Musicians cast a long cultural shadow. Politicians may wield considerable power in their time, but although today’s young people are still generally aware of John Lennon, they are less likely to have heard of the British prime minister Sir Alec Douglas-Home, despite the fact that he was running the country during the year the Beatles first came to international prominence. This is not the place to discuss the relative merits of writing ‘I Am the Walrus’ as against introducing the UK Resale Prices Bill (1964), but try offering T-shirts of both gentlemen on eBay today, and see which one sells.

While the recordings, compositions, images and even the signatures of certain deceased popular musicians can be monetized and marketed long after they have gone to join the great after-show party in the sky, managing and policing their legacies is a complex job, requiring teams of lawyers and other specialists. ‘The paradoxical compulsion at the very core of music estates,’ says Eamonn Forde in this entertaining and wide-ranging exploration of the subject, ‘is that they must keep the dead alive. At their very best, they defy science; at their very worst, they are Weekend at Bernie’s.’

As the English saying goes, ‘Where there’s a will, there’s relatives’. More than a few musicians have died leaving multiple potential beneficiaries, such as three or four ex-spouses and a veritable football team of children. Further confusion may be sown by a conflicting profusion of wills, as in the case of Aretha Franklin, or as with Prince and Bob Marley, no will at all. Lengthy court cases between interested parties are therefore very common, often sabotaging attempts to generate income from the assets in question.

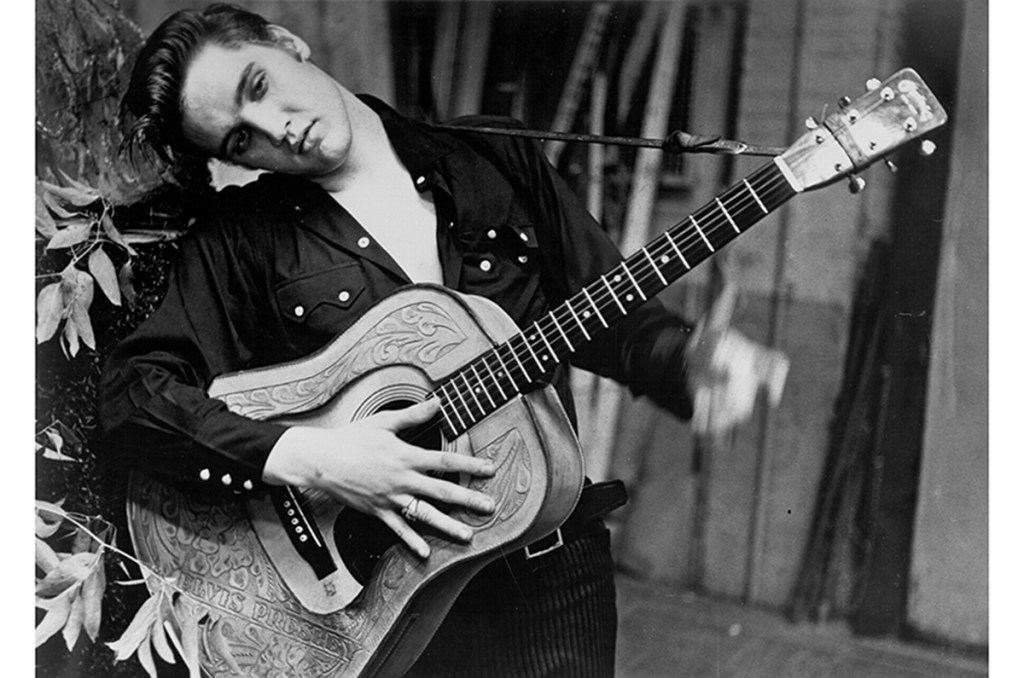

When Elvis finally left the building in 1977, the public reaction of his manager recalls that of the widow in The Importance of Being Earnest, whose hair ‘turned quite gold from grief’. Bragging that he had shed no tears, ‘Colonel’ Tom Parker told reporters that ‘it don’t mean a damned thing. It’s just like when he was away in the army’.Yet the way in which the Elvis estate gradually set about preserving and successfully monetizing his legacy since those days — especially once his former wife Priscilla eased out Parker and took control far more capably herself — set the benchmark for how most other deceased musicians’ estates have since conducted themselves.

The best examples featured here respect the artistic integrity of the musician and supply the needs of longtime fans with carefully packaged reissues. Forde is mistaken, however, in claiming that the demand for unissued tracks and alternate takes only developed in the late 1980s, following the advent of the CD, and that until then ‘old records were incredibly hard to get hold of’. Companies such as Charly, Ace and Bear Family embarked on wide-ranging reissue programs in the 1970s, and in the process made countless previously unissued recordings available. The major labels were slow to follow, but that is another story.

At the book’s core are the many perceptive interviews Forde has conducted with musicians’ relatives, such as Janie Hendrix (in charge of Jimi’s estate); attorneys, such as John Branca (who has represented Michael Jackson in life and in death) and specialist companies, such as Jam Inc (responsible for a range of deceased artists, including John Lee Hooker, Jim Morrison and Janis Joplin). Famous living musicians with an eye on their own legacies would be well-advised to pay close attention to these stories, both good and bad.

Indeed, estate management has many pitfalls, both in financial terms and in questions of taste and suitability. The genuine marketing items discussed here include Bob Marley-branded anti-COVID face masks with a design reading ‘Don’t Worry About a Thing’, official Miles Davis Montblanc pen sets, retailing from $600 to $4,500, and a range of Thelonious Monk-related products including ‘cups, hats, hoodies, iron-on patches, soap, T-shirts, tap handles, metal and neon signs, pins, playing cards, mouse pads, posters and food products’, knocked out by a company whose original remit had simply been to brew a Belgian-style beer called Brother Thelonious. All of which — to quote the response of one of Frank Zappa’s sons to a new method of exploiting his father’s legacy — might strike some as ‘a smörgåsbord of awesome’. Others may disagree.

The time-honored phrase ‘a former tour de force is forced to tour’ has been given new meaning with the advent of so-called ‘hologram’ technology, which has seen the likes of Buddy Holly treading the boards again, despite the minor drawback of having died in 1959. Some estate managers also express enthusiasm here for the new developments in voice simulation, which they hope will eventually enable their dead clients to sing songs or endorse products unknown to them when alive, accompanied presumably by the symphonic sound of barrels being scraped.

As Buddy might say, but this time in disgust: ‘Oh boy…’

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s November 2021 World edition.