Ethel Rosenberg was an exceptional woman. Born with a painful curvature of the spine to a poor family of Jewish immigrants and a mother who never loved her, she was determined to make her life matter. A talented singer, she won a place at New York’s prestigious Schola Cantorum and performed at Carnegie Hall. Having found clerical work, she helped organize strike action and then won a court vindication. Seeing the rise of fascism, she came to embrace the concept of communism, and when war arrived she campaigned for America’s entry.

Ethel’s exceptionalism did her no favors, however, in paranoid post-war America. Although she focused on her children, she was still far too close to her husband’s work. Already seen as ‘peculiar’, she was widely misjudged and easy to misrepresent. Aged just 37, in 1953 she said farewell to her two young sons and became the first woman in American history to be executed for a crime other than murder.

The Rosenberg case made international headlines in its day and has since inspired numerous novels, plays, histories and biographies. Anne Sebba’s riveting reappraisal not only includes previously unseen letters and testimony but also manages to extract Ethel from her marriage. Usually the lives and actions of ‘the Rosenbergs’ are presented as inextricably linked — even their Wikipedia entry is combined. Furthermore, this important and compelling book raises resonant issues around what happens when collective fear leads to hysteria and justice is willfully ignored.

Ethel married Julius Rosenberg in 1939. She remained grateful to him for enabling her to escape from her repressive mother, but she also loved him for his kindness, outlook and ambition. Neither saw any contradiction in being loyal American citizens while holding communist ideals. The USA was the land of the free, where people could choose their political beliefs, and in any case in 1941 the Soviets and Americans became allies.

As an engineer, a reserved occupation, Julius was posted to the Army Signals Corps laboratories, where research on guided missiles was undertaken. Ethel’s brother David was a technician at the Los Alamos atomic bomb development program. Both postings proved convenient when Julius was recruited as a Soviet spy. Ethel, however, had prioritized being a good mother over being a good communist. Not having had a role model, she plunged headfirst into the developing area of child psychology, subscribing to parenting magazines and seeking expert advice.

Julius and David were arrested in June 1950. The Cold War was ramping up, America was about to intervene in Korea and there was widespread public concern about the possibility of a communist nuclear strike. ‘Ethel’s tragedy was also America’s tragedy,’ Sebba writes, as Ethel became catastrophically entangled in some of the greatest political, social and economic issues of the age: America’s rapid descent from victorious nation into Cold War paranoia; the development and use of nuclear weapons; communism, anti-Semitism and misogyny.

Although devoted, Ethel’s lawyer provided only a patchy defense. The judge was biased and the prosecution deliberately exploited her to try to wring a confession from Julius. Even the jury had been carefully selected, with no Jewish representation, only one woman and no one who had expressed sympathy with communism or objections to the death penalty. The fact that Ethel was three years older than Julius meant she was cast as domineering, and her determination to appear unemotional and rely on the Fifth Amendment was taken as an indication that she had something to hide. The Jewish justices on the appeals committee were inundated with anti-Semitic hate mail, and the Rosenberg name alone was enough to associate Ethel and Julius with bolshevism in the public mind.

As this appalling story unfolds, the personal tragedy at its heart is never forgotten. After sentencing, Ethel and Julius were removed to separate cells beneath the courtroom. Ethel had sung throughout her incarceration, often accepting requests from fellow prisoners. Now she sang Puccini’s famous aria, in which Madame Butterfly yearns for the return of her beloved husband. She had refused to separate her fate from that of Julius, partly because she was fighting for justice but also because she loved her family and wanted to provide an example of dignity and courage.

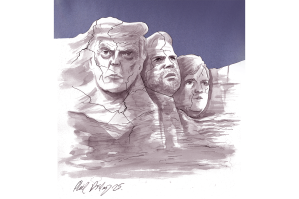

Ultimately, Sebba concludes, this is a story not just about innocence and guilt but also ‘the multiple meanings of betrayal’. Ethel’s mother had betrayed her by not cherishing her, endowing her daughter with lifelong loyalty to the man who did. Although it was not technically treason, Julius and David betrayed their country, and David later betrayed Ethel in the dock. Terrified of showing weakness at the height of the Cold War, the American state and legal system betrayed the ideals of American justice, and two presidents, Truman and Eisenhower, betrayed ‘their better selves’ by refusing clemency. Only Ethel betrayed no one.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.