a special stamp from the North Pole, and sketches for Roverandom, the dog story he made up for them. There’s also a forbidding Owlamoo to help his son Michael with his night terrors.

The Morgan does give us a peek into his home life, with a tiny, poignant letter to his father, dictated when he was four, which was never sent because his father died; a sketch of two young men by a hearth, one darning his trousers (‘What is home without a mother — or a wife?’), drawn when Tolkien was 12 and sent to his mother before her premature death from diabetes; a moving letter from one of his Exeter College friends who died in World War One. There’s a lovely sketch of his married life in the war. There’s a preposterous menu of ideas for discussion by the Inklings, the literary group he founded with C.S. Lewis and Charles Williams. All are glimpses of a man with a genius for friendship and a delight in his family. There’s nothing, however, about his deeply rooted Catholicism. But we do see his academic gown.

Most of the exhibition is about the works, not least his painstaking maps. Many of his paintings for the books are here. I am inclined to agree with Tolkien’s own view that ‘I never could draw’. And there are, too, a great many letters from Tolkien’s extraordinary range of admirers: W.H. Auden, Iris Murdoch, and C.S. Lewis, who rightly declared that The Lord of the Rings excels in ‘sheer sub-creation… as if from inexhaustible resources.’

What we get here, in short, are glimpses of the boundless creativity of J.R.R. Tolkien, not Peter Jackson, who made the films of the books by which most people know them. And, thank God, we don’t get a hint of the awfulness of poor Tolkien’s unintended legacy, which can roughly be summed up in the grim word ‘fantasy’ — games as well as rubbish children’s literature. We get the man and the writer. And that is enough.

This article was originally published in The Spectator magazine.