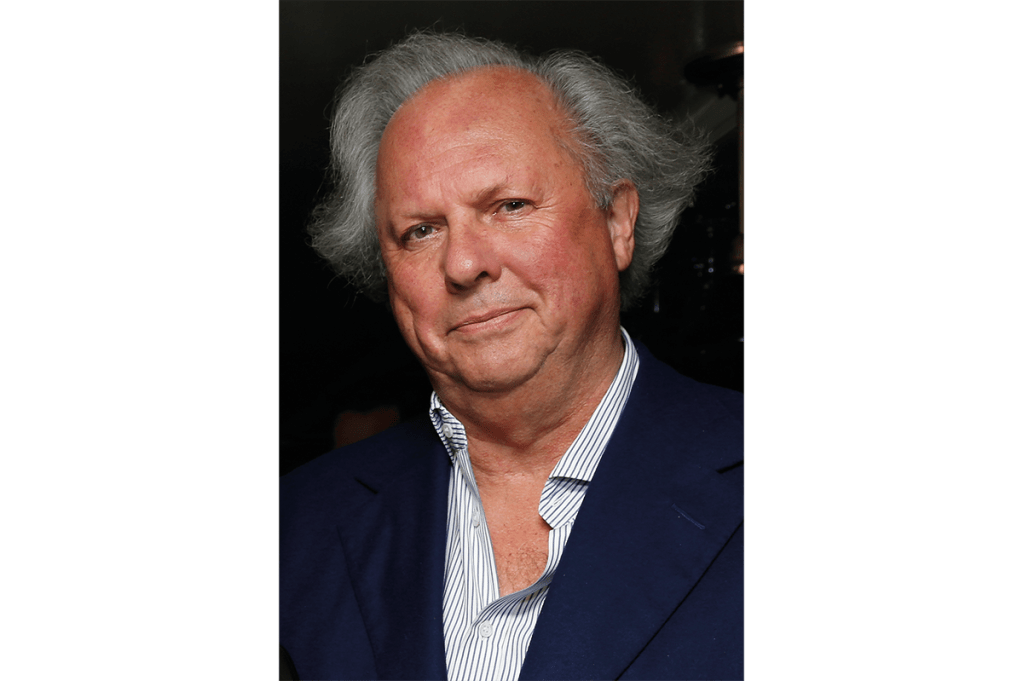

When I started working for Vanity Fair in 1995, I remember coming into the office one morning to discover that most of the senior editorial staff had disappeared. They weren’t at their desks and emails and phone calls went unreturned. Was this a Jewish holiday? Turned out it was the day Graydon Carter had set aside to write the “Editor’s Letter,” a monthly column at the beginning of the magazine signed by him but which he always asked one of his staff to write at the last minute. None of them wanted to be the poor schmuck saddled with the task.

The reason I bring this up is because the last book he “wrote,” a series of gripes about the George W. Bush administration, was a loosely stitched together collection of those letters. Which raises the question, what down-on-his-luck hack was roped in to ghost When the Going Was Good?

Below Graydon’s name on the title page are the words “with James Fox,” which sounds like the answer, but in the acknowledgments Graydon says “the writing is mine” and thanks James for “guiding me along the narrative path,” whatever that means.

He adds that he and James were “assisted” by someone called Hannah Lack, as well as a former colleague called Cullen Murphy: “He edited my copy when we were at Vanity Fair” – he wrote the “Editor’s Letter,” presumably – “and he edited this book.” He then thanks a fourth person – Ann Godoff, his editor at Penguin Random House – who gave the manuscript “a skilled and spirited edit and polish.”

A few pages into what Graydon calls “this slim volume,” I began to think the real author might be Craig Brown. It reads like one of Brown’s pastiches in the back of the British satirical magazine Private Eye, stretched to 432 pages. Take this passage, in which the celebrated magazine editor describes a dinner the day after he announced his departure from Vanity Fair in September 2017:

We also had a long-planned dinner the next evening with Sherry Lansing and Billy Friedkin along with Candy Bergen and her husband, Marshall Rose. Sherry couldn’t get over the fact that the story of my stepping down from the magazine was on the front page of that morning’s [London] Times. “Graydon, dictators get the front page when they step down!” Many days I look back on her statement and take it as a compliment.

That series of name drops, followed by a humblebrag, is typical of the man I knew in the mid-1990s, and I congratulate the four-person ghostwriting team for having captured him so well. Or perhaps it really is his own work. I know Fox isn’t the literary journalist he once was, but could he really bring himself to write a series of sentences like these?

