Romain Rolland once complained that ‘there is too much music in Germany.’ Today there are too many television critics in the world. Some of the finest writers of multiple generations spend most of their writing lives recapping last night’s television. Is any of it really criticism, or are thousands of words agonizing over, say, Don Draper, adding up to anything more than the digital equivalent of chip wrapping?

Such thoughts do not bother the critics. They are convinced of their rectitude, secure in their sense of being the most powerful tastemakers in the land. As the New Yorker’s queen of TV Emily Nussbaum put it in 2015: ‘Those of us who love TV have won the war. The best scripted shows are regarded as significant art – debated, revered, denounced.’

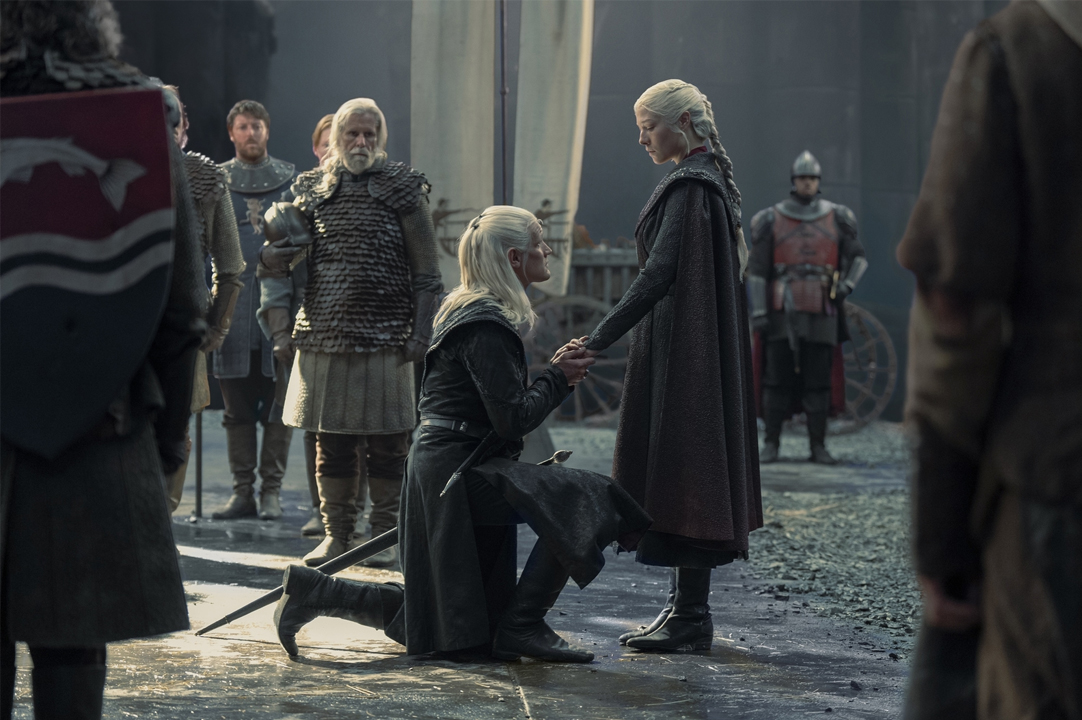

Last night it was Game of Thrones’s turn to be denounced. Now Götterdämmerung-ing its way towards a finale after eight seasons, yesterday’s episode, The Long Night’, had been built up for months – years even – as the greatest spectacle yet seen on television.

And in a sense it was. The army of the dead reached Winterfell, cascading over its living defenders, a tidal wave of rotten limbs, blue eyeballs and rusty swords. Three dragons dueled above them. Heroes fell in battle; heroes were made in battle. There was futility, sacrifice and gallons of blood: blood sluicing down faces, blood exploding out of stomachs and mouths, sleets of blood and bone falling like rain. It was Game of Thrones. It was immensely entertaining and about as intellectually demanding as watching two dogs scrap over roadkill.

With weary reluctance and epic stoicism I waded through the critical response. They were not very pleased. Everything was wrong. Here was Alyssa Rosenberg in The Washington Post:

‘“The Long Night” left me with grave doubts that [Game of Thrones] can stick its landing with the visual and moral integrity it has grasped for, and at times, attained….’

Visual and moral integrity? Are we talking about the Rose Window in Durham Cathedral? Rosenberg goes on:

‘One of the more interesting aspects of the series has been its relationship to ideas of empowerment for women.’

Under discussion: a television show where a dragon fights an army of zombies. There’s more:

‘I love Game of Thrones; more than any other work of art, George R.R. Martin’s novels and the television adaptation of them have defined my career as a critic… If you asked me whether Game of Thrones is a genuinely great show, after “The Long Night,” I’d have to answer: not today.’

Imagine living in a world where Mrs Dalloway and Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon exist and thinking that Game of Thrones (which is entertaining, don’t get me wrong) is a work of art. Then imagine making a career out of typing up little takes about it. And then imagine this defining your career as a critic!

Critics who only write about shallow subjects will only produce shallow writing. How television became the most critically examined art form of our century remains a baffling mystery. Christian Lorentzen has made a good stab of understanding why critics enjoy it so much though:

‘Enjoying television, once something considered slothful, became a respectable activity among the chattering classes, and one could hear a sigh of relief. It was the sound of the meritocracy letting itself off the intellectual hook.’