At one point during the part-concert film, part-documentary Hans Zimmer & Friends: Diamond in the Desert, super-producer Jerry Bruckheimer refers to Hans Zimmer as “the greatest living film composer in the world.” Zimmer, present when such flattery is offered, does not exactly nod in agreement, but nor does he laugh it off. While there are those who would argue that John Williams or Howard Shore have as great a claim to such a title – to say nothing of the equally influential Danny Elfman, Michael Giacchino or Alan Silvestri – there is one incontrovertible reply. Zimmer has a two-and-a-half hour movie dedicated to him and his work, showing in one-off engagements in theaters worldwide at the moment – and the rest of them don’t.

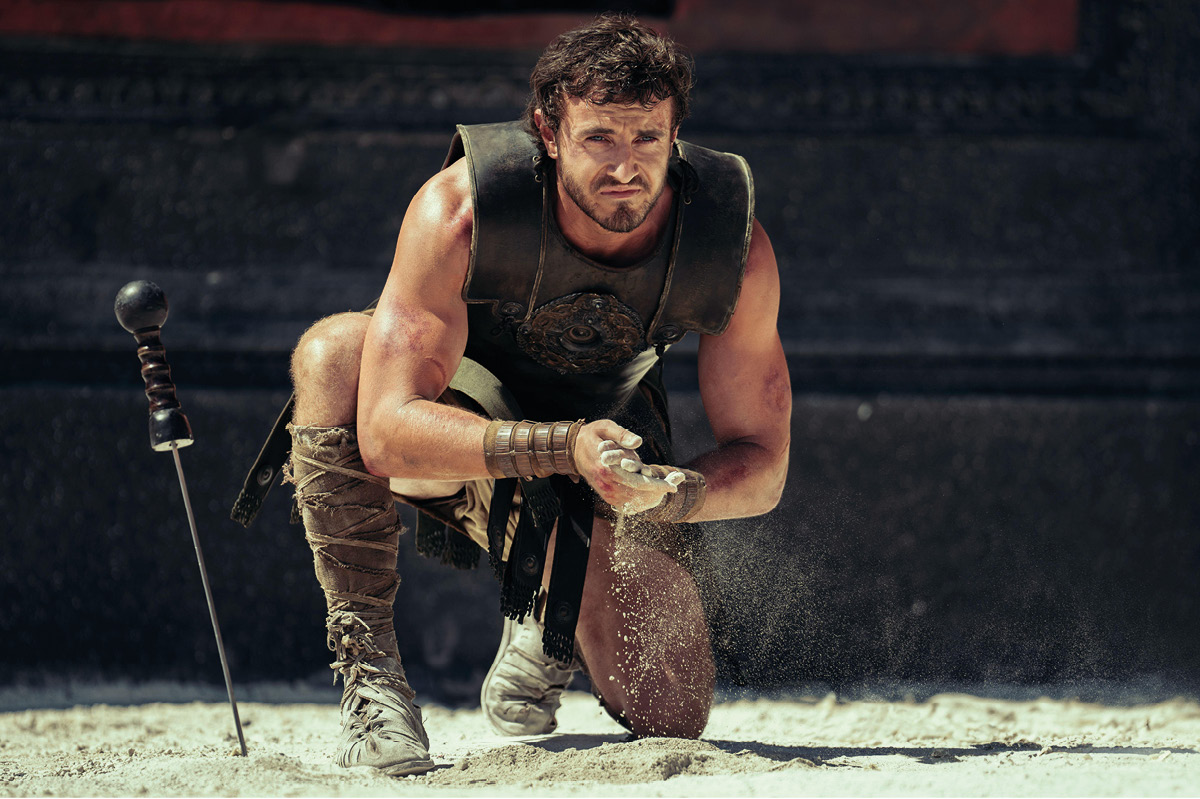

In truth, Zimmer has been a favorite of film aficionados for decades. He may have broken through with his Oscar-winning score to The Lion King, but it was his extraordinarily powerful, Grammy-winning music for Crimson Tide in 1995 that changed the face of mainstream film composition as we know it. Steering the requirements of blockbuster films away from the Holst and Wagner-aping grandeur of Williams and James Horner towards a more electronics-driven direction, heavy on wailing vocals, male voiced choirs, dramatic basslines and string ostinatos, Zimmer went on to score many of the most influential and beloved movies of the past three decades, including Gladiator, Pirates of the Caribbean, The Dark Knight, Inception and many, many more.

If he is less prolific today than he was a decade ago, it is because he has been engaged on an almost never-ending world tour since then, which began, almost tentatively, with a show at which I was present in London’s Hammersmith Apollo in 2014. Nobody really knew what to expect, but the show, entitled Hans Zimmer Revealed, gradually added layers of instrumentation and texture over its first few songs, as Zimmer’s ensemble gradually encompassed a full band, then an orchestra, and then eventually a full choir, offering a suitably all-encompassing wall-of-sound to bring his film scores to life. The presence of the Smiths’s Johnny Marr guesting on guitar was merely the icing on the cake.

Marr appears as an interviewee in Paul Dugdale’s film, offering typically wry and appreciative comments. He notes that Zimmer brought him and Pharrell Williams together, thus bridging the apparently enormous gap between the men who wrote, respectively, “Heaven Knows I’m Miserable Now” and “Happy.” He’s just one of a range of Zimmer appreciators offering incisive and often fascinating nuggets, from the youthful (Finneas and Billie Eilish, Zimmer’s collaborators on “No Time to Die” and Dune stars Timothée Chalamet and Zendaya) to the more seasoned. Inevitably, Christopher Nolan makes an appearance along with Bruckheimer and Marr, and Denis Villeneuve, who has supplanted Nolan as Zimmer’s go-to director, pops by for a suitably grateful cameo.

But most people will not be watching Hans Zimmer & Friends for A-list back-slapping. Instead, Dugdale’s great skill is to take an apparently tricky brief – how do you make a concert film where there’s no lead singer, and all the music is taken from films? – and execute it with enormous panache. Much of the on-stage footage, shot and edited to perfection, is genuinely thrilling; the peerless cellist Tina Guo, in particular, stands out, along with virtuoso guitarist Guthrie Govan, as they tear through most of Zimmer’s greatest hits. If one were to quibble, the sheer sturm und drang of the music performed becomes almost overwhelming before the end of the film. Only when they turn to the score for Interstellar do the crescendos and string-laden drama slacken somewhat, only to return in full glory for the performance of the heartbreaking “Stay” cue from that film.

Yet what lifts this a notch, and turns it from hugely enjoyable to unforgettable, is Dugdale’s decision to throw in some cinematic flourishes. The concert was filmed in Dubai, and the opening performance of one of the musical cues from Dune, shot from a helicopter in the desert, is breathtakingly ambitious. The visual delights keep on coming, whether it’s a suitably urban and paranoia-laden performance of the Dark Knight suite, complete with Zimmer playing with a bank of electronica in a skyscraper, or the breathtaking Interstellar music, performed in what seems to be a planetarium festooned with appropriately otherworldly stars. By the time that the show’s signature ending, “Time” from Inception, is performed with Zimmer playing a piano somehow mounted on the Burj Khalifa, with the camera panning outwards, it is impossible not to embrace the whole crazed, ambitious and thoroughly enjoyable affair. Like any diamond, this glitters and shines beyond compare.

Leave a Reply