When traveling on business, I stayed at the Connaught in London, the Ritz in Paris, the Hotel du Cap in the South of France, and the Beverly Hills Hotel or the Bel-Air in Los Angeles. Suites, room service, drivers in each city. For European trips, I flew the Concorde. I took round-trip flights on it at least three times a year for almost a decade. That’s something like sixty flights. My passport picture was taken by Annie Leibovitz!

To be fair to Graydon, this is a passage about the extravagant lifestyle enjoyed by glossy magazine editors in the 25-year period he was at Vanity Fair (1992-2017). Some of the details really are jaw-dropping. Attending his first Annie Leibovitz cover shoot, he learns that the food budget for her and her staff for that one day was more money than he’d spent producing an entire issue of Spy, the satirical magazine he co-founded in 1986.

Vanity Fair’s stable of writers are paid the kind of money investment bankers earn today – Dominick Dunne was on half a million dollars a year – and Graydon not only spiked one in five submissions, but he paid full whack for the articles he rejected. “I never paid a kill fee,” he says. Graydon doesn’t disclose how much he was earning when he stepped down, only that when Si Newhouse, the billionaire owner of Condé Nast, offered him a starting salary of $300,000 to come and work for him in 1992, he told him to double it.

One of the perks of working for Si, he reveals, is that he offered his editors interest-free loans and Graydon appears to have taken full advantage of this. He boasts of owning properties in New York, Connecticut, the South of France and London, not to mention a restaurant, a “fleet” of classic cars and an airplane.

All this bragging gets quite tiresome and makes the reader wonder why Graydon still feels the need to try and impress the reader with what a big cheese he is. Aren’t 60 trips on Concorde enough to allay his status anxiety? But he is that familiar figure from the memoirs of successful New Yorkers – an alpha male with paper-thin skin, which may remind you of someone.

If the book can be said to have a villain, it’s Donald Trump, whom Graydon famously dubbed the “short-fingered vulgarian” back in the 1980s – a not-so-subtle reference to his penis size – and he constantly ridicules the President for trying to rebut this allegation.

Yet to anyone who’s worked for Graydon, the skewering of Trump for his myriad insecurities feels a lot like projection. During my stint as a Vanity Fair editor, I recall one hapless intern finding himself sharing an elevator with the boss and, because he couldn’t think of anything better to say, remarked that he hadn’t seen him around the office much lately. Graydon scowled at him, then, a few days later, dispatched one of his trusted lieutenants, Aimée Bell, to have a word with the chump. “You don’t tell one of the hardest-working editors at Condé Nast that you haven’t seen him around the office much lately,” she scolded.

One of Graydon’s saving graces – the thing that made him fun to have a drink with – was how full he was of malicious gossip about his rivals, the flipside of constantly bigging himself up. I remember him gleefully relaying the story of Tina Brown, his predecessor at Vanity Fair, being asked to show a documentary television crew round the offices for a segment on 60 Minutes, the prestigious CBS news program, and getting completely lost within seconds. “In eight years of working there, she’d only ever gone from reception to her office,” he said.

But with the exception of Trump, almost the entire cast of boldface names in When the Going Was Good are showered with praise. Every time he mentions meeting some Hollywood legend, he goes on to say what great friends they’ve become – unless they’re dead, in which case he tells you about his starring role at their funeral (pallbearer, eulogy-giver, etc). You need to go pretty far down the celebrity food chain to find someone he’s prepared to gossip about. In 25 years, the only guests to misbehave at the Vanity Fair Oscar party, according to Graydon, have been Paris Hilton, Harvey Weinstein and George Lazenby. Whatever the opposite of a tell-all memoir is, this is it.

In a rare moment of self-deprecation, Graydon quotes Henry Porter, the one-time London editor of Vanity Fair, suggesting he call his autobiography Magna Carter: How to be More Like Me, which would be a better title for this book. There’s a compilation of Pooteresque advice in the final chapter – “Always carry a handkerchief” – but there’s scarcely a page that doesn’t contain some pearl of wisdom, often directed at would-be magazine editors. Which is odd, considering the book reads like an extended lament for the golden age of magazines, with Graydon convinced we’ll never see their like again.

The lesson I learned from him during my two-and-a-half years at Vanity Fair is that dealing with the rich and famous on a daily basis is a “pride-swallowing siege” (as Jerry Maguire would have it), unless you are as egotistical as they. Indeed, behaving like a sacred monster is often the only way to earn their respect.

Perhaps that’s why Newhouse showered his top editors with so much gold, knowing that the only way to entice people like Tom Cruise and Demi Moore to pose for his magazine covers was to create some stars of his own and send them out to seduce the rich and famous.

In Graydon, he found his Norma Desmond – the subtext of this book reminded me of her famous line in the 1950 film Sunset Boulevard: “I am big. It’s the pictures that got small.”

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s May 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